An Irish Exhibit at The Art Institute Of Chicago

After celebrating the Chicago Blackhawks win, amidst the sea of black and red jerseys from the victory parade, I ventured beyond the beloved, iconic lions at the Art Institute of Chicago and back in time, to the exhibit, “Ireland: Crossroads of Art and Design, 1690-1840.” Here, it was my shirt that stood out for its color, with its shamrock green connecting me not to a sports team, but to the country of my ancestors. The woman behind the welcome desk smiled broadly, praising its hue, and my choice to wear it as a nod to the exhibit. I have to admit I was happy she noticed – Irish pride, I guess.

The shirt I wore to the Ireland exhibit.

It is a gift from my sister Stephanie who is co-author of this blog. (This was not featured in the exhibit. It comes from my closet. Ha Ha)!

But the choice of shoes I wore was ill-advised. You should always wear sneakers to an exhibit, especially when you’ll be on your feet for hours, gawking at priceless artifacts. Think long-distance standing. My sandals were ill-equipped to traverse 150 years of beautiful paintings, silver, ceramics, linens, needlepoint, mahogany furniture, etc from the 18th century. More than 300 objects were on display. Still, my curiosity carried me onward as the exhibit focused not only on the person portrayed in the artwork, but on the artist’s life as well. My only other struggle was balancing awkwardly between taking snapshots on my handy portable electronic device (without flash mind you…I wouldn’t want to be responsible for causing an emerald green to fade or making a bronze bust blink.) and my audio guide. Neither are cumbersome at all, the audio guide is like a walkie-talkie with a strap that you slip around your wrist. But trying to get a good shot of a mahogany card table with faces or “masks” carved into it with a battery that is running low. while also holding the audio up to your ear and trying to listen closely isn’t easy. In the silver section, a fellow museum-goer’s iPhone, or whichever make or model she had for taking photos, clattered to the floor, but there was no damage, except that she seemed slightly embarrassed. “Don’t be,” I felt like telling her. “I’m surprised I haven’t dropped something yet.”

Visitors could be forgiven for being distracted though, especially when the entrance to the exhibit was so striking. The first objects I noticed were a large silver cup, the head of a mounted elk with awe-inspiring antlers, a harp and a romantic painting of a half-clothed woman with the aforementioned musical instrument. While taking in the sights, I was further immersed in this new world, with the Irish music that was lilting through the air.

Samuel Walker. Irish, active 1731-69. Two-Handled Cup and Cover. About 1761-66… Silver. Dublin” This cup was “made from the Great Seal of Ireland from the reign of George II for Lord Chancellor John Bowes,” according to the museum label at the exhibit. ” The Merriam-Webster online dictionary writes that a “Great Seal,’ is a large seal that constitutes an emblem of sovereignty and is used especially for the authentication of important documents.”

According to the exhibit, “Living approximately 400,000 to 7,700 years ago (11,000-8,000 B.C), the now-extinct Giant Deer or ‘Irish Elk’ (Megaloceros giganteus) once inhabited many parts of Europe, Asia, and North Africa, but some of the best-preserved remains have been found in peat bogs in Ireland. Symbols of welcome, antlers were displayed in the entrance halls of Irish country houses and symbolized a family’s long historical connection to the land (although such histories were sometimes embellished or fabricated). This skull and antlers was rediscovered in the 1870s in a bog in Ballybetagh, about nine miles south of Dublin. In 1921, the Royal College of Surgeons in Dublin elected to send the antlers as a gift to a sister organization, the American College of Surgeons, based here in Chicago.” As a Chicagoan, all I can say is, “What a gift!” What did the fair inhabitants of my city send in return? It seems like there’s more to this story.

John Kelly. 1734,( Irish, active 1726-1734). Willow, brass. The harp is called cláirseach in Ireland and is a national symbol. It was the instrument of the ancient Celtic bards or traveling musicians. Later, it became a political symbol of the Irish rebels during the 1798 uprising. Today, the harp’s image is on the coins of the Republic of Ireland, according the exhibit.

“Portrait of a Lady as Hibernia,” by Robert Fagan. About 1801. Oil on canvas. Fagan is Irish, born England, active in Italy, 1761-1816. According to the label, “Robert Fagan was born in London , but he spent most of his artistic career in Italy. This painting is Fagan’s response to the 1800 Act of Union, which abolished the Parliament in Dublin. It depicts a woman as Hibernia, the personification of Ireland. She wears emerald-green drapery with gold shamrocks, an Irish wolfhound at her side. One of Hibernia’s hands rests on a harp with broken strings, symbolizing the loss of Ireland’s independence, while the other holds a scroll inscribed with the phrase ‘Erin go bragh,’ (Ireland forever), probably the first use of Gaelic text in a work of ‘high art.”

