The Book Of Kells - The Neverending Story

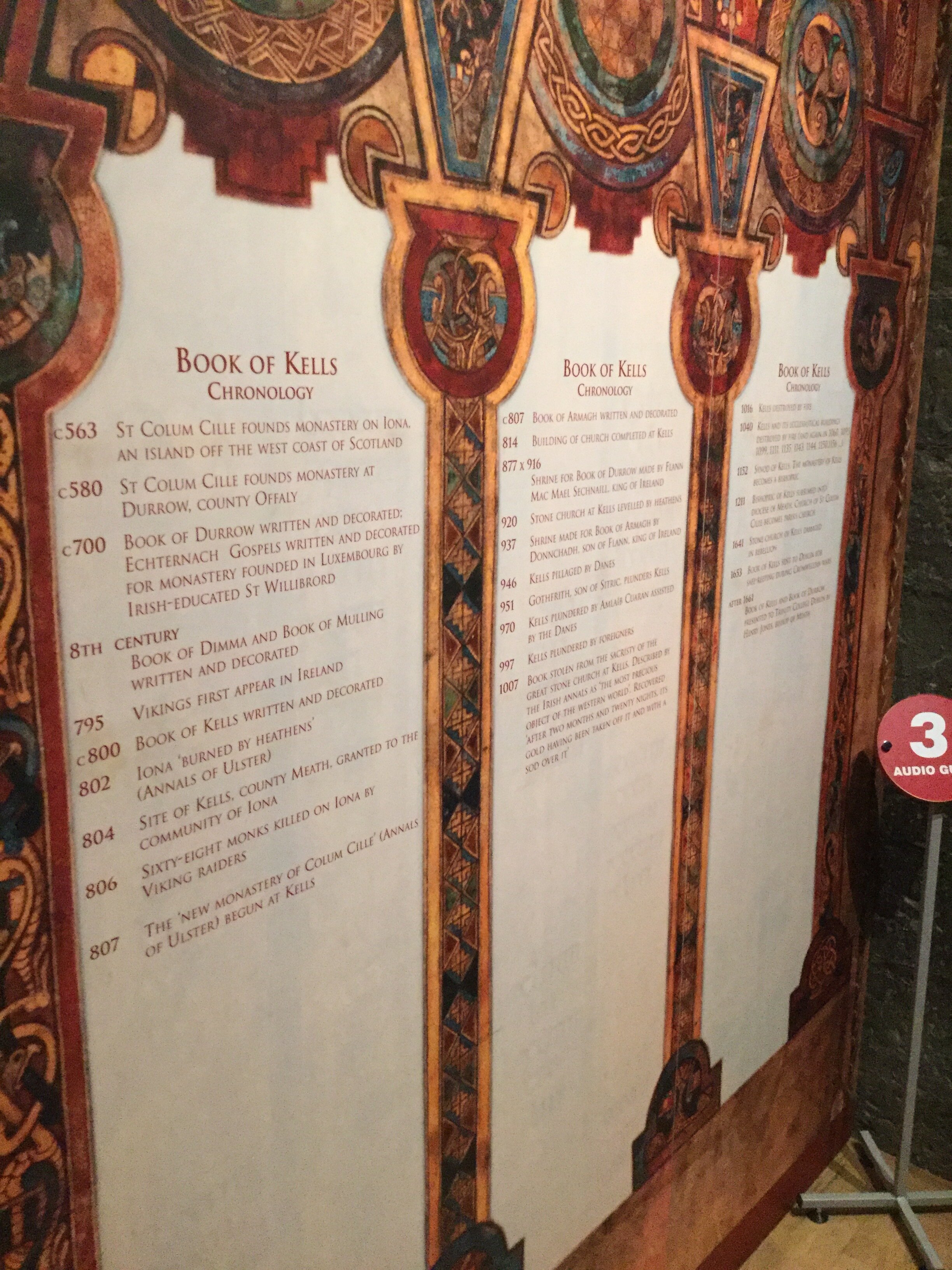

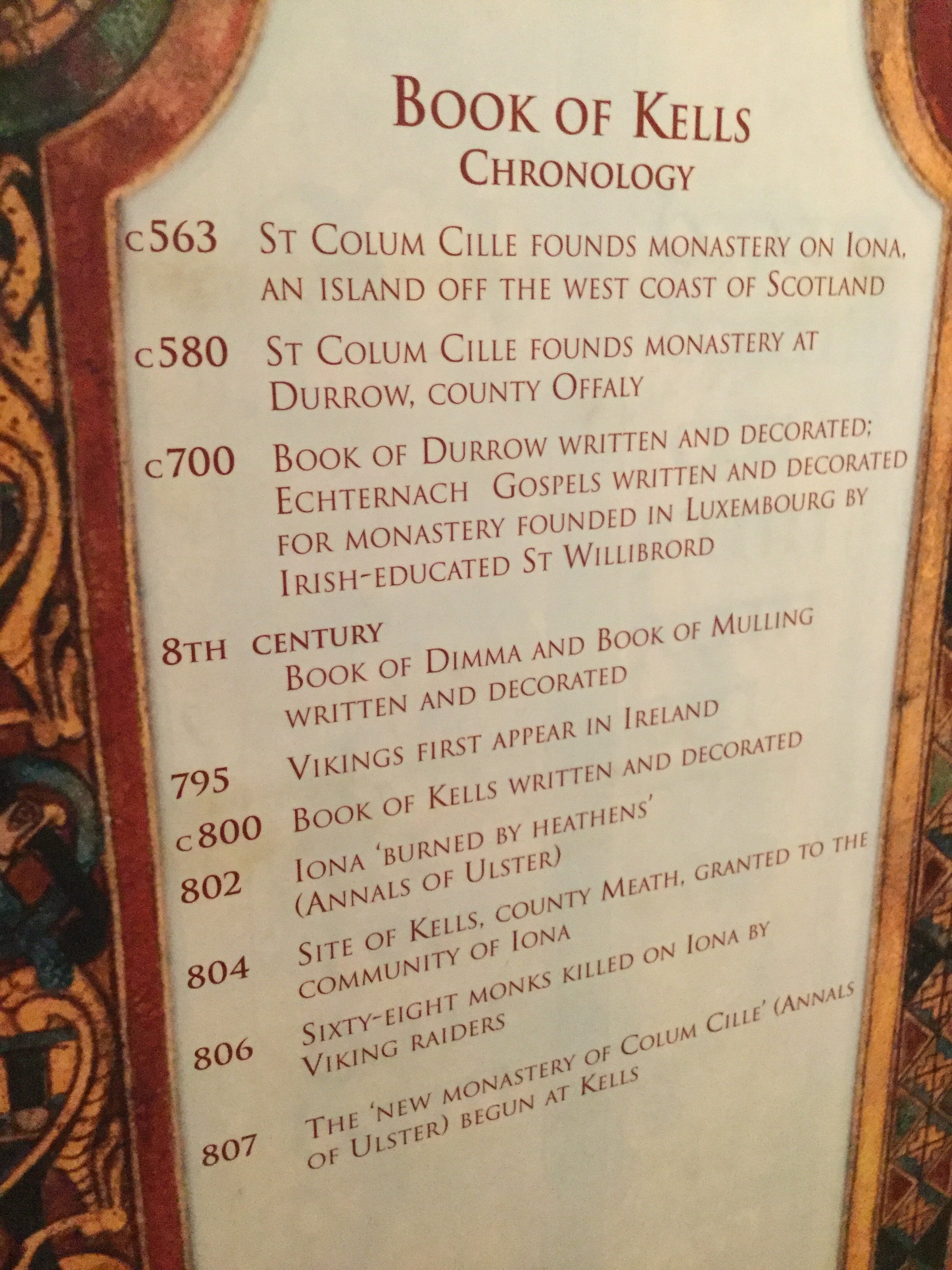

I love books! Before the pandemic I frequented author talks, literary festivals, bookstores, libraries and museums. I studied library and information science in graduate school. So, when Stephanie and I found out that we were going to be in Dublin, we planned a separate day before we met up with our tour group to view one of the most famous books in the world - the Book of Kells. Once again, our visit was pre-Covid-19 so we stood in line with other people and walked around the exhibit amidst a crowd. It was a communal experience. In contrast, my time in quarantine at home in America has been mostly solitary but it has given me the opportunity to reflect on my visit to Trinity College Dublin and the amazing survival story of the Books of Kells. Since c800, it has survived a turbulent history, from theft, to fires and wars. Now, it is enduring through the coronavirus pandemic. It is a religious book whose very existence is a testament of faith.

Steph and I entered a room where we read all about the Book of Kells, before laying eyes on the illuminated manuscript itself.

—-

The Book of Kells

“The most richly decorated of Ireland’s medieval illuminated manuscripts, the ‘Book of Kells’ may have been the work of monks from Iona, who fled Kells… in AD 806 after a Viking raid. The book, which was moved to Trinity College… in the 17th century, contains the four gospels in Latin. The scribes who copied the texts also embellished their calligraphy with intricate interlacing spirals as well as human figures and animals. Some of the dyes used were imported from as far as the Middle East.” - DK Eyewitness Travel 2018 Ireland