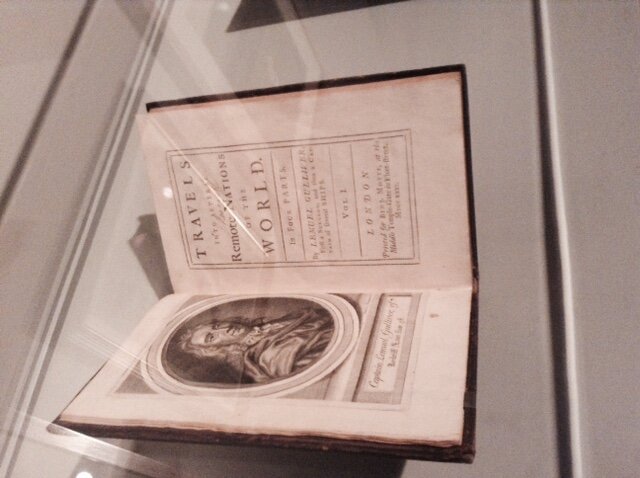

I was excited to see a 1st edition of Jonathan Swift’s “Gulliver’s Travels,” as it is well known, although I haven’t read it yet. Stephanie read it and she told me she enjoyed it. I wonder who first owned this copy, displayed now behind protective glass.

“1st ‘A’ edition,” 1726 of “Gulliver’s Travels” (London, printed for Benjamin Mott. Ink on paper. bound in brown calf with gold tooling on spine) by Jonathan Swift (1667-1745) on loan from the Newberry Library, another great Chicago institution. According to the exhibit,”Jonathan Swift, perhaps best known as the author of the satirical ‘Gulliver’s Travels,’ was born in Dublin in 1667. After a number of formative years spent in England, he became Dean of Saint Patrick’s Cathedral in 1713. Deeply concerned with the strength of Ireland’s economy, he became a staunch promoter of Irish-made goods….”

The next section of the exhibit I visited was titled “Portraiture.” Most of the portraits were of royalty and the upper classes. Some were of children and the artists themselves. I wonder what it would be like to pose for a portrait. What would the artist reveal? According to the label on the wall, “Although an artist’s ability to capture an individual likeness was highly prized, a portrait was also a visual statement of wealth, power and status.” It seems that no matter the time period, we are always trying to promote ourselves through a visual medium, the latest example being the much-maligned “selfie.” Portraiture was also the way to mark events in one’s life and remember the dead.

Portrait of Sir Neil O’Neill, 2nd Baronet of Killyleagh,1680. Oil on canvas. by John Michael Wright , English, 1617-1694. According to the exhibit,”Sir Neil O’Neill, 2nd Baronet of Killyleagh, was a member of the ancient O’Neill family, Gaelic chieftains in the north of Ireland. In this portrait, designed to convey power and authority on the stage of war, O’Neill is surrounded by an attendant , a faithful Irish wolfhound, and curiously, 15th-century Japanese armor. It is possible that the armor refers to the persecution of Jesuits in Japan; both O’Neill and the artist, John Michael Wright (a religious exile from England), were staunchly Catholic. O’Neill would lose his life at the Battle of Boyne, ten years after this portrait was painted.”

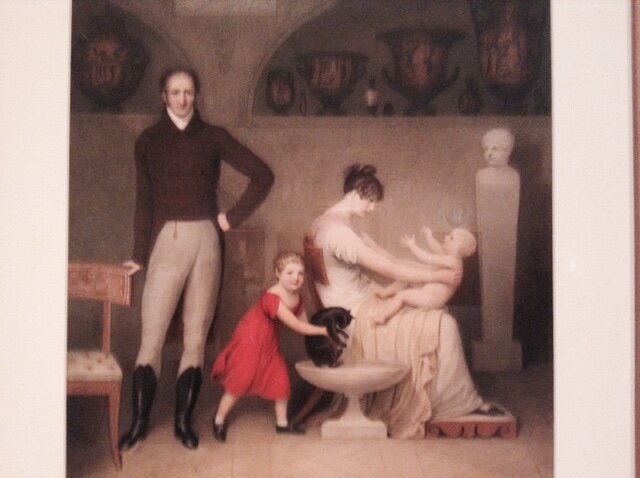

So, Sir Neil O’Neill only lived a decade more after having that portrait painted. Yet, here I am, viewing his likeness in 2015. I also enjoyed the portraits of families and children, particularly the two pictured below. The first painting, “The Artist and His Family” seems like such a happy scene with the little girl holding her cat and the mother holding her baby, who is the picture of health. I sent a postcard of this to my parents. The other painting, “Portrait of John William Peters, the Artist’s Son,” struck me because of handsome young John’s soulful gaze. He is not posing with toys, but rather a book, which he clutches close to his chest, in much the same way he seems to keep his thoughts to himself. He reveals only that he is an obedient son, posing for his artist-father. What did they talk about, while his Dad painted, I wonder. Was there a reward for John in sitting still for so long and what did the young boy think of his portrait upon completion?

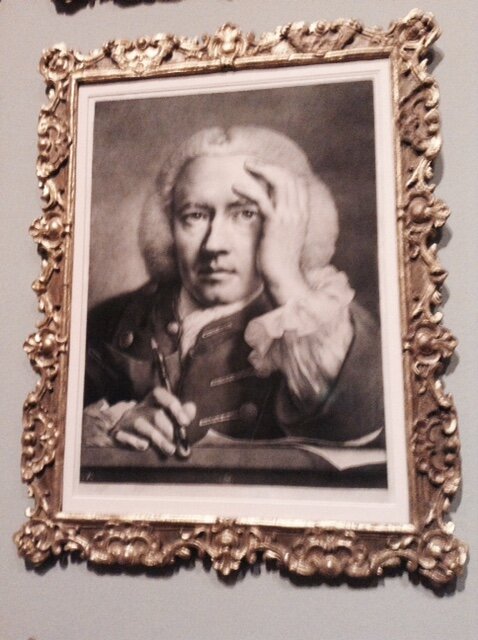

Some of the other portraits used mezzotints, which according to Dictionary.com is, “a method of engraving on copper or steel by burnishing or scraping away a uniformly roughened surface.” An artist named Thomas Frye, an Irishman who was active in England from 1710-1762, used this method to create “fancy’ or ‘fantasy’ heads, – idealized, theatrical, or character studies meant to demonstrate the artist’s skill and versatility in representing a variety of poses and expressions,” according the the museum label. There was a whole wall of these “fancy” heads, looking me over as I gazed at them, probably thinking that I had neither necklace nor adornment in my hair and was therefore not fancy enough for their liking.

Thomas Frye. Eighteen Life-Sized “Fancy Heads” 1760-62. Mezzotint on paper, gilt-pressed paper frames. The original “Fancy” heads were too delicate to travel so the frames are replicas. However, one has the original frame, and that is the “self-portrait of the artist”, featured in the middle row, third from the right, looking at the museum goer, holding one hand to his brow and a crayon in the other hand, as if contemplating how he is going to sketch you, a bizarre 21st century subject.

The next portrait I was captivated by was one of a blacksmith, for two reasons. The first was the connection, written about on the museum’s label, between the arduous profession and Irish myth. “Blacksmiths held a special place in Irish folklore; it was believed they knew spells to cure various diseases and that the iron they handled warded off evil.” If this is true, I could use a good blacksmith. The second reason, I found the oil on canvas painting interesting was because it was simply titled “The Blacksmith.” While I know, for example, Sir Neil O’Neill, 2nd Baronet of Killyleagh’s identity, I will never know the farrier’s (someone who shoes horses) name, beyond who he worked for. He deserves his place in history, especially given all the multitasking his job required and the hard work of people like him. They also forged Ireland’s story, with their sweat and determination. Stephanie recently discovered that one of our ancestors was a farrier.

“The Blacksmith,” Oil on canvas. 1800/50 by Robert Richard Scanlan, Irish, active 1826-76. The exhibit says, “He [Scanlan] had a particular fondness for all aspects of equine life, representing hunters, horse traders, carriages, and stables. Here he depicted the blacksmith believed to have shod the horse Copenhagen for Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, before the Battle of Waterloo in 1815.”

Besides the paintings, there were also sculptures of interesting people. One of the forebears of the Bank of Ireland, for example, seemed like an august personage, while also having an approachable air about him. If only I had thought to ask him for a loan, considering all the stunning silver I saw later in the exhibit. He was, however, my introduction to the arts, as an esteemed patron.

“David La Touche II” 1750/75. Marble. By Jan (John) van Nost the Younger, Flemish, active in England and Ireland. about 1727-87. “Of Flemish origin, the sculptor Jan van Nost the Younger was the principal marble sculptor in Dublin during the second half of the 18th century. This bust of David la Touche II, a prominent Irish banker of Huguenot (French Protestant) descent, demonstrates the cosmopolitan nature of Irish art patronage. The La Touche family established the first commercial banking venture in Dublin and were highly regarded for their civic-mindedness. The bank they founded later became the Bank of Ireland, which still exists today.’

Dublin was a prosperous city, full of artistic talent. There was the Smock Alley Theatre and the Crow Street Theatre. There was Italian opera and comedies. According to the exhibit, “The world premiere of Handel’s Messiah took place at the Great Music Hall in Fishamble Street in 1742, after the composer was invited to perform a series of concerts in Dublin by the Duke of Devonshire, then lord lieutenant of Ireland.” Stephanie and I try to do something cultural once a month, and we would have snapped up those tickets. We also would have wanted to see the works of playwrights Oliver Goldsmith and Richard Brinsley Sheridan, as they are famous writers from this time, according to the exhibit.

In Belfast, there was even a literary society, which was actually more of a theatrical society called The Adelphi Club. It seemed like a bit of an all-boys club, so Steph and I wouldn’t have been able to join. On second thought, perhaps we would have with some cross-dressing, inspired by the women who dress as men in Shakespeare’s plays.

“The Adelphi Club, Belfast,” 1783, Oil on canvas. by Joseph Wilson, Irish, active 1766-89, died 1793. “The Adelphi Club was a literary society active in Belfast in the 1780s, and its membership largely consisted of people associated with theater. The fourth figure from the left here is Amyas Griffith, a colorful writer and central figure of the association. The silver tankard Griffith holds is undoubtedly one presented to him by the brewers of Belfast in 1782. The painter has included himself on the far right of the composition, holding a palette and maulstick (a tool used to steady an artist’s hand while painting).”