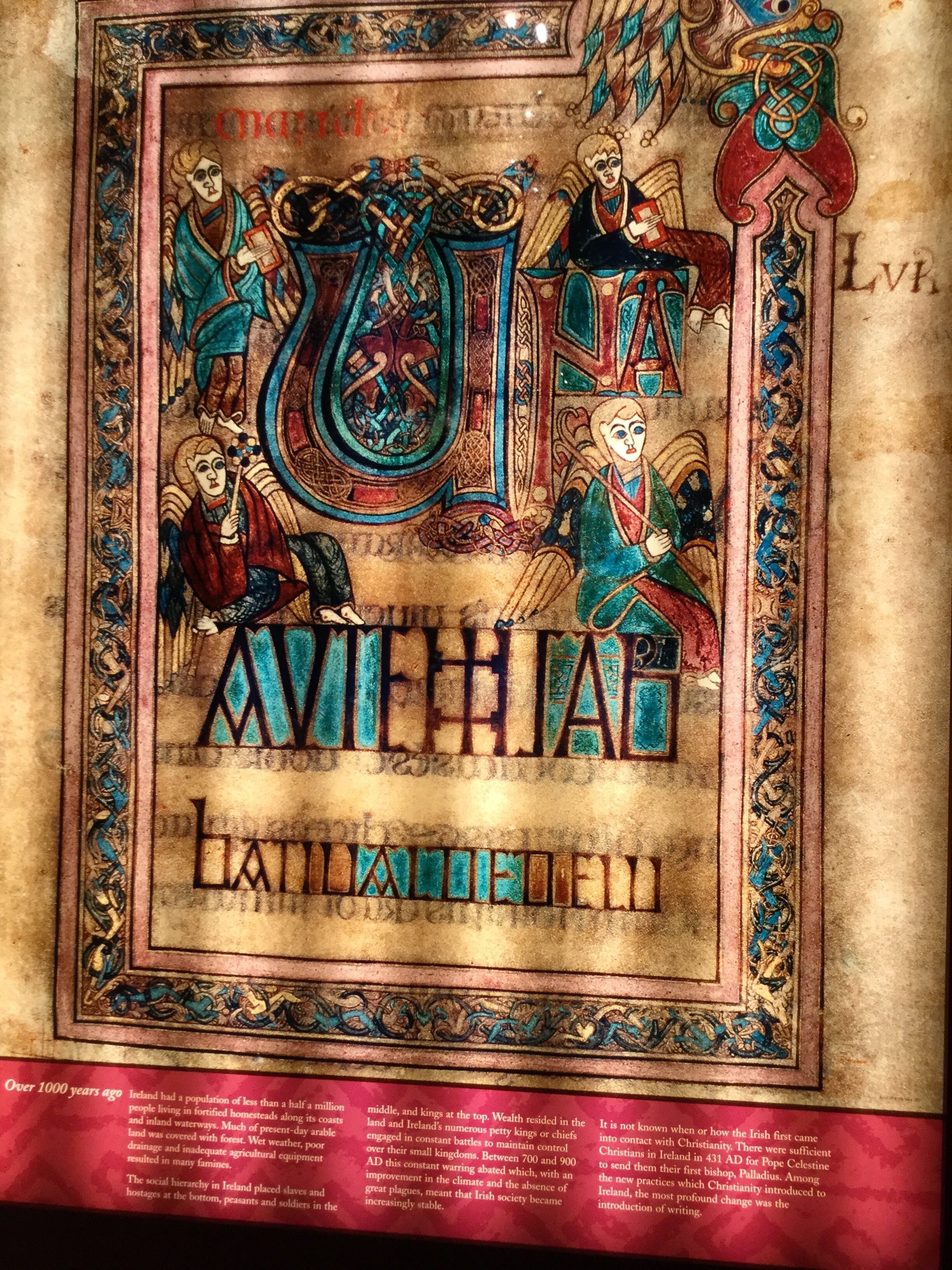

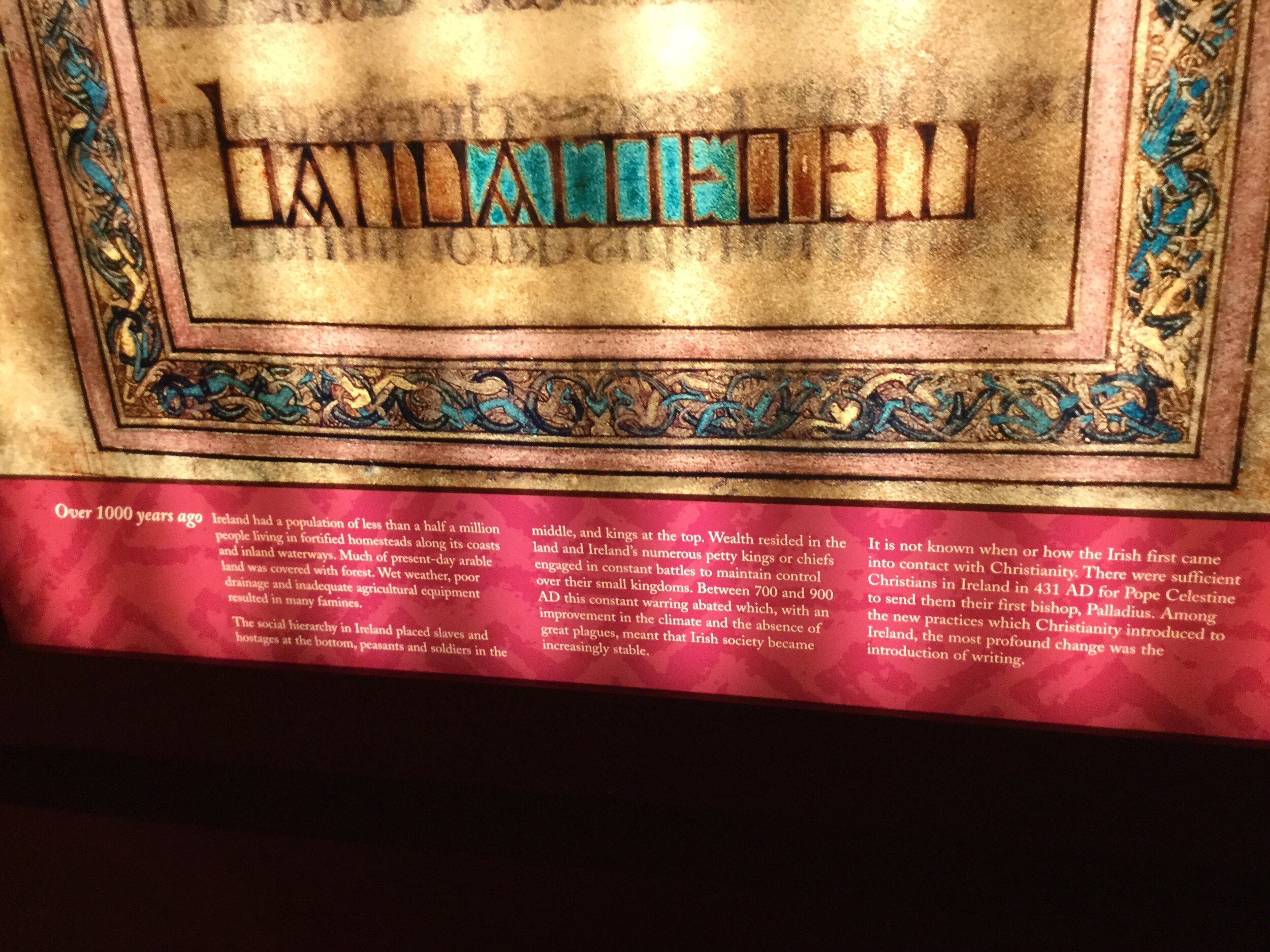

"Over 1000 years ago Ireland had a population of less than half a million people living in fortified homesteads along its coasts and inland waterways. Much of present-day arable land was covered with forest. Wet weather, poor drainage and inadequate agricultural equipment resulted in many famines.

The social hierarchy in Ireland placed slaves and hostages at the bottom, peasants and soldiers in the middle, and kings at the top. Wealth resided in the land and Ireland's numerous petty kings or chiefs engaged in constant battles to maintain control over their small kingdoms. Between 700 and 900 AD this constant warring abated which, with an improvement in the climate and the absence of great plagues, meant that Irish society became increasingly stable.

It is not known when or how the Irish first came into contact with Christianity. There were sufficient Christians In Ireland in 431 AD for Pope Celestine to send them their first bishop, Palladius. Among the new practices which Christianity introduced to Ireland, the most profound change was the introduction of writing."

It is amazing to think that the Ireland of 1,000 years ago was covered with forests. I wonder what it would have been like to stand in those mysterious woods.

It seems that Ireland’s land has always been highly prized.

I had no idea that Christianity and the introduction of writing were so closely connected to each other.

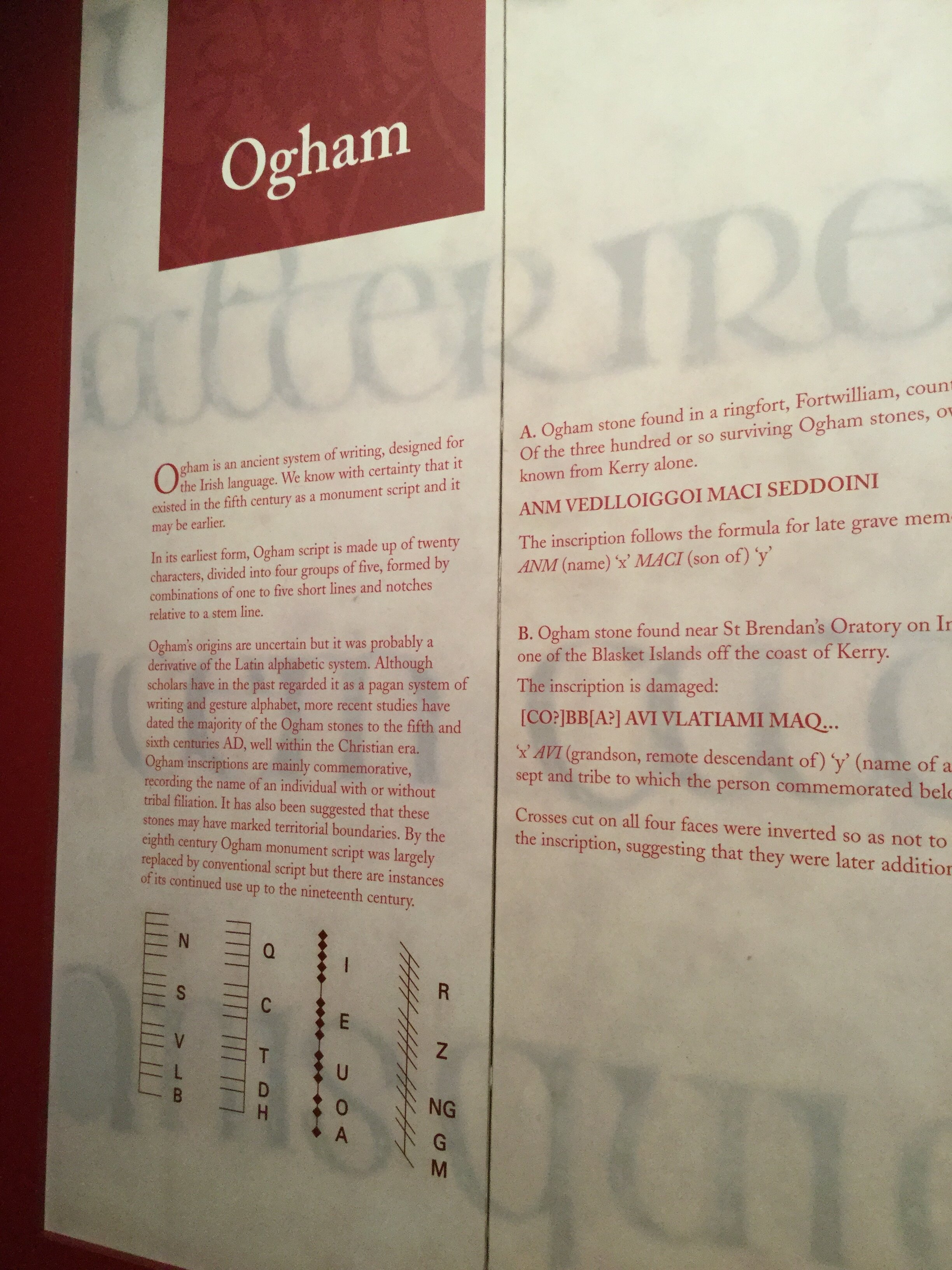

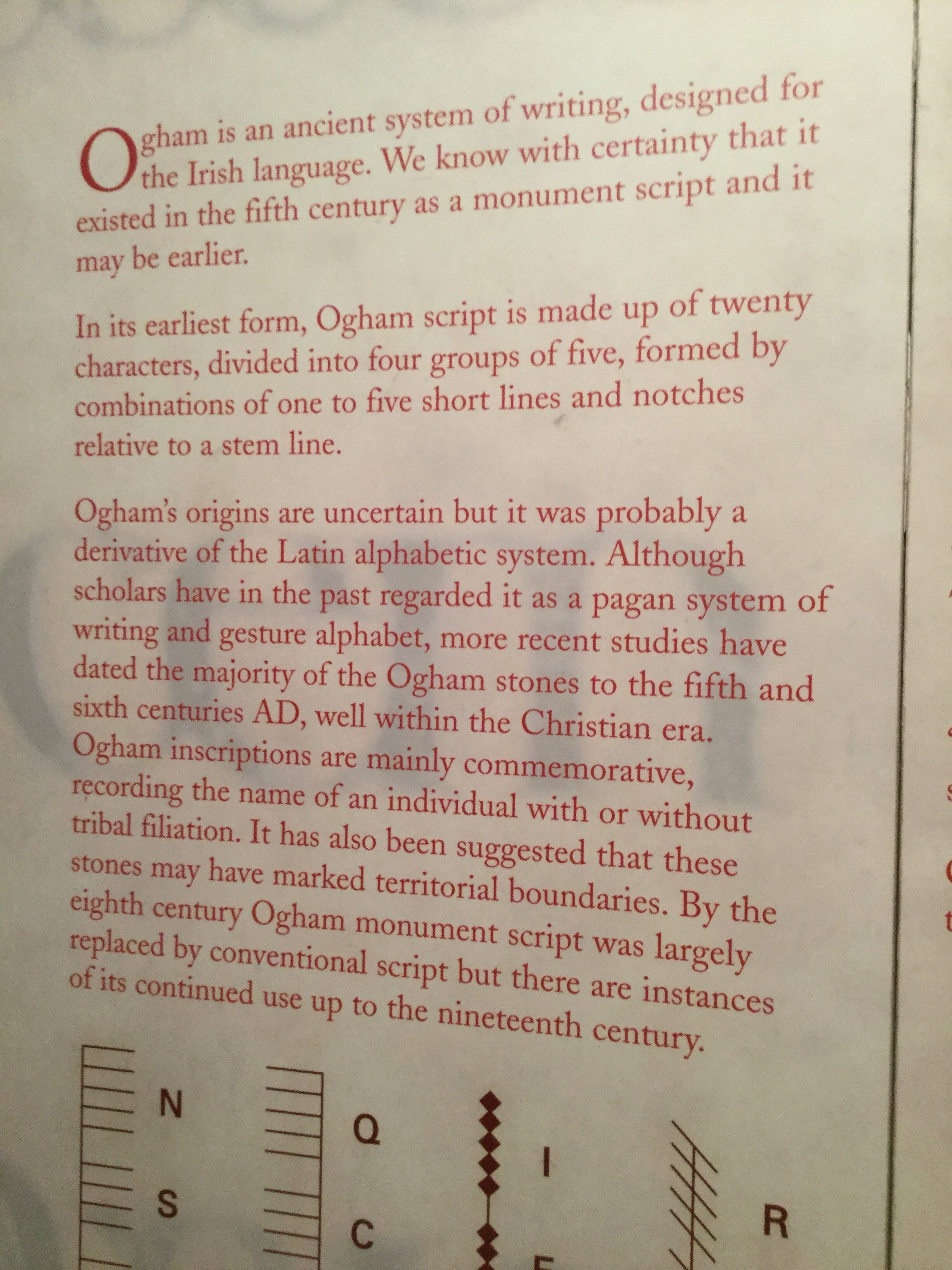

"Ogham is an ancient system of writing, designed for the Irish language. We know with certainty that it existed in the fifth century as a monument script and it may be earlier.

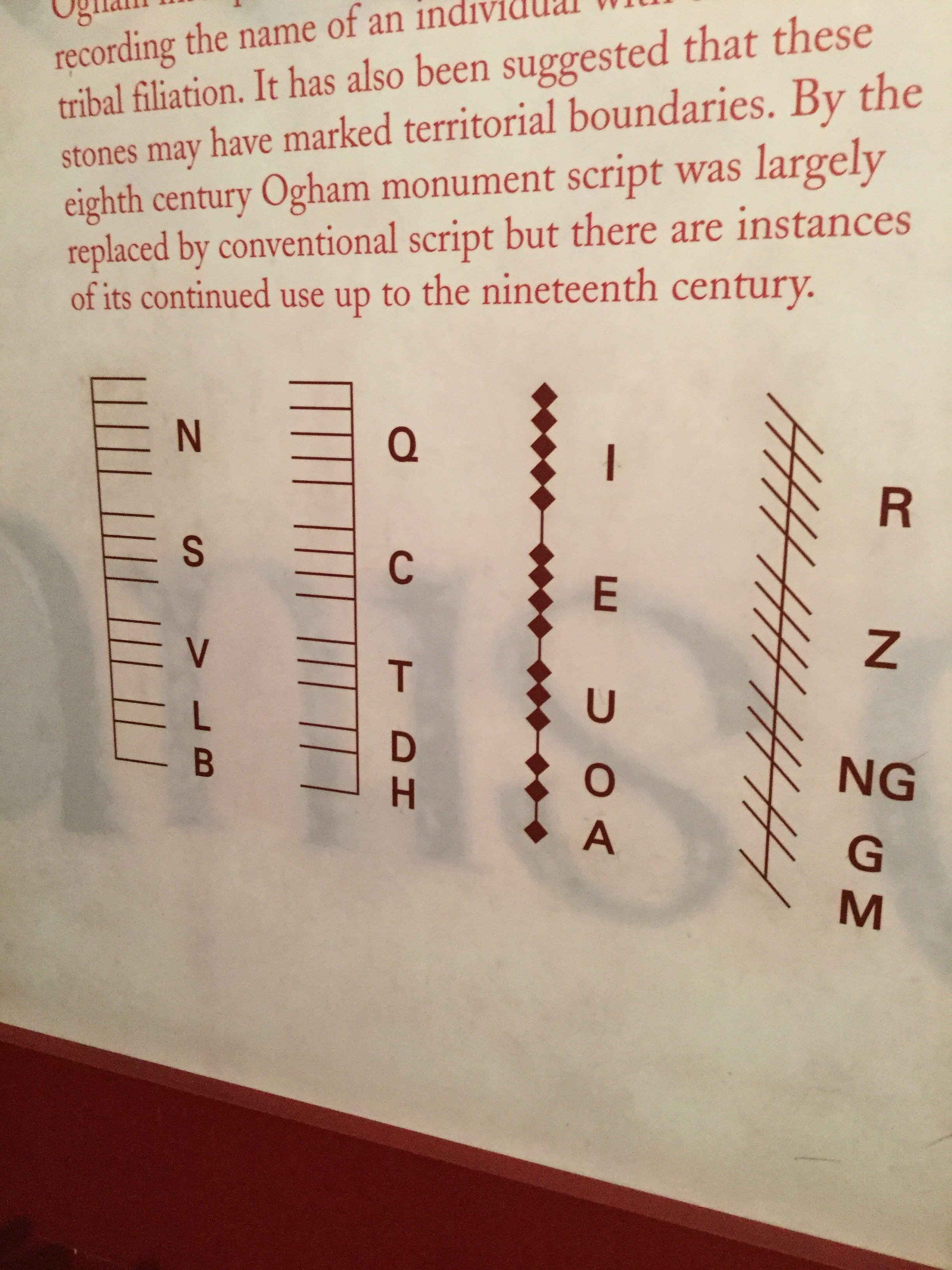

In its earliest form, Ogham script is made up of twenty characters, divided into four groups of five, formed by combinations of one to five short lines and notches relative to a stem line.