Artists depicted not only scenes from their own lives, but also the great works they admired. This was especially true of Shakespeare's plays. I would have to say it was at this point that I was especially glad I paid the extra five dollars (as a member) for the audio guide. I enjoyed hearing some of the most famous lines from Macbeth, Act 5, Scene 5 recited by a gifted orator.

I have to re-read this play. I think I would understand the beauty and the power of its words much more than I did as a teenager. I’d have a better grasp of its tragedy too.

“To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow,Creeps in this petty pace from day to dayTo the last syllable of recorded time,And all our yesterdays have lighted foolsThe way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor playerThat struts and frets his hour upon the stageAnd then is heard no more: it is a taleTold by an idiot, full of sound and fury,Signifying nothing.

”

“Macbeth Consulting the Vision of the Armed Head,” 1793. Oil on Canvas. by Henry Fuseli, Swiss, Active, 1741-1825. “After the success of John Boydell’s Shakespeare Gallery in London – an effort to encourage history painting through the exhibition of paintings and prints of scenes from Shakespeare’s plays – James Woodmason opened his own Shakespeare Gallery in Dublin in 1793. He commissioned paintings from Irish and foreign artists, including this scene from ‘Macbeth’ by the Swiss artist Henry Fuseli. Woodmason’s exhibition was short-lived due to lack of interest, though his gallery was later used by Irish rebels as a clandestine meeting space.”

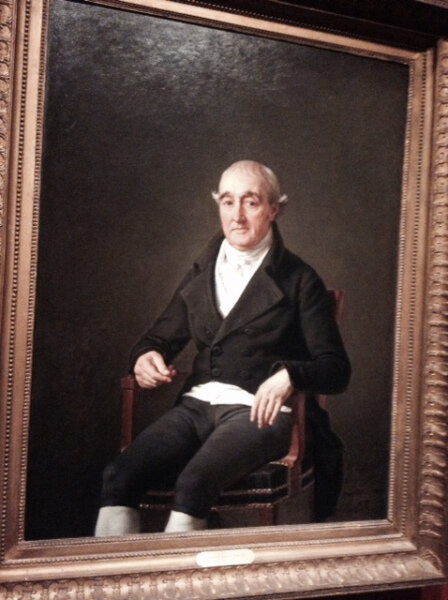

As Shakespeare so eloquently and brutally wrote, our lives are fleeting. Places such as the renowned Art Institute of Chicago are able to hold onto some of the echo and color of human beings who have long ago departed this world, through their artistic expression, which is both unique to their time and transcends ours. We have a window, a slim ray of light, into their concerns and how they wanted the world to view them. Cooper Penrose, for example, was a successful Irish lumber merchant and a Quaker. He wanted an image of himself that displayed his stature as a well-respected businessman and art collector, as well as a devout man of faith. As I read the museum’s label, I pondered the duality of these identities and how we are all still trying to reconcile our different beliefs and interests.

“Cooper Penrose” by Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748-1825), 1802. Oil on canvas. From the exhibit, “This portrait of an Irish lumber merchant and glass factory owner from Cork was painted by Jacques-Louis David, the leading painter of the French Neoclassical movement. The work is a testament to the sympathetic relationship between the Irish and the French. Painted during a brief window of peace during the long wars between Britain and France, this somber portrait reflects Penrose’s Quaker religion. As a collector of contemporary art, Penrose was sometimes at odds with his fellow Quakers; his deliberately modest appearance in this portrait served as a way to publicly affirm his faith.”

Much like the Quaker, Irish and French influences that were a part of Mr. Penrose’s life, the capital city of Dublin was multicultural as well. I was especially fascinated to read about Dublin’s early history as I hope to visit there some day. According to the exhibit, “Dublin made a convenient headquarters for successive invaders of Ireland. First, in the ninth century, came the Danes; the Normans arrived from England and Wales three centuries later. The settlement, located on the east coast, was readily accessible by sea.” Dublin began to resemble European cities. “By the 17th century, Dublin had acquired some of the attributes of a European capital and was the home of the English king’s representative, usually given the title lord lieutenant, who resided in Dublin Castle for part of every second year. A center of cultural and political life, Dublin Castle was also the city’s armory and the site of investiture [a ceremony conferring rank] for the Knights of the Order of Saint Patrick.” According to the official website of the British Monarchy, “Founded in 1783, the Order of St Patrick was historically used to reward those in high office in Ireland and Irish peers who supported the government of the day.” Examples of their distinctive ornamentation are in the photo below.

“Star of the Order of Saint Patrick,” About 1815.Rundell, Bridge and Rundell. (English, 1797-1843) Silver and enamel. “Badge of the Grand Master of the Order of Saint Patrick,” About 1850. Ireland. Gold and enamel. “The Most Illustrious Order of Saint Patrick is the Irish order of chivalry created by George III in 1783. Two examples of the order’s regalia, an eight-pointed star and the badge of the Grand Master of the Order, are on view here. Both incorporate shamrocks, the sky blue color of the knights’ robes, and the order’s Latin motto, ‘Quis separabit,’ derived from Romans 8:35 (‘who will separate us from the love of Christ’). The Grand Master’s badge also includes a harp surmounted by a crown.”