Ogham's origins are uncertain but it was probably a derivative of the Latin alphabetic system. Although scholars have in the past regarded it as a pagan system of writing and gesture alphabet, more recent studies have dated the majority of the Ogham stones to the fifth and sixth centuries AD, well within the Christian era. Ogham inscriptions are mainly commemorative, recording the name of an individual with or without tribal filiation. It has also been suggested that these stones may have marked territorial boundaries. By the eighth century Ogham monument script was largely replaced by conventional script but there are instances of its continued use up to the nineteenth century."

It’s astonishing that we know about an ancient system of writing from the fifth century.

Looking at the “R” and the “S,” I can make out what my initials would look like.

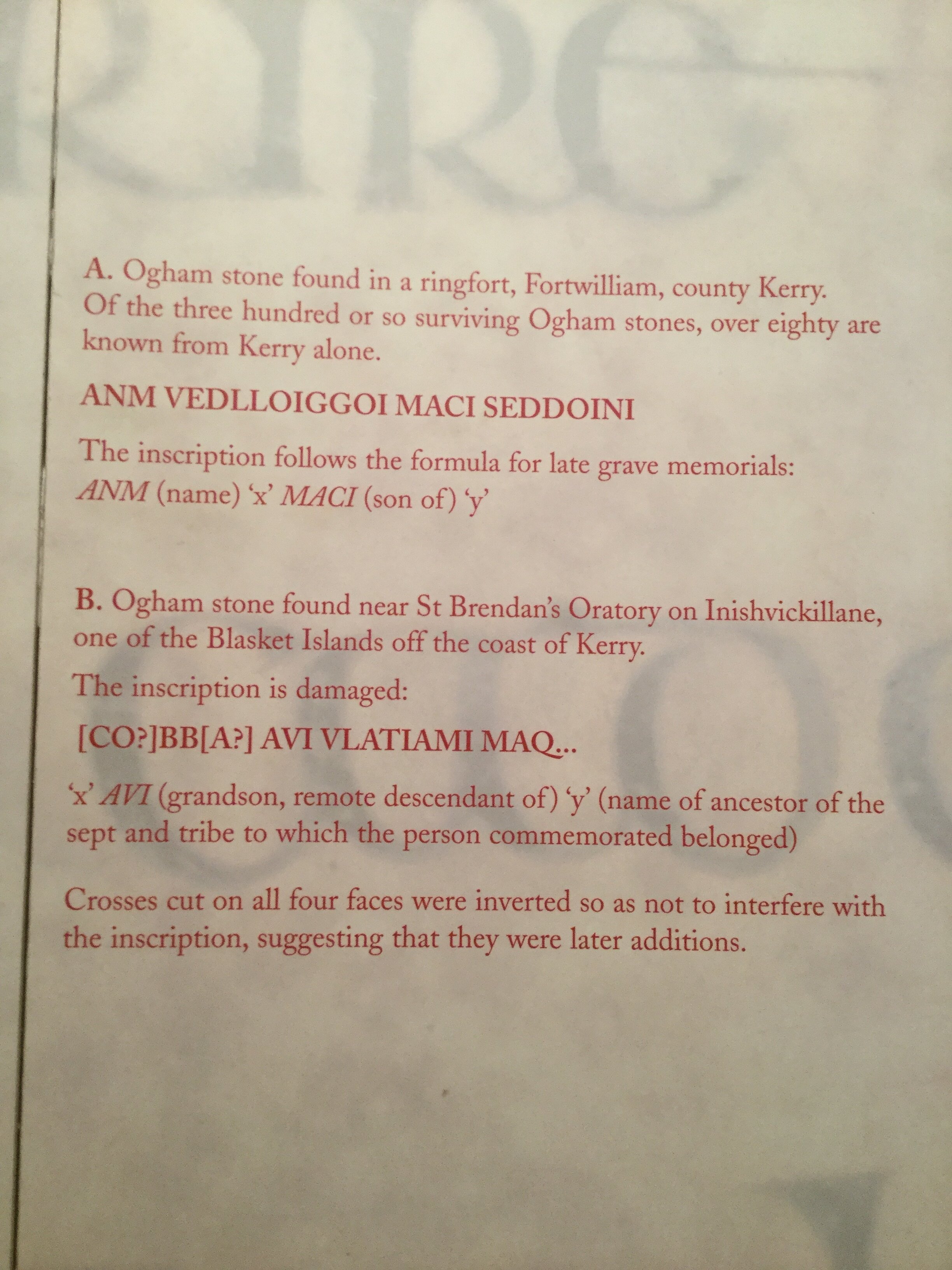

It’s interesting to note the markings for “grandson.”

'Pocket' Gospel Books

"By the 6th century Irish monks were playing a dynamic evangelical role in Britain and on the continent. The 'pocket' gospel book, which could be slipped easily into the pocket or satchel of the traveller, was an essential tool for missionaries. The lightweight design was achieved by a using a small script and many abbreviations. A trail of books belonging to Irish missionaries can still be traced today across Europe.

The Book of Mulling is an 8th-century example of the pocket gospel book, in Latin, written on vellum (calfskin). It comes from Tech-Moling (St Mullins), the monastery founded by St. Moling on the banks of the river Barrow, county Carlow. A colophon (scribal note) at the end of St. John's gospel names the scribe as Moling but is unlikely to have been the saint who died c. 697. The colophon was probably copied from an older manuscript, perhaps one written by the saint himself. Three evangelist portraits survive: Matthew, Mark and John."

I was as curious about the monks who created the Book of Kells as I was about the manuscript itself.

"The young monk entered the monastery aged about fifteen or sixteen years. He received a tonsure, or shaved head, which in the secular world was the mark of a slave. He also received a new name. He then undertook a life devoted to the study of God's word, fasts and manual work.

Monastic discipline demanded unquestioning obedience to the Rule. Food was frugal and plain; fasts were frequent and severe. Monks had to answer the call to prayer several times both night and day.

The working brethren were entrusted with responsibilities for the fields, the mills and the kitchen. Others were employed as smiths, leatherworkers, masons and carpenters.

Scribes held an honoured place in the community.

Monastic buildings, usually wooden, included a church, a refectory with a kitchen, a school, a scriptorium for book production and cells which could house two or three monks each. Many monasteries had a separate guesthouse; the community at certain times could grow to include pilgrims, travellers and visiting royalty."

Who made the Book?

The Scribes

"The Book of Kells was written by four main scribes in a formal style of script known as 'insular majuscule'. Scribe A, who copied St. John's gospel, was conservative and sober, generally leaving the decoration of his pages to others.

Scribe B, who enjoyed using coloured inks and calligraphic flourishes, was responsible for finishing certain sections and pages."

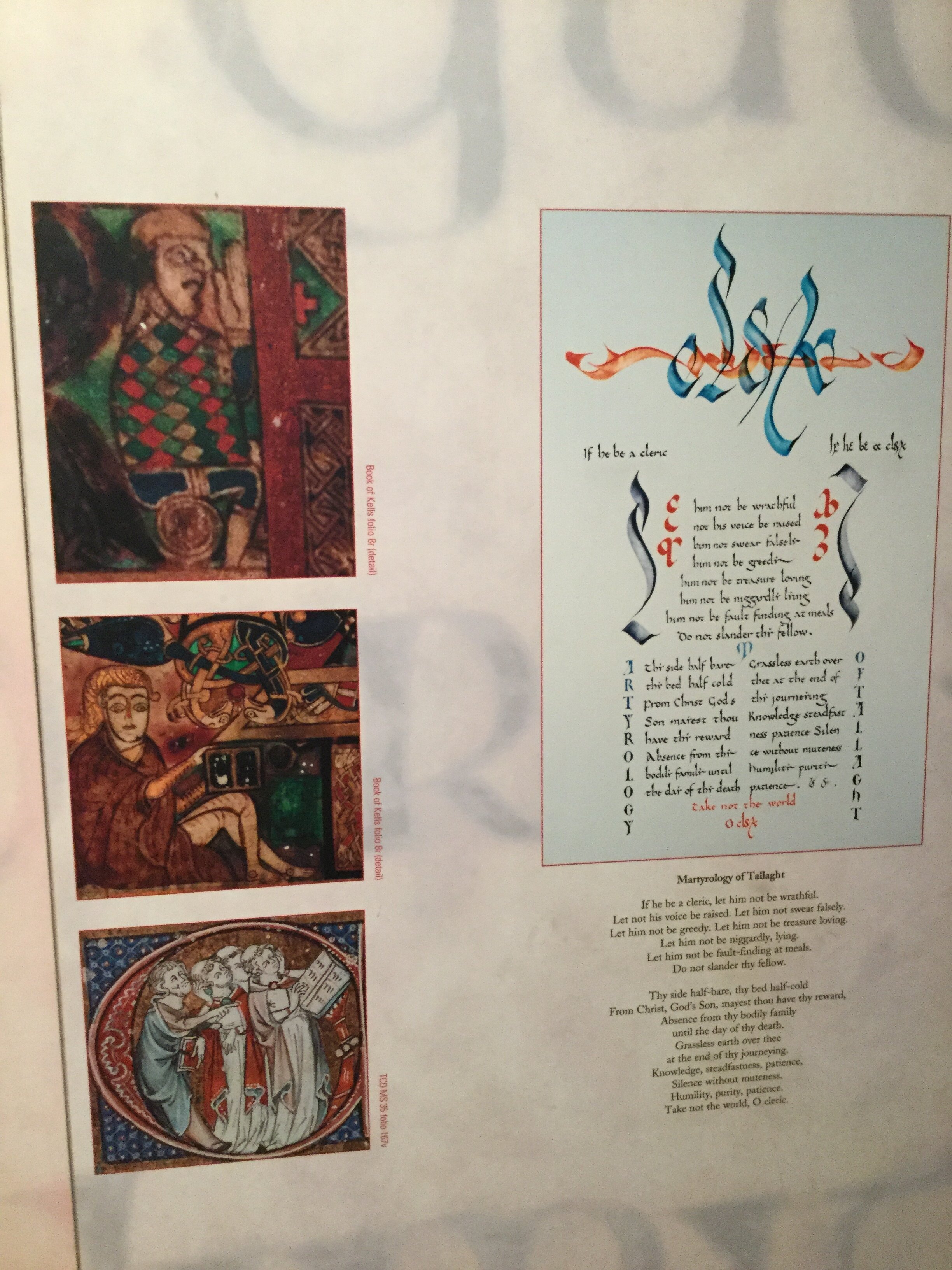

If he be a cleric, let him not be wrathful.

Let not his voice be raised. Let him not swear falsely.

Let him not be greedy. Let him not be treasure loving.

Let him not be niggardly, lying.

Let him not be fault-finding at meals.

Do not slander thy fellow.

Thy side half-bare, thy bed half-cold

From Christ, God's son, mayest thou have thy reward,

Absence from thy bodily family

until the day of thy death.

Grassless earth over thee

at the end of thy journeying.

Knowledge, steadfastness, patience,

Silence without muteness.

Humility, purity, patience.

Take not the world, O cleric.

"The Evangelist John portrayed as a scribe: he holds a pen in his right hand, and his inkwell, made from a cow horn, is placed below his throne, above his right foot." -The Book Of Kells Official Guide By Bernard Meehan, Thames & Hudson

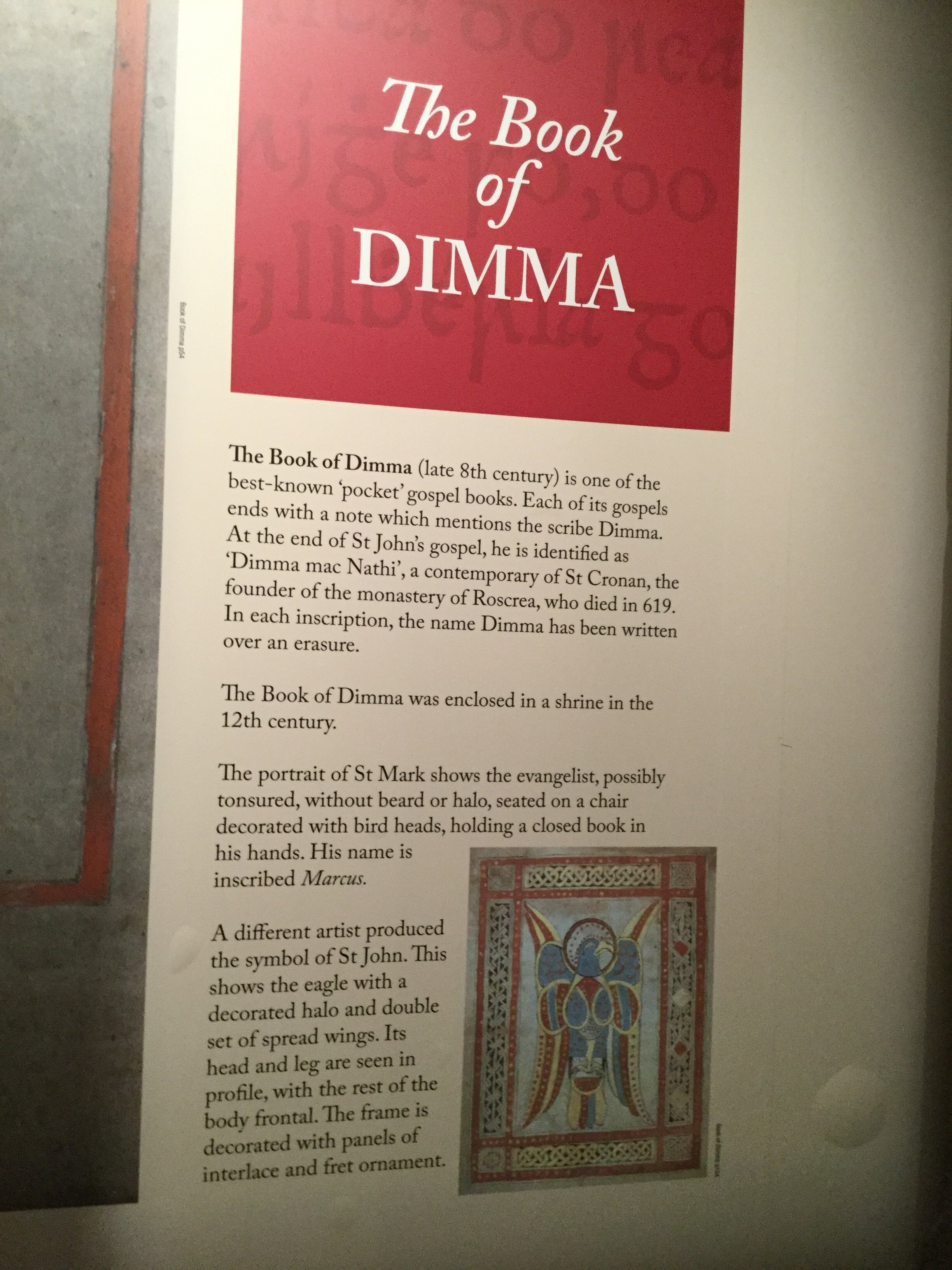

The Book of Dimma

"The Book of Dimma (late 8th century) is one of the best-known 'pocket' gospel books. Each of its gospels ends with a note which mentions the scribe Dimma. At the end of St John's gospel, he is identified as 'Dimma mac Nathi', a contemporary of St. Cronan, the founder of the monastery of Roscrea, who died in 619. In each inscription, the name Dimma has been written over an erasure.

The Book of Dimma was enclosed in a shrine in the 12th century.

The portrait of St. Mark shows the evangelist, possibly tonsured, without beard or halo, seated on a chair decorated with bird heads, holding a closed book in his hands. His name is inscribed Marcus.

A different artist produced the symbol of St. John. This shows the eagle with a decorated halo and double set of spread wings. Its head and leg are seen in profile, with the rest of the body frontal. The frame is decorated with panels of interlace and fret ornament."

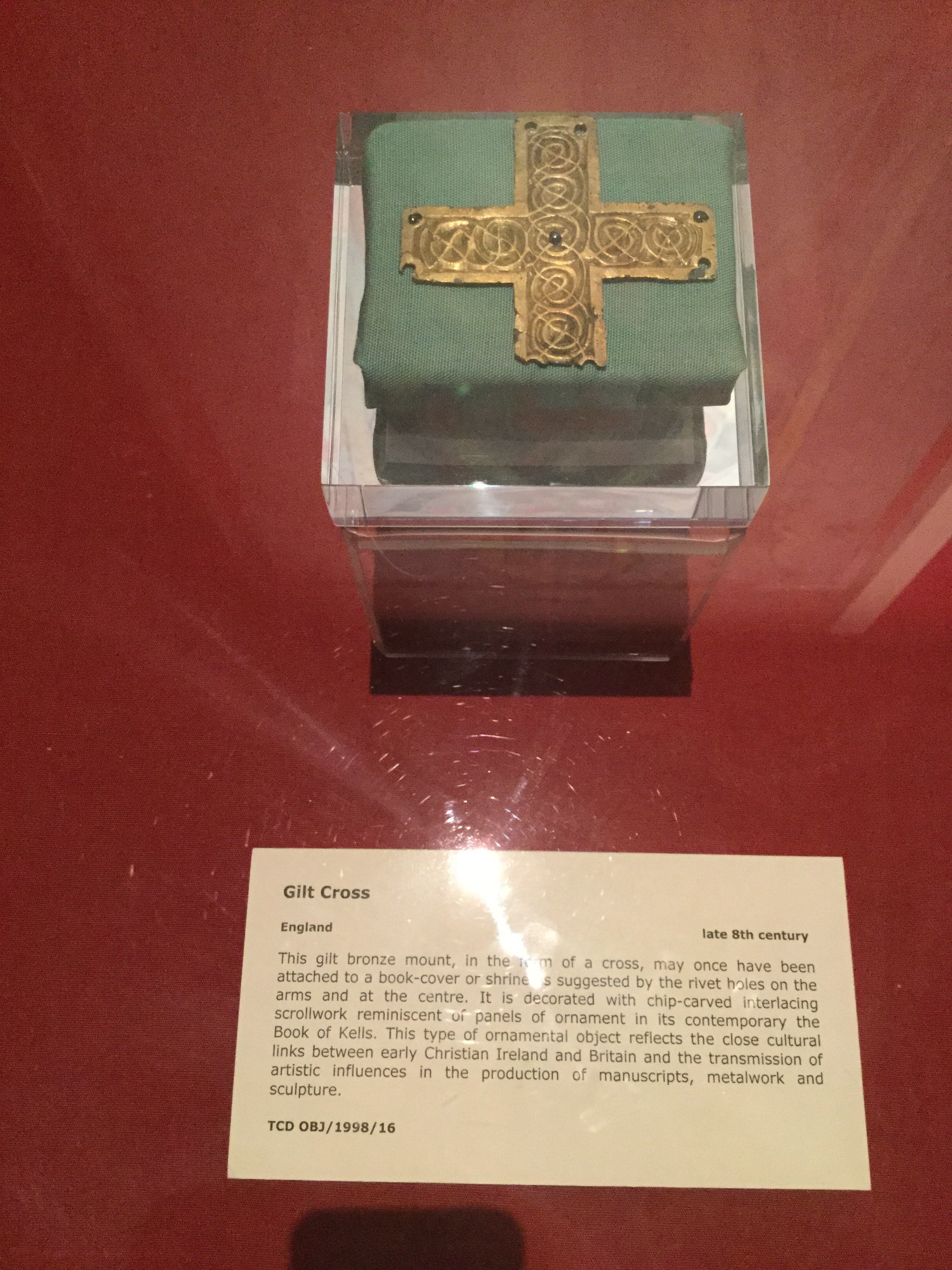

England late 8th century

"This gilt bronze mount, in the form of a cross, may once have been attached to a book-cover or shrine as suggested by the rivet holes on the arms and at the centre. It is decorated with chip-carved interlacing scrollwork reminiscent of panels of ornament in its contemporary the Book of Kells. This type of ornamental object reflects the close cultural links between early Christian Ireland and Britain and the transmission of artistic influences in the production of manuscripts, metalwork and sculpture."

Learning about the Book of Kells is a journey into another time.

"Evangelist symbols prefacing Matthew's Gospel: the man of Matthew, the lion of Mark, the eagle of John, and the calf of Luke. All have haloes and wings." -The Book Of Kells Official Guide, Thames & Hudson

Did the Viking raiders really have to kill the monks in 806? That just speaks to the brutality of the time.

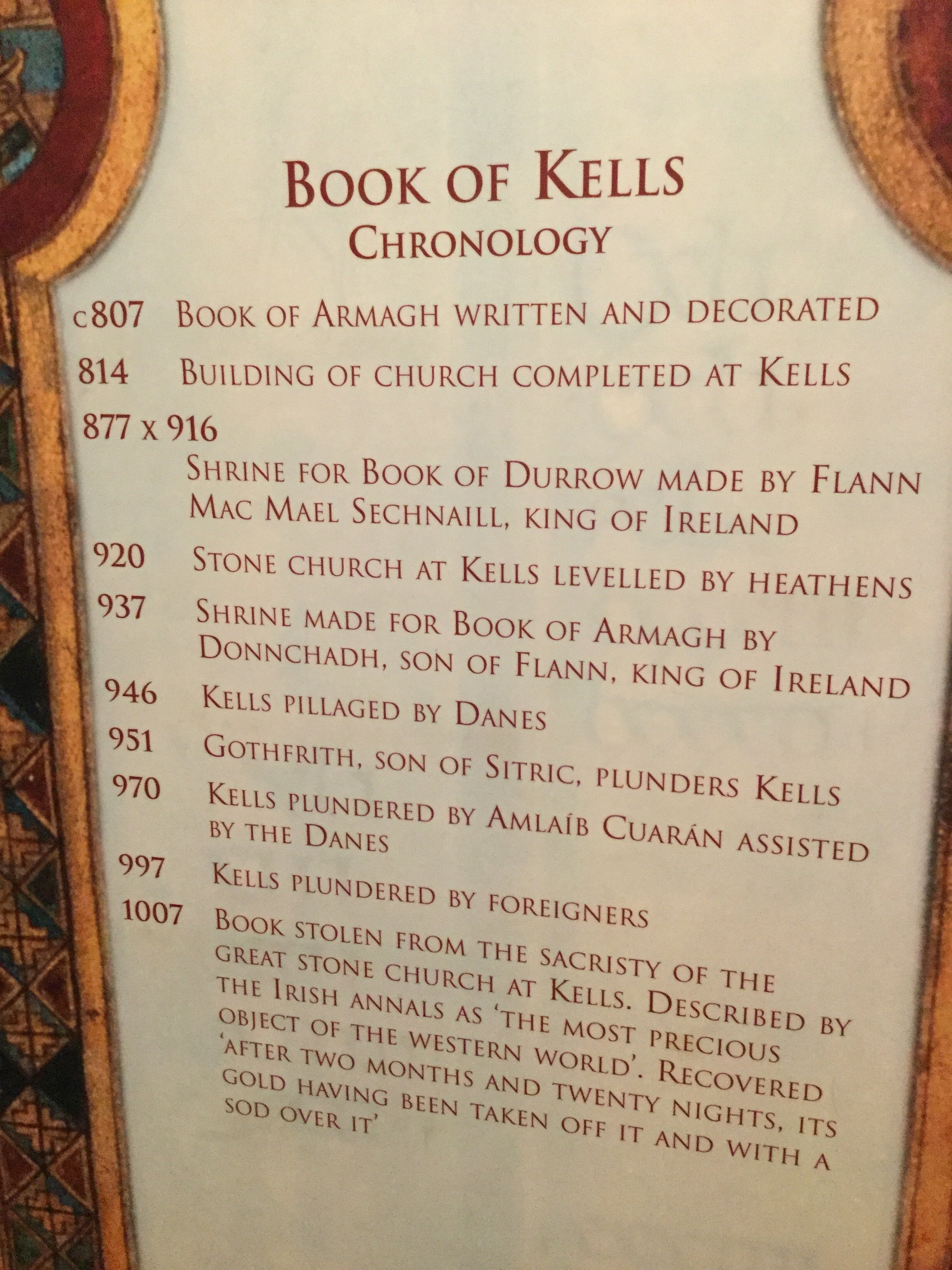

I wonder who the thief was and how this person was found. We’re lucky the Book of Kells was recovered.

Fires, rebellion, wars...It's amazing this book survived at all!

"A double-armed cross with eight circles, referring to the eight days of Christ's Passion… It contains minutely executed interlacings of stylized lions (mostly in red), snakes (yellow) and peacocks (purple)…" - The Book of Kells Official Guide by Bernard Meehan, Thames & Hudson

While plans are underway to add a visitor center and the current viewing experience is enhanced with a new display case (https://www.rte.ie/news/2020/0913/1164894-trinity-book-of-kells/), there was an element of intrigue on the day of our visit. We saw a group of men in suits who were escorted into a room ahead of us, while we joined a line that was merging with the rest of the visitors in an area that featured an exhibit explaining the significance of the illuminated manuscript. We were curious about the seemingly exclusive space those VIPS had just disappeared into and the mystery made us all the more eager to follow them.

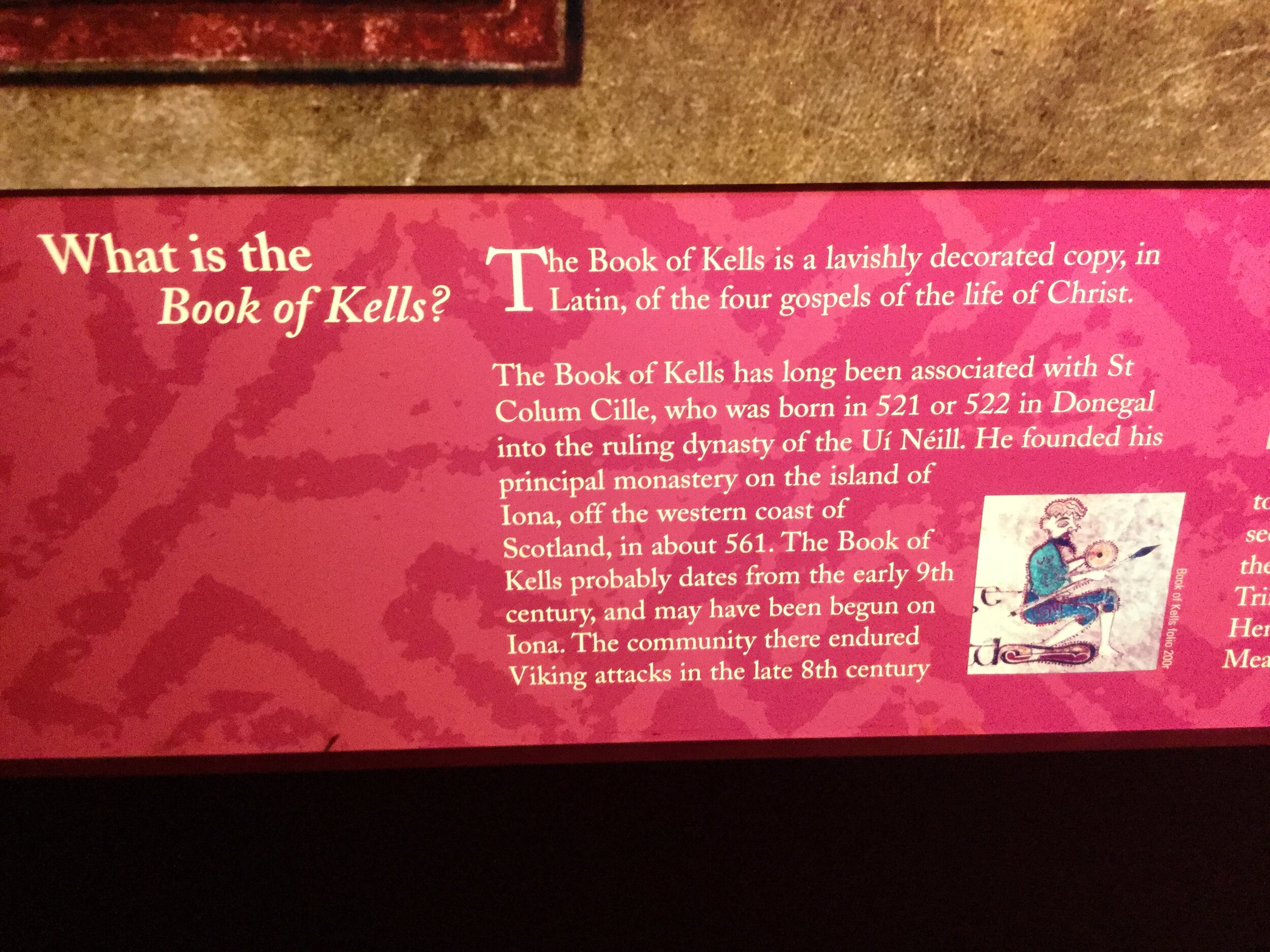

"The Book of Kells is a lavishly decorated copy, in Latin, of the four gospels of the life of Christ.