I thought the photo, see below, of Dublin Castle, was a happy picture of British officers and people from the town socializing at a grand, festive occasion at Dublin Castle. The dresses of the women are so lovely. However, the well-informed voice speaking to me through my audio guide called the artist’s point of view, “naive.”

Below is a view of the library at Trinity College in Dublin, (along with the head of real life museum-visitor). According to Trinity College Dublin’s website, the esteemed school was created in 1592 by royal charter. “The idea of a university college for Ireland emerged at a time when the English state was strengthening its control over the kingdom and when Dublin was beginning to function as a capital city.”

The next painting I took a photo of is inspiring because it fits into my romantic idea of the city as a place of great architecture and natural beauty. It is called, in part, “The Four Courts,” because it is the “bastion of law in Ireland,” according to the Courts Service. “The imposing entrance door leads into the great Round Hall and the original Four Courts of Chancery, Exchequer, Kings Bench and Common Pleas. Today these courts are numbered Court 1, Court 2, Court 3 and Court 4.”

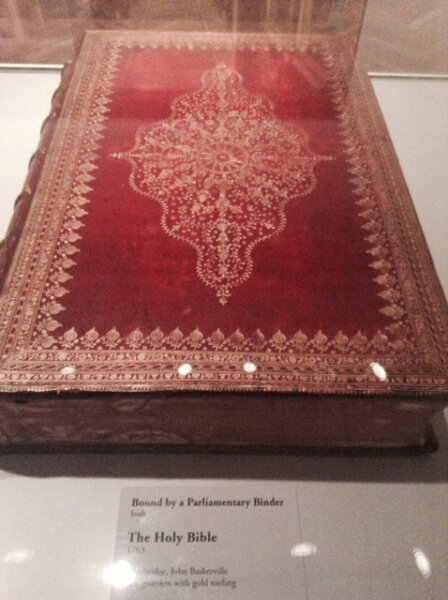

Another part of the exhibit that I enjoyed was “Bookbindings.” I read the label that introduced me to the room, after taking a brief glance around. “Perhaps less well known than other objects of Irish manufacture such as glass or linen, fine Irish bookbinding tooled in gold are among the highest achievements of Irish craftsmanship in the 18th century.” It’s as if the writer read my mind. I had never thought about this as an Irish skill, although I know the Irish are well-respected as writers. The books that were on display were tooled in gold, which was so beautiful and resplendent. The book as an object is in itself can be a work of art and I would say that’s more than true of these volumes. The label went on to say, “Prior to about 1750, Irish bindings resembled those produced in England and France. By the end of the century, however, largely as a result of patronage by Trinity College, the Irish Parliament, and wealthy individuals, Dublin bookbinders had developed their own techniques with leather and gold that in complexity and skill rivaled and in many cases surpassed bookbindings made anywhere else in the world,”

“The Holy Bible,” Bound by a Parliamentary Binder, Irish, 1763, John Baskerville. Goatskin and Gold Tooling. According to the placard about Bookbindings, “Perhaps the most elaborate and technically ambitious Dublin bindings were those commissioned by the Irish Parliament for the 149 manuscript journals of the Houses of Lords and Commons. The volumes were tragically destroyed in 1922, but by consulting rubbings taken in 1890, individual tools used on the parliamentary journals have been identified in surviving Irish bindings, including the binding of John Baskerville’s 1763 edition of the Bible included in this gallery. The border of this binding was made using an ‘insect roll,’ which impressed tiny image of crickets, bees, and other bugs into the goatskin.”

I wondered what it would feel like to hold that Bible in my hands. How heavy would it be? What would the text on the inside look like? There was an accompanying video showing how artists made reproductions of the Irish Parliamentary Bindings that were lost in a fire. It seemed like such an intricate process, with many different, very specific tools. How do you practice an art like that? Speaking of Parliament, I was also impressed by a “mace” I saw on display. A mace according to the Merriam-Webster online dictionary is “an ornamental staff borne as a symbol of authority before a public official (as a magistrate) or a legislative body.” I’ll have to admit it seems to me it could also fit another definition of mace; a heavy club used as a weapon. The one in the photo below, however, is an eye-catching silver.

The Art Institute also featured a bust (see the photo below) of one of the most famous faces of the Irish Parliament. His name is Henry Grattan, I will remember his name as someone to read about more.

“Henry Grattan” by Peter Turnerelli, (Irish, 1774-1839).1820, Marble. “Henry Grattan (1746-1820) was a member of the Irish Parliament who devoted his career to the cause of Irish independence. In this bust by Turnerelli, an Irish-born sculptor of Italian descent, the combination of unpretentious naturalism and classical drapery is appropriate for Grattan, whose eloquence was likened to that of the great orators of ancient Greece.”

Besides busts, I also saw some lovely ceramics. In the 19th Century, Ireland mostly imported ceramics and decorated them because they couldn’t compete with Wedgwood from Staffordshire, England, according to the exhibit. There were, however, ceramics factories that opened, the first being in Belfast. The most productive one was World’s End Pottery in Dublin. It was founded by the Irish Parliament and the Dublin Society, “which was dedicated to improving the country’s arts and manufacturing.” Henry Delamain was the most significant director of World’s End Pottery. “His experience as a sea captain in foreign armies and as a tea and porcelain importer made the pottery an international effort; in addition to Irish potters, he also employed craftspeople from abroad.”