The Book of Kells has long been associated with St Colum Cille, who was born in 521 or 522 in Donegal into the ruling dynasty of the Uí Néill. He founded his principal monastery on the island of Iona, off the western coast of Scotland, in about 561. The Book of Kells probably dates from the early 9th century, and may have been begun on Iona. The community there endured Viking attacks in the late 8th century..."

“…and subsequently established a monastery in Kells, county Meath. The Book is first mentioned in the Annals of Ulster, which recorded that in 1007 'the great gospel book of Colum Cille' was stolen from the stone church at Kells but later recovered. The Book of Kells was sent to Dublin around 1653 for reasons of security as the church fell to ruin during the Cromwellian period. It came to Trinity College through the agency of Henry Jones, after he became bishop of Meath in 1661."

"The Book of Kells may have been commissioned to celebrate the bicentenary of Colum Cille's death, but whether such anniversaries were marked at the time is not clear. Textual errors and the ornate nature of some of the decorated pages indicate that the Book of Kells was not intended as a daily reading text but rather as altar furniture for special occasions."

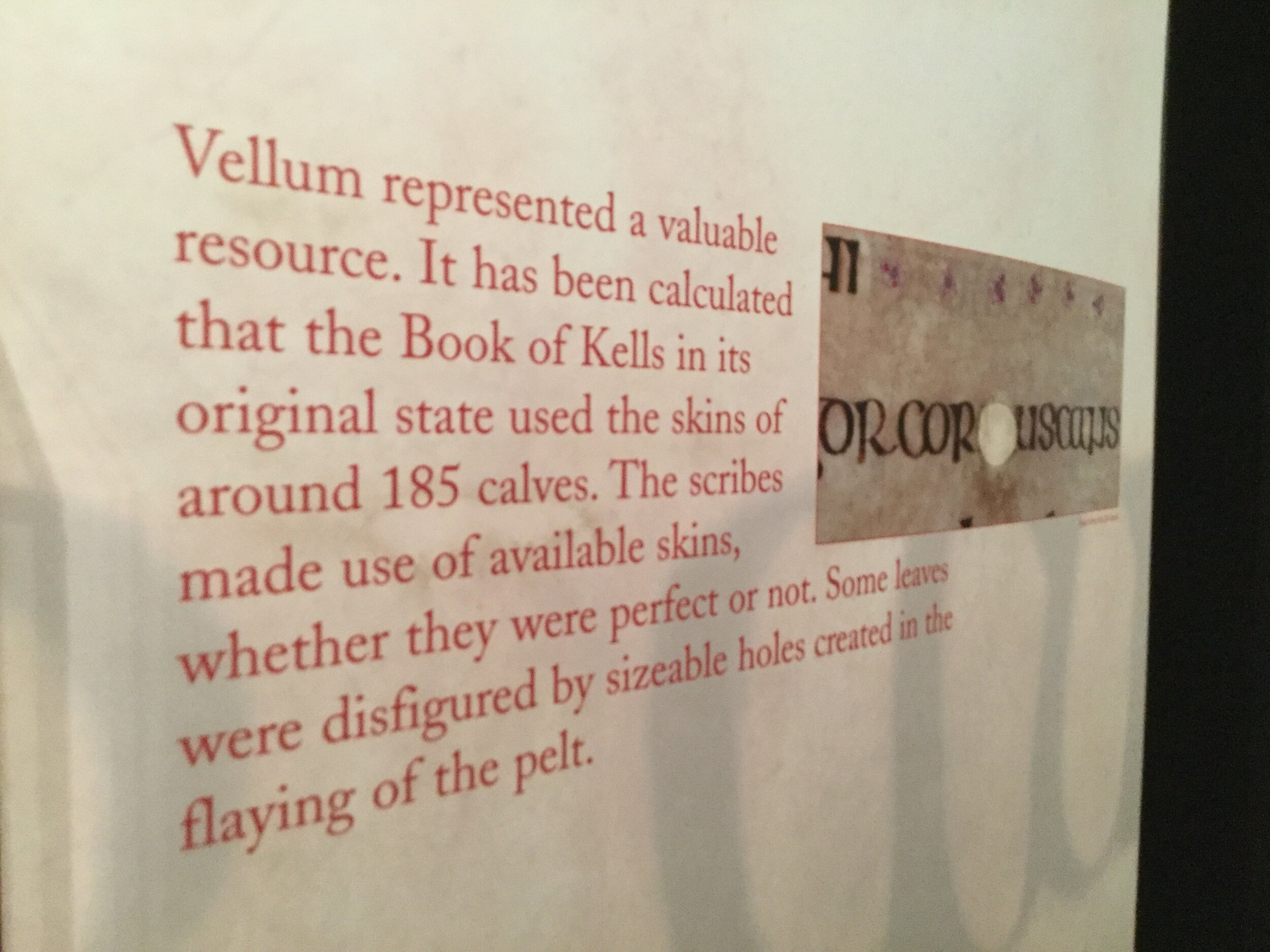

"The Book of Kells is written on vellum (calfskin). To prepare vellum, most of the hair was removed by immersing the skin in lime or excrement and then scraping it with a knife. The skin was tensioned on a frame, and a semi-circular luna knife was used to remove remaining hair and debris. The presence of hair follicles can still be detected on some leaves.

Calves.

"...assistance of magnifying instruments. Crystals may have been used, but they would probably have introduced an element of distortion.

The original binding of the Book of Kells has not survived. The boards would probably have been of thin quartered oak with slightly rounded edges. The leaves would have been sewn on cords laced to the boards. A cover of red leather - which may be surmised from over thirty such depictions in the Book of Kells - was pasted to the boards and impressed with decorative lines and stamps."

What learning does…

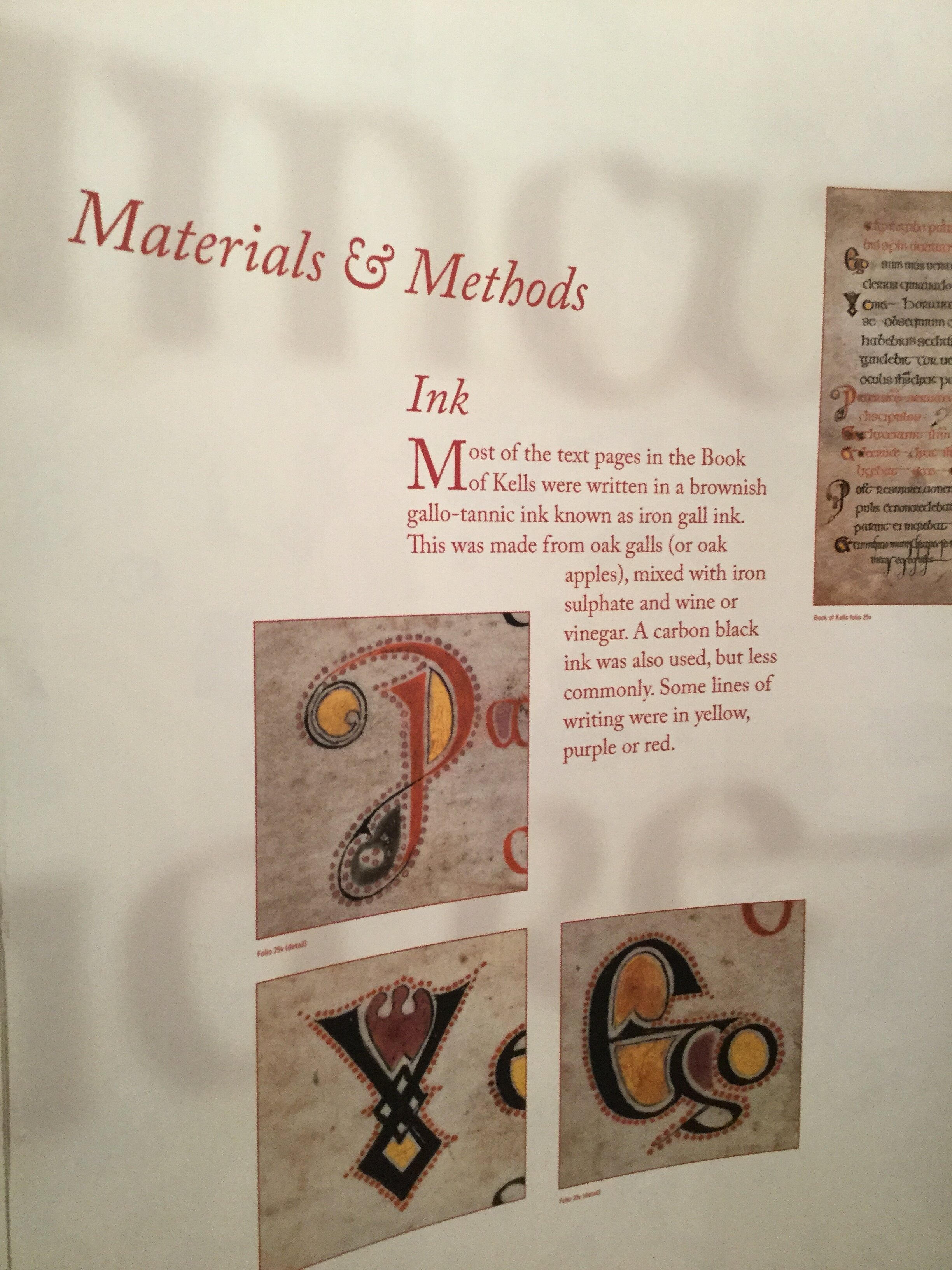

Ink

”Most of the text pages in the Book of Kells were written in a brownish gallo-tannic ink known as iron gall ink. This was made from oak galls (or oak apples), mixed with iron sulphate and wine or vinegar. A carbon black ink was also used, but less commonly. Some lines of writing were in yellow, purple or red.”

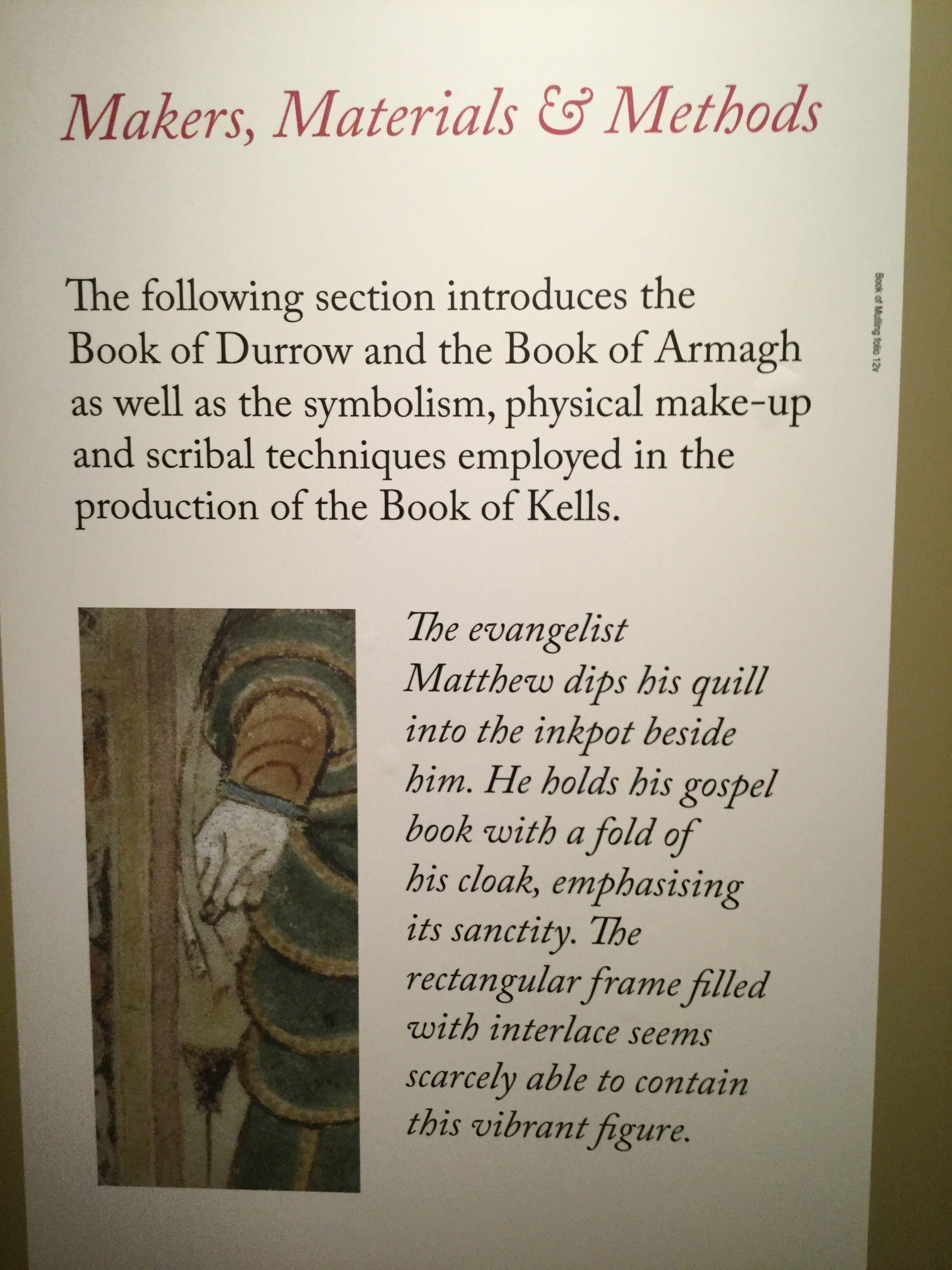

“The following section introduces the Book of Durrow and the Book of Armagh as well as the symbolism, physical make-up and scribal techniques employed in the production of the Book of Kells.