The next photo of a ceramic that I took was of an Epergne or Sweetmeat Dish. I thought it was the most curious-looking object and I wasn’t sure what sweetmeats were so it was a double mystery. It looked so exotic and yet refined, with its many tiers. Was it a predecessor of the servers we see today at tea parties, I wondered. Would a vegetarian eat a sweetmeat? After the exhibit I looked up “epergne” online and according to Merriam-Webster it is “an often ornate tiered centerpiece consisting typically of a frame of wrought metal (as silver or gold) bearing dishes, vases, or candle holders or a combination of these.” The definition for “sweetmeat” is “a piece of candy or a piece of fruit covered with sugar.” According to the audio, the sweetmeat dish provided the perfect means to show off luxurious and tantalizing treats; a sign of privilege. I’m sure I would have been the rude guest who kept sneaking a candy from its lovely blue and white perches, while others mingled.

The next section I’m going to write about is the silverware, which was my favorite. It was beautiful. It gleamed. It was elegant as a shoe buckle or a sword. It seemed to capture the dazzling shimmer of the Irish soul. According to the exhibit, imported goods such as chocolate, tobacco, tea and coffee created a demand for new types of metalwork. Because of King Louis XIV’s discrimination against Protestant Huguenots in France, many of them came to Ireland. During the 18th Century, they constituted about 2 percent of the population in Dublin, but made up 20 percent of the silversmiths. That was one of the key things I learned on this trip to the museum – how international the influences in Ireland were, both in terms of wealthy Irish citizens traveling abroad on Grand Tours of Europe, and in terms of artists from abroad coming to Ireland to practice their craft. One of the speakers on my audio guide complained that people just think of Ireland in terms of Catholic versus Protestant. They don’t realize how multicultural the country is, especially Dublin, going back to the 1690s.

I appreciated the care the Huguenots took with their silver. I photographed a few examples of the craftsmanship of the silversmiths of Ireland. I chose objects that we still use in modern life and ones that are from a bygone era, which were intriguing.

The first item I will focus on is a scroll salt. If you’re scratching your head and wondering what that is, thinking to yourself “I know the word ‘scroll’ and the word ‘salt,’ but together they’re a bit perplexing,” then you’re in luck because the label explained it as follows. “The scroll salt is among the earliest known examples of Irish domestic (made for home, rather that religious use) silver. The scrolled brackets – to keep hot dishes off the tabletop and elevate the food’s presentation – and spool-shaped form were in keeping with the latest London fashion and may well have served as a model for similarly shaped dish rings in the late 17th century in both England and Ireland. In the course of the 18th century, they became almost exclusively an Irish form.” Stephanie could use a scroll salt to show off the Irish dishes she makes for this blog. I’ll suggest it.

The next items were sleeve cups and a toaster, which does not look like the one on your kitchen counter. It looks more like a shovel. There was also a lovely teapot I could imagine a family using when company came over.

There was also a reading lamp, which I found interesting because it had two candle holders. I was thinking, “Yes, of course this is what a lamp would look like in the 1700s.” No electricity. No cord. I wonder if the lamp was in a study or a library. What did the lamp’s users read?

The next items I photographed were the wall fountain and cistern. Can you imagine having a silver water fountain? So lavish! According to the exhibit, “A wall fountain and cistern en suite were the ultimate example of conspicuous consumption. In 1727, the 19th Earl of Kildare turned to one of Dublin’s leading silversmiths, Thomas Sutton, for the cistern exhibited here. Having exhausted his funds over such extravagances, the 19th Earl left the commissioning of the wall fountain to his son James, the 20th Earl of Kildare (later the 1st Duke of Leinster). For the fountain, the 20th Earl again turned to a Dublin silversmith, Robert Calderwood. While the cistern was primarily intended for cooling bottles of wine in cracked ice, it might also have served as a basin for rinsing glasses, with the water provided by the fountain.”

Wine Cistern. 1727. Thomas Sutton. Irish, active 1717-45. Commissioned by Robert FitzGerald, 19th Earl of Kildare, and Mary, daughter of William, 3rd Earl of Inquichin, Dublin, Silver. Wall Fountain. 1754. Robert Calderwood. Irish. active 1726-66. Possibly commissioned by James FitzGerald, 20th Earl of Kildare. Dublin. Silver.

The next museum piece was a monteith. A monteith, according to Merriam-Webster is, “a large silver punch bowl with scalloped rim.” The one featured below was created by one of Dublin’s most highly regarded silversmiths, Thomas Bolton.

The next silver objects that caught my attention were the shoe buckles and the cake/bread basket. If I had silver buckles on my feet I would dance a jig all the time. If I had a beautiful silver basket, I would bake delectable baked goods and bring them to my friends, while wearing my shoes with silver buckles.

The next object I photographed because it was such a large silver piece. Those whose job it was to polish and maintain the precious metal did not have an easy task. Their arms must have gotten quite a work out.