The evangelist Matthew dips his quill into the inkpot beside him. He holds his gospel book with a fold of his cloak, emphasising its sanctity. The rectangular frame filled with interlace seems scarcely able to contain this vibrant figure."

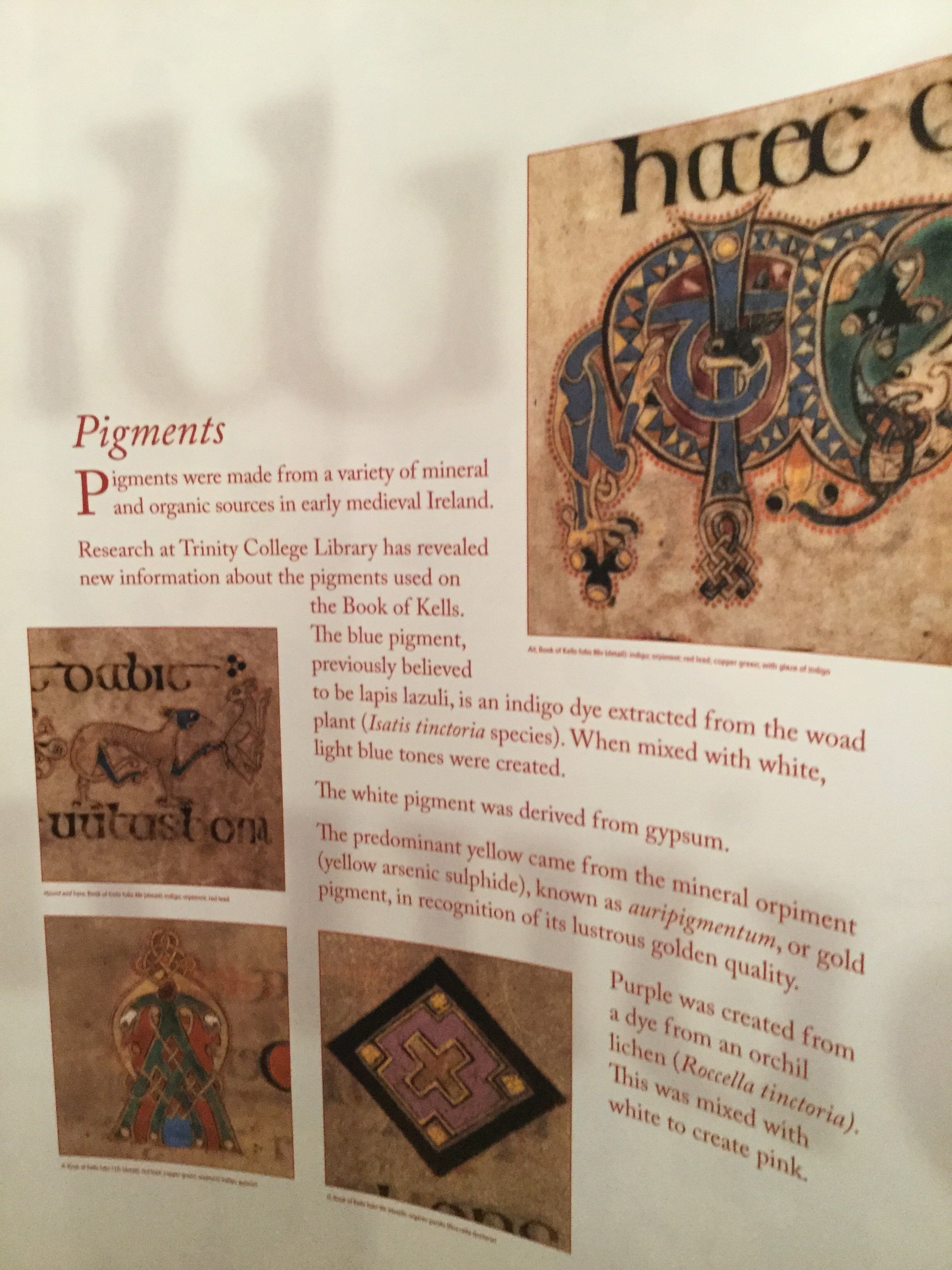

"Pigments were made from a variety of mineral and organic sources in early medieval Ireland.

Research at Trinity College Library has revealed new information about the pigments used on the Book of Kells. The blue pigment, previously believed to be lapis lazuli, is an indigo dye extracted from the woad plant (Isatis tinctoria species). When mixed with white, light blue tones were created.

The white pigment was derived from gypsum.

The predominant yellow came from the mineral orpiment (yellow arsenic sulphide), known as auripigmentum, or gold pigment, in recognition of its lustrous golden quality.

Purple was created from a dye from an orchil lichen (Roccella tinctoria). This was mixed with white to create pink."

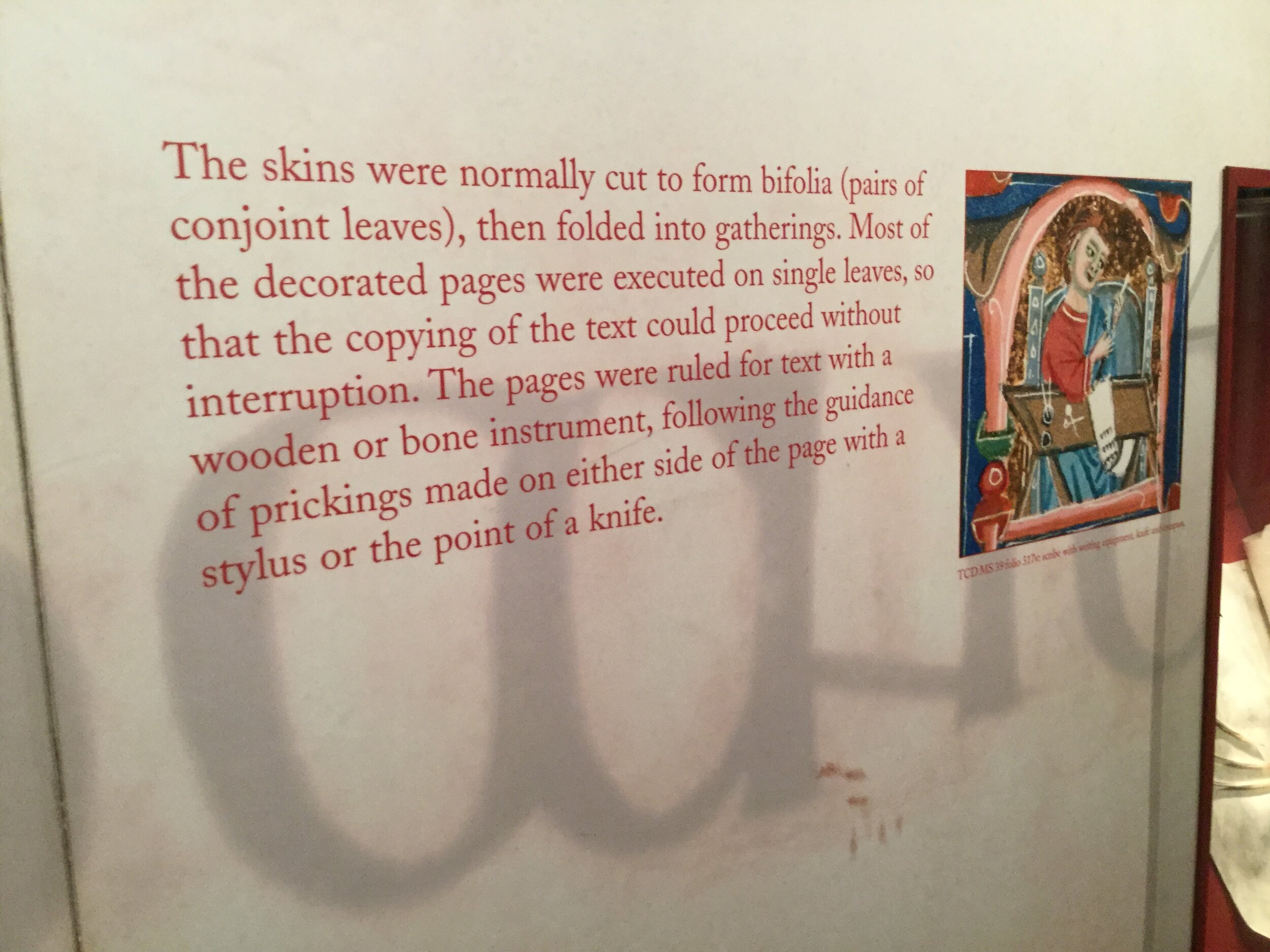

"The skins were normally cut to form bifolia (pairs of conjoint leaves), then folded into gatherings. Most of the decorated pages were executed on single leaves, so that the copying of the text could proceed without interruption. The pages were ruled for text with a wooden or bone instrument, following the guidance of prickings made on either side of the page with a stylus or the point of a knife."

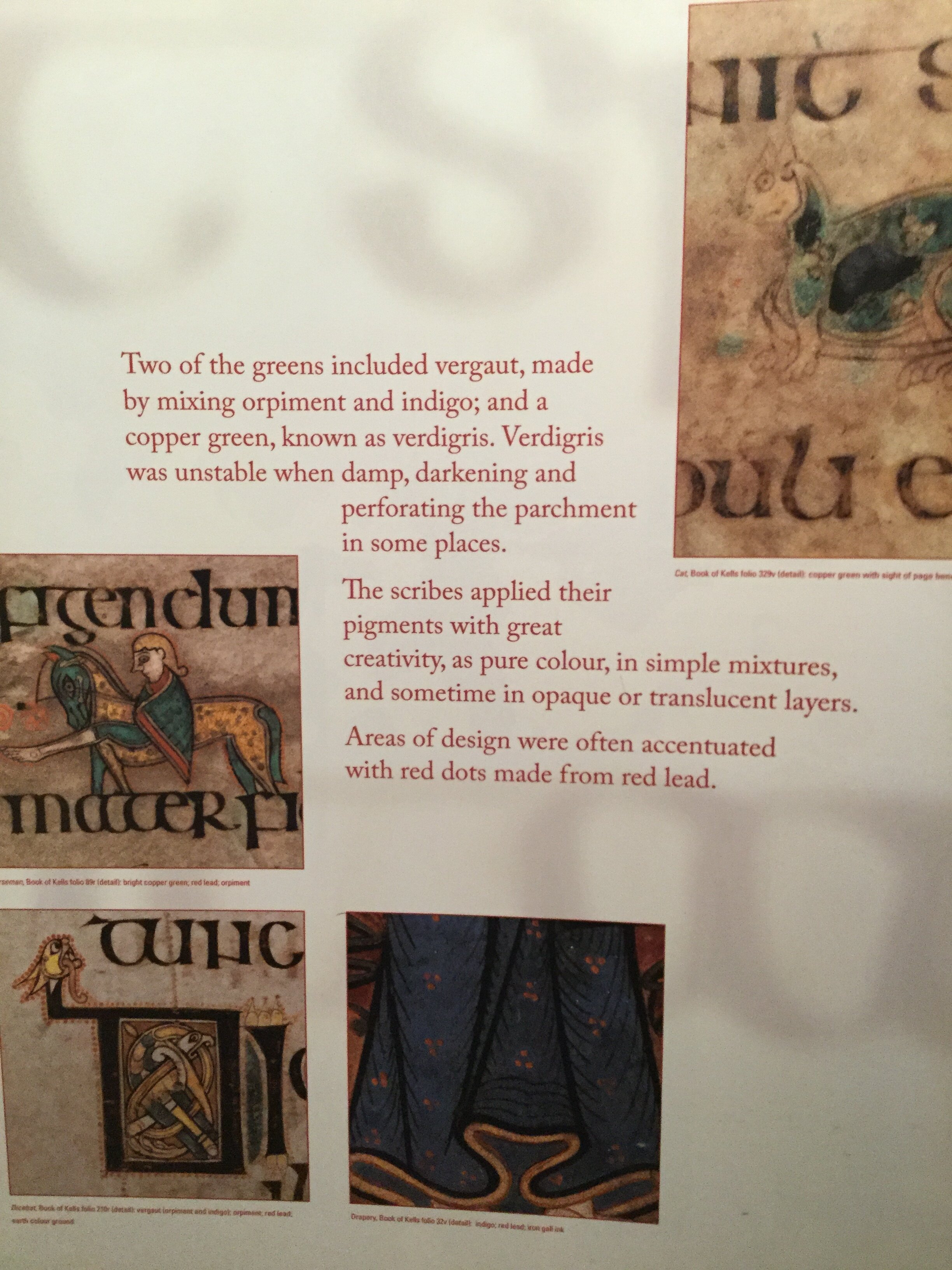

"Two of the greens included vergaut, made by mixing orpiment and indigo; and a copper green, known as verdigris. Verdigris was unstable when damp, darkening and perforating the parchment in some places.

The scribes applied their pigments with great creativity, as pure colour, in simple mixtures, and sometime in opaque or translucent layers.

Areas of design were often accentuated with red dots made from red lead."