The next part of the exhibit I toured was the linen and textiles section. Flax according to the MacMillan Dictionary online is, “a plant with small blue flowers that is grown for the fibers in its stem and the oil in its seeds. The fibers from the stem of a flax plant are used for making linen (a strong cloth).” Flax grows especially well in Ireland’s climate. I had no idea it was so laborious to make linen from flax. To me, it is proof that the Irish are hard workers. According to the exhibit,”Entire families were involved in planting and harvesting the flax, while other tasks were divided along gender lines: women and girls spun the flax into yarn, and men wove the yarn into cloth.” It was also the one part of the textile industry that the English left alone because they liked linen so much. “Anxious to avoid competition from Irish textile manufacturers, at the close of the 17th Century the English Parliament enacted laws that severely curtailed the export of Irish woolens. The production of linen, however, was encouraged, and by the mid-18th century Irish linens were widely exported to the Continent and North America.” (Glass was also an import to the United States in the early 19th Century. Glass that was inscribed to celebrate Americans’ newly won independence from Britain was popular).

Needlework and embroidery were also practiced in Ireland during this time. They were important crafts for women of all classes. I would have been in a lot of trouble because I don’t have the patience and the works on display at the exhibit were lovely and impressive and must have taken a lot of patience and skill. Below is an example of a dress. I wonder who wore it and where she went in it.

Women also expressed their artistic side. Their “polite accomplishments,” included ” music, dancing, and drawing as well as painting with watercolor and making collages with shells, paper, feathers and pressed flowers.” Most women who enjoyed these activities, however, were from the upper classes, Women needed time and education for such pursuits. Mary Delany was a creative force who influenced many female artists. She had a special “paper-collage technique”. Below is an example of a collage that could bring cheer to a home and was not too costly. I liked the artwork because it reminded me of spring.

Artist Unknown. Irish. Study of a Grouse. Study of a Sparrow. 1797/1800. Watercolor, feathers, and paper collage elements on paper. “This pair of bird pictures are in their original gilt wood frames, which bear their maker’s label – Patrick Burke of 53 Grafton Street, Dublin. Burke worked at that address from 1797 to 1800, a fact that helps date these anonymous collages.”

In the music section there were a variety of interesting instruments, but my battery was running low so I only took a photo of the gorgeous green harp. I was so intrigued by it that I apparently leaned in too close and a sensor went off. The woman standing next to me asked the guard if the alarm had gone off for her or me, as she had apparently been drawn to the enchanting instrument herself. The guard said, “Her'” nodding in my direction while smiling sweetly. It was a gentle reminder not to get too close, but I was still the culprit. I guess I should have been embarrassed but at this point my feet were hurting so badly and I was deeply curious about this stringed instrument, one of the most well-known symbols of Ireland. This particular harp was displayed in promotional material for the exhibit so it had been of interest to me for a while. I stepped back a little, but I kept my focus on the harp as if it would suddenly play of its own accord.

“John Egan. Irish, active about 1801-41. Portable Harp. About 1820. Maple, spruce, ivory, catgut, and green paint with gilt decoration.” “Advertising himself as ‘Portable Harp Maker to the King,’ John Egan introduced a modern version of the ancient Irish harp, often, as in this example, painted green and decorated with gold shamrocks. Lightweight and strung with catgut rather than wire, Egan’s portable harps combine the traditional Celtic form with the rounded sound boxes of the fashionable pedal harps of his own time. The harps’ smaller size – offering greater portability and ease of use – contributed to a reawakening of interest in harp music in Ireland in the 19th century.”

After viewing the musical instruments, I ventured into the furniture section, which had a lot of beautiful wood with interesting, if somewhat intimidating carved masks. For that reason, it was unlike any furniture I’d seen before. According to the exhibit, that was in keeping with the Irish tastes of the time. “Perhaps the most striking aspect of Irish furniture is its creative and profuse decorative detail. Surfaces are often highly ornamental with low-relief carving, particularly on table aprons, while table and chair legs are supported by squared hairy-paw feet. The Irish particularly favored the classical deities Bacchus [the Greek god of wine], Venus [the Roman goddess of love and beauty], and Zeus [the king of the gods in Green mythology] , who often make an appearance through carvings of the symbols that are typically used to represent them: lion or satyr [‘lustful, drunken woodland gods,’ according to Google’s dictionary] masks, shells, and eagles, respectively.” So, if you bump into the edge of a table, expect it to roar back at you. What I also learned is that the city of Cork played an important role in the craft of high-end furniture making. “The city of Cork, for example, was the first port of call for ships from the New World destined for the British Isles; as a result Irish cabinet- and chair-makers had the first opportunity to select the finest Caribbean mahogany.” Below is a photo of a cellarette, which I photographed because I thought it was so distinctive.How many people today have one of these? I also wasn’t sure what a cellarette was until I read the label. (I have to learn more about wine). I liked the dramatic lion heads.