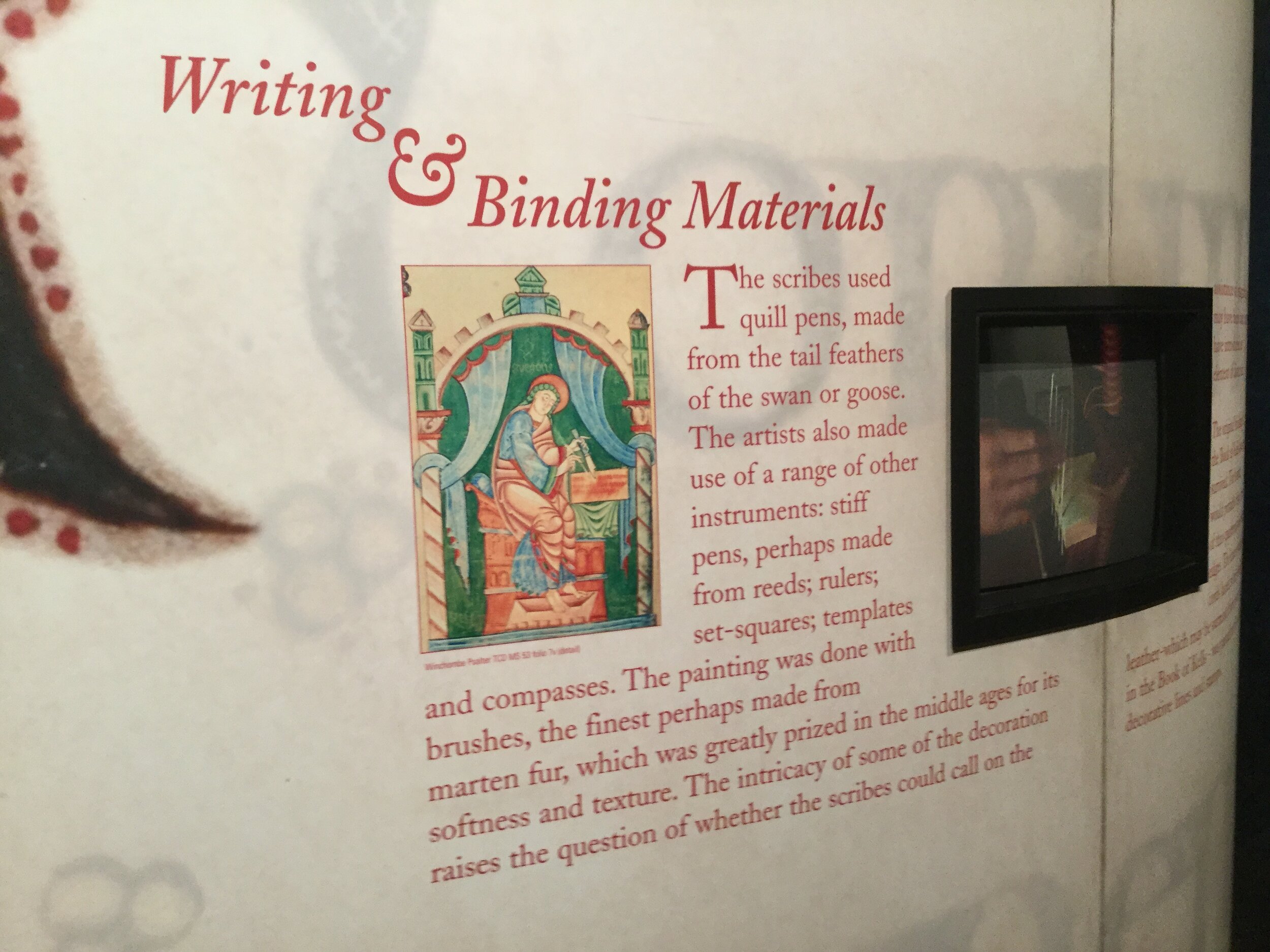

"The scribes used quill pens, made from the tail feathers of the swan or goose. The artists also made use of a range of other instruments: stiff pens, perhaps made from reeds; rulers; set-squares; templates and compasses. The painting was done with brushes, the finest perhaps made from marten fur, which was greatly prized in the middle ages for its softness and texture. The intricacy of some of the decoration raises the question of whether the scribes could call on the..."

Quill pens.

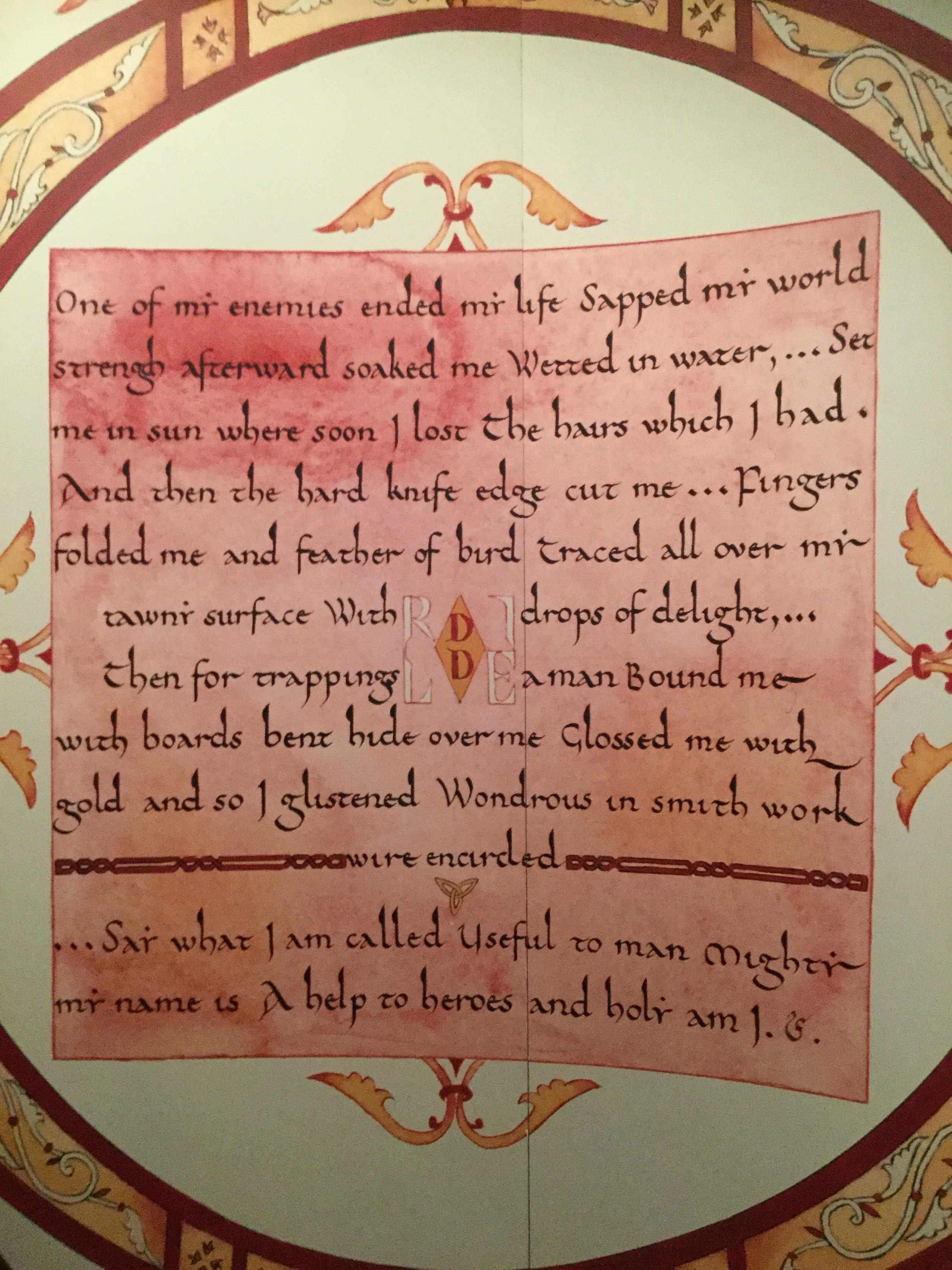

"One of my enemies ended my life

Sapped my world strength

afterward soaked me

Wetted in water,

…Set me in sun where soon I lost

the hairs which I had.

And then the hard knife edge

cut me…

Fingers folded me and feather of bird

traced all over my tawny surface

With drops of delight,…

Then, for trappings, a man

Bound me with boards, bent

hide over me

Glossed me with gold and so I glistened

Wondrous in smith work.

wire encircled

…Say what I am called Useful to man

Mighty my name is

A help to heroes and holy am I."

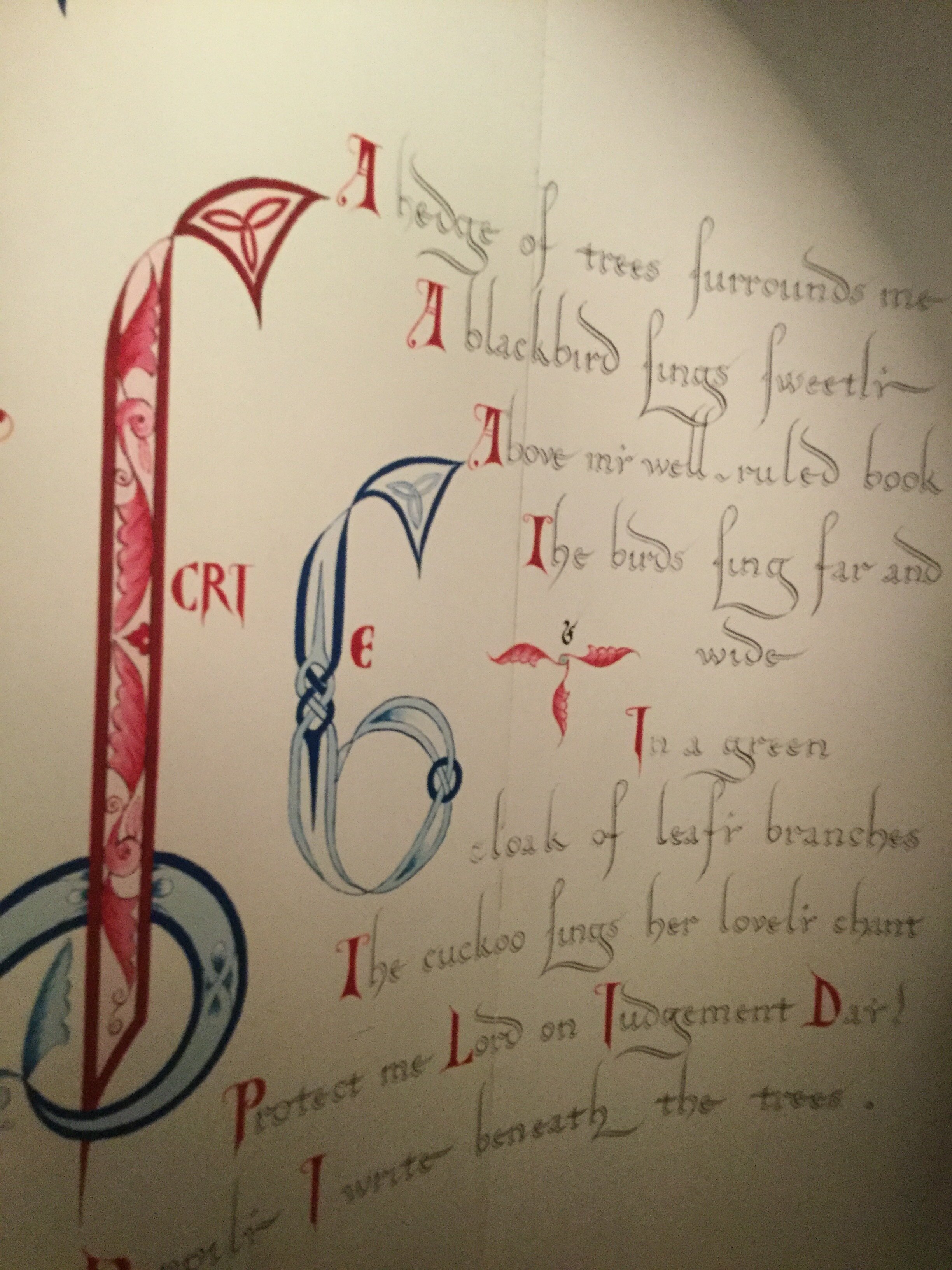

“The scribe,” as it would appear on the page.

A hedge of trees surrounds me

a blackbird sings sweetly

Above my well-ruled book

The birds sing far and wide

In a green cloak of leafy branches

The cuckoo sings her lovely chant

Protect me, Lord, on Judgement Day!

Happily I write beneath the trees

(written in Priscian's Latin Grammar by an Irish monk at St. Gallen, Switzerland, mid 9th century)

We waited for some time and then suddenly we were let into what I thought was a holding area. Everyone was rushing past me. It was a mad scramble. I was confused and I asked Steph what was happening. She told me that the Book of Kells was right in front of us. I turned and I realized the crowd was gathered around a wooden table that was covered with thick glass. I couldn’t believe it. We weren’t even in a proper room. It was more like a small hallway and right there in front of me was the Book of Kells! The exhibit itself is so elaborate and there was such a buildup of anticipation to contemplating this ancient work of art in person. The display of the actual book seemed modest in comparison.

It was not the whole Book of Kells, but rather one illustrated page and one page that is mostly text. Also on view were two pages from another medieval illuminated manuscript. The pages from the Book of Kells were from St. Matthew. We were not permitted to take photographs, so I wanted to make sure that I committed the experience to memory.

I peeked over people's shoulders and waited until I could get my chance to stand directly in front of the hallowed pages. By the time I got there, most of the onlookers had moved on. I kept reminding myself that what I was seeing was from the 9th century - so long ago. I needed to summon reverence. I needed to be still. I took a deep breath and realized that the display in front of me was beautiful in its simplicity and familiar in a way. This was still about the power of books. It was just me and pages written and decorated by monks and a message of devotion and sacrifice.

I think this is one of my favorite Irish poems. It was, “written by an Irish monk at St. Gallen, Switzerland in the 9th century.”

The lives of the monks who worked on the Book of Kells fascinated me. For some reason I had an image of elderly, learned men in my head, but they were only teens. I overhead a guide say that sometimes the monks would scribble notes in the margins, like that they were bored or wanted to go outside, which would be erased later. That anecdote stayed with me because it reminded me of their humanity while they were working on this monumental task. The guide said the monks needed to be young to have the eyesight and the stamina to do such detailed work and that the average lifespan was much shorter than ours, so their teenage years would have been closer to middle age. I wonder what those monks would think of their artistry and painstaking work continuing to inspire the world in the 21st century AD.