“Probably Mack, Williams and Gibton, Irish, 1811-1829, After a design attributed to Francis Johnston, Irish, 1760-1829. Cellarette. 1821/25. Dublin. Mahogany with metal liner. In the second half of the 18th century, open wine cisterns were replaced by covered wine coolers, or cellarettes, which were believed to keep wine cold for a longer period of time. This example is based on Roman sarcophagi and has been given expressive form by the Dublin architect Francis Johnston, inspired by a plate in Thomas Sheraton’s “Cabinet Dictionary” (1803). The cellarette has richly carved ornamentation – including a bunch of grapes and the heads of four lions, representing Bacchus. It most likely belonged to a member of the highly selective Order of Saint Patrick, founded in 1783 to keep titled Irish Protestants loyal to the king: that society’s emblem was a star-shaped badge of Saint Patrick flanking a crowned harp on its front, as seen here.”

Another interesting piece of furniture was this card table made out of Caribbean mahogany. Right away I noticed the intricate carvings and the feet of the table, which are paws. I could only imagine the wild, raucous games played at this table. It seems like something Max would bring back from his travels in “Where The Wild Things Are,” if he got into the import business.

Maker unknown. Mahogany. circa 1740.”One of a pair, this card table is an excellent summation of Irish furniture design,” according to the label. “Starting with the use of dark, densely grained Caribbean mahogany. The carver has provided a shaped apron with a central lion mask for Bacchus, carved tassels much favored by Irish carvers, and flanking legs that incorporate satyr-like masks, also in keeping with the Bacchic theme. Acanthus (flowering plant) carving continues down the cabriole legs [a curved furniture leg ending in an ornamental foot, according to Merriam Webster], which terminate in characteristically Irish squared hairy-paw feet, with a pronounced acanthus carving directly above inspired by a horse’s fetlock, the tuft of hair on the back of a horse’s leg above the hoof.”

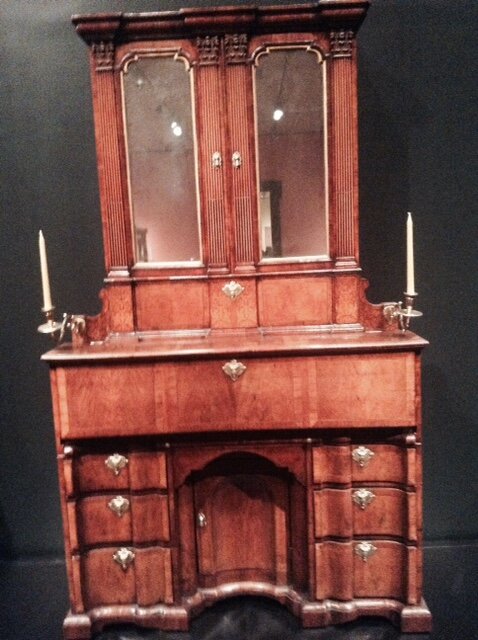

The next piece of furniture I looked at was a desk and bookcase. The desk had candles, which is striking to me because it reminds me that this is all from a long time ago. I can imagine writing in the dark by candlelight, though. It sounds a bit romantic. I also have so many books. I would love a beautiful bookcase.

“John Kirkhoffer. Irish, born Germany, active 1730s. Desk and Bookcase. 1732. Dublin. Walnut, holly, mirror glass, and brass. When this walnut desk and bookcase was purchased by the Art Institute of Chicago in 1957, it was described by the dealer as “English about 1710.” Only recently have the name of the maker and date, ‘John Kirkhoffer Facit [sic] 1732’ been found inscribed in pencil on the bottom of the lower right drawer. As the oldest known piece of signed and dated Irish furniture, it has become a Rosetta stone for attributing other closely related examples of Dublin cabinetry, especially those notable for their use of similar marquetry inlay.” According to Merriam-Webster “marquetry” is “a decorative work in which elaborate patterns are formed by the insertion of pieces of material (as wood, shell, or ivory) into a wood veneer that is then applied to a surface (as of a piece of furniture.” Note: The bookcase is not crooked, It’s just my photo.

There were so many fascinating objects on display. I've only touched upon a few, even in the sections I've written about. My battery died in the furniture room, but there were beautiful artistic depictions of the bond between the Irish and their horses and a whole other section about the places in Ireland where people enjoyed nature, such as Giant's Causeway. I would also like to visit there some day. It was a phenomenal exhibit. The last object I will write about is a small crucifix that caught my attention because it looked so humble, a simple souvenir of yew wood. Both the artist who created it and the person who owned it are unknown, yet it is a moving representation of belief, carried on a journey.,

“Crucifix. 1776. Lough Derg, County Donegal. Yew wood. This crucifix is one of thousands made as souvenirs for pilgrims to the site of Saint Patrick’s purgatory at Lough Derg in County Donegal. The crucifix is carved with symbols of the Passion and inscribed with the date ‘1776,’ the year of the owner’s pilgrimage. It has long been assumed that the arms of these crosses were made short so they could be easily hidden in a time when open Catholic worship was forbidden; in fact it is more likely they were short to avoid breakage.”

![“The Blacksmith,” Oil on canvas. 1800/50 by Robert Richard Scanlan, Irish, active 1826-76. The exhibit says, “He [Scanlan] had a particular fondness for all aspects of equine life, representing hunters, horse traders, carriages, and stables. Here he…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e1a79c4d343ec0c523e8728/1583287787928-W5YUBBO862OPRZ2N5FA6/ireland-blacksmith.jpg)