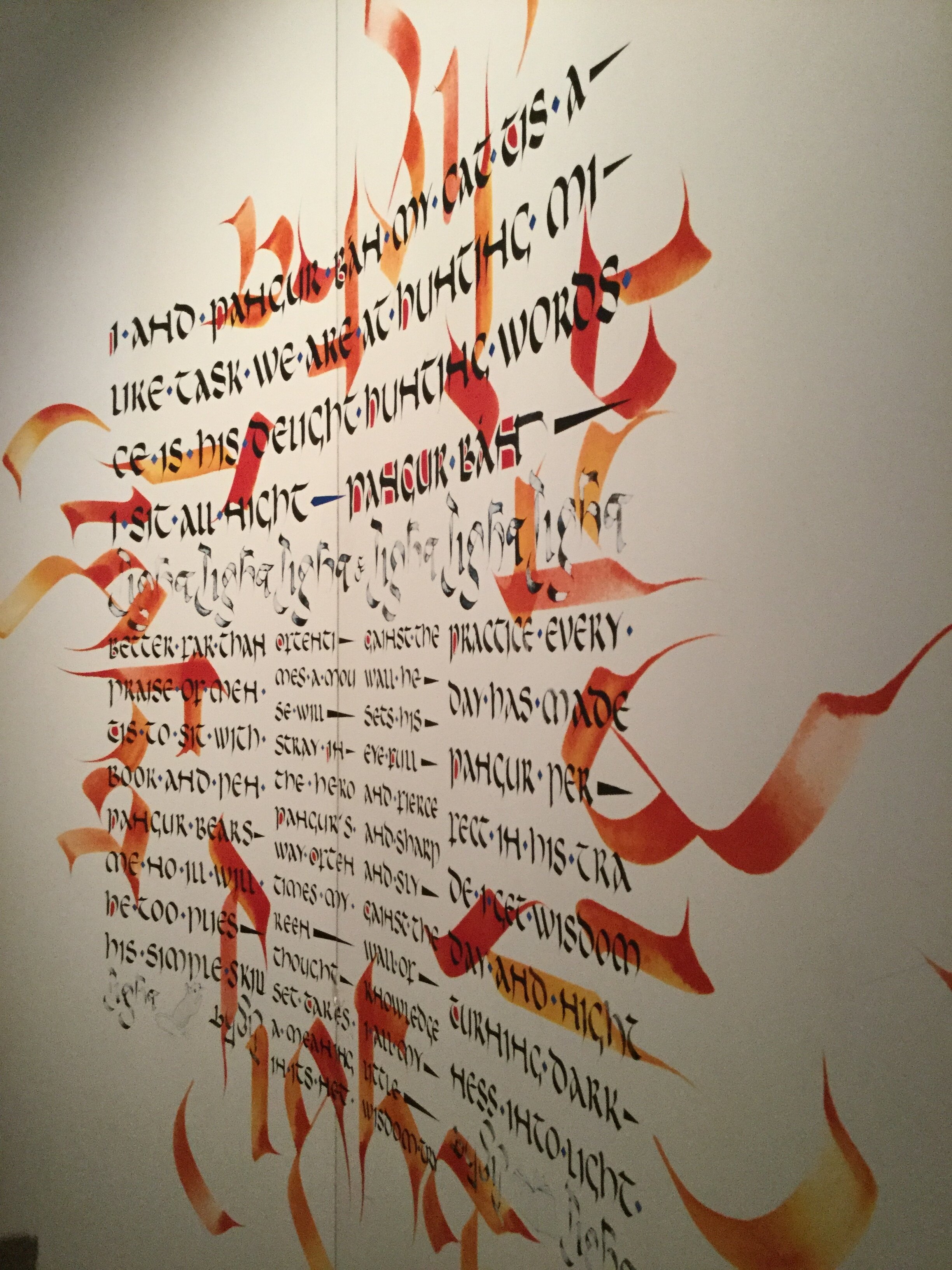

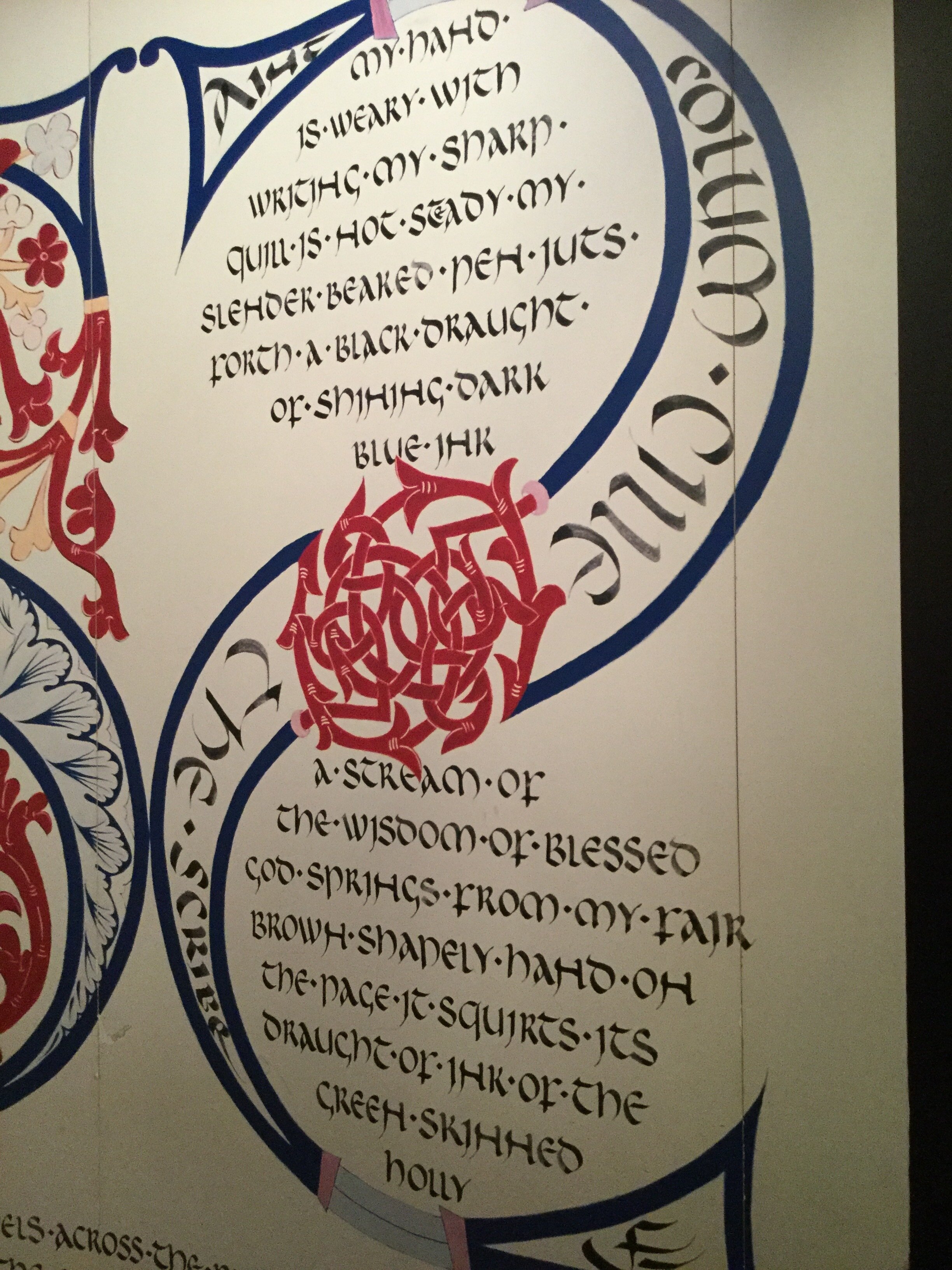

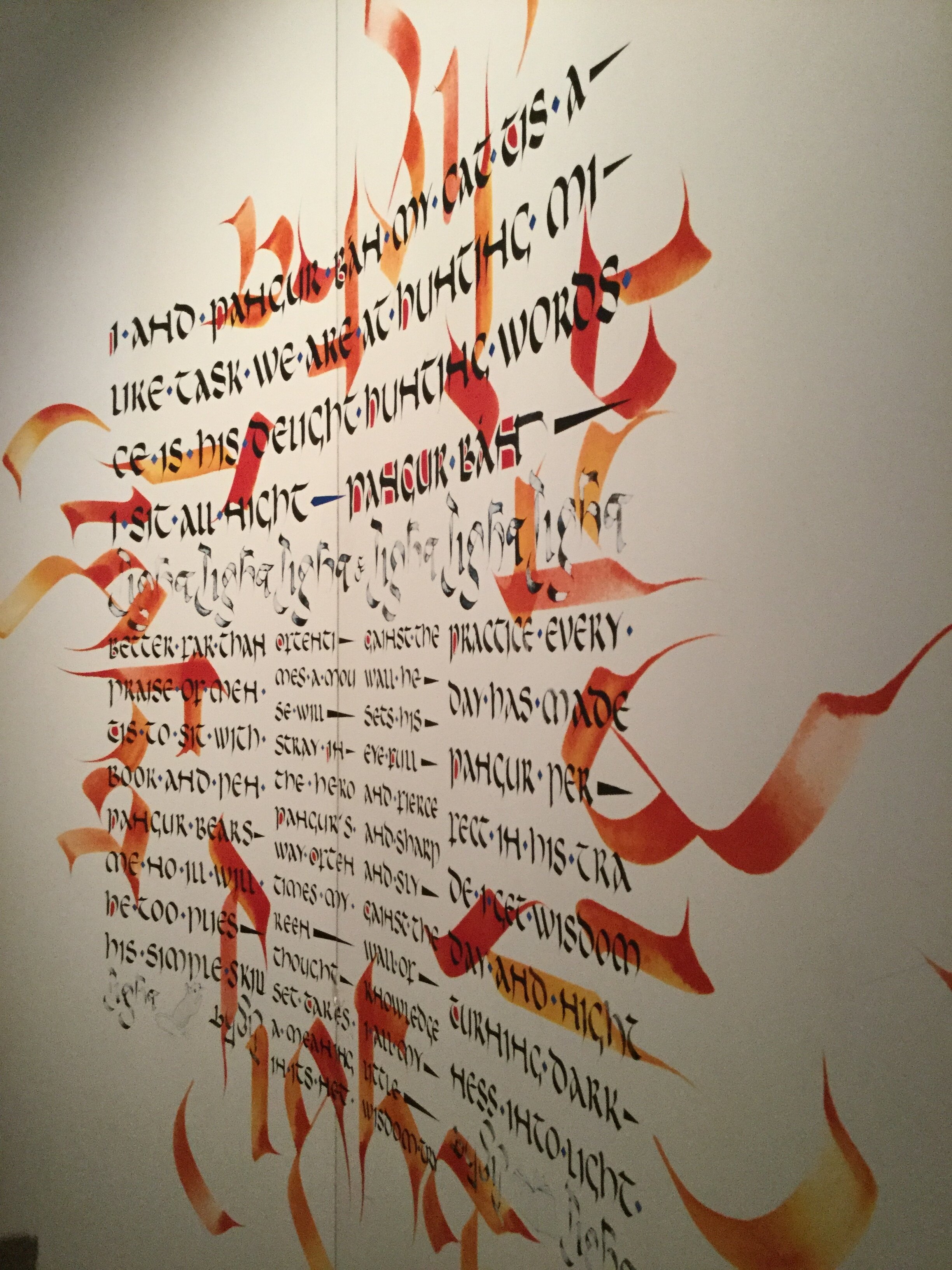

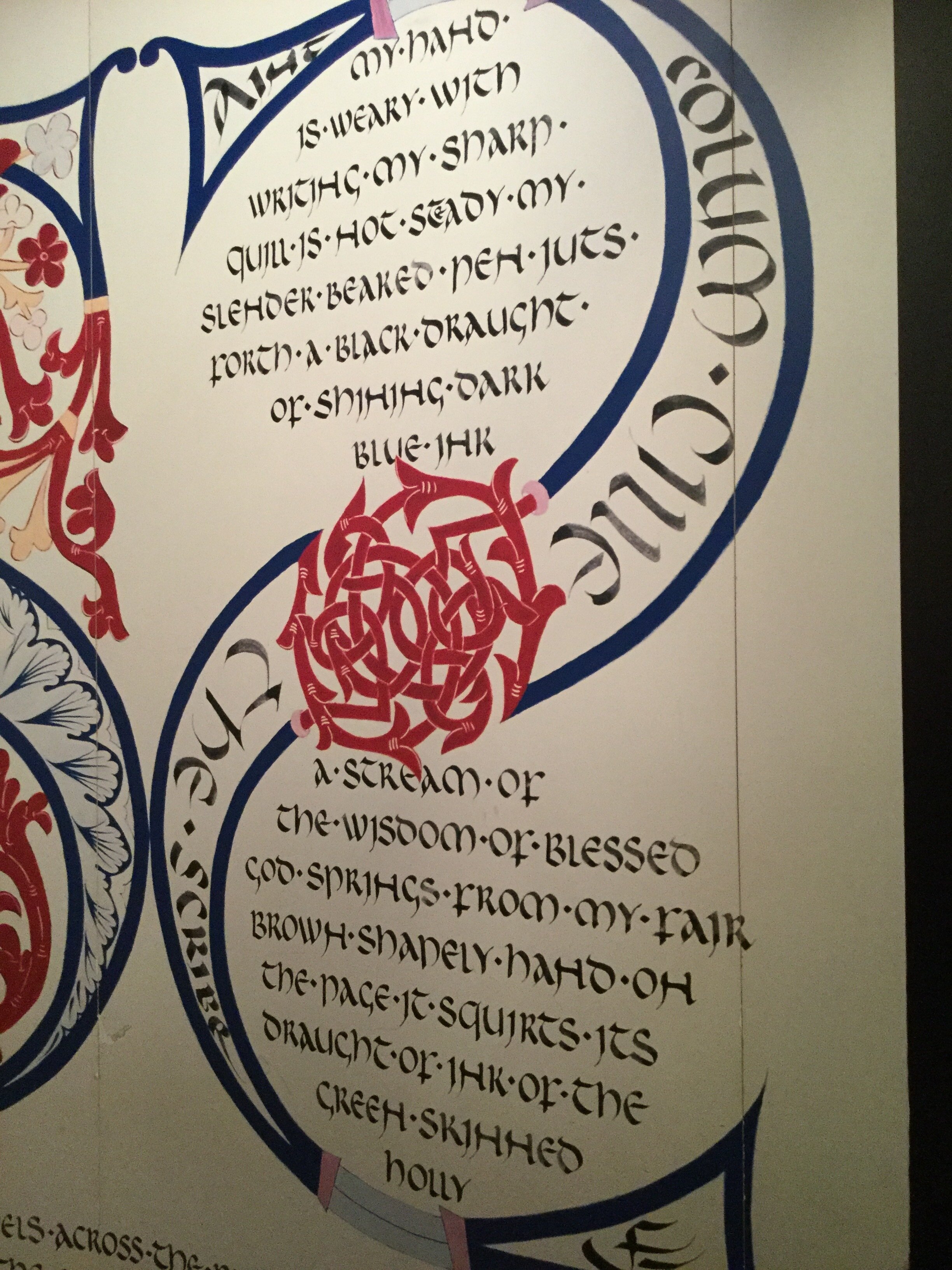

You see the stylized text here.

Poetic words as they would appear on the page.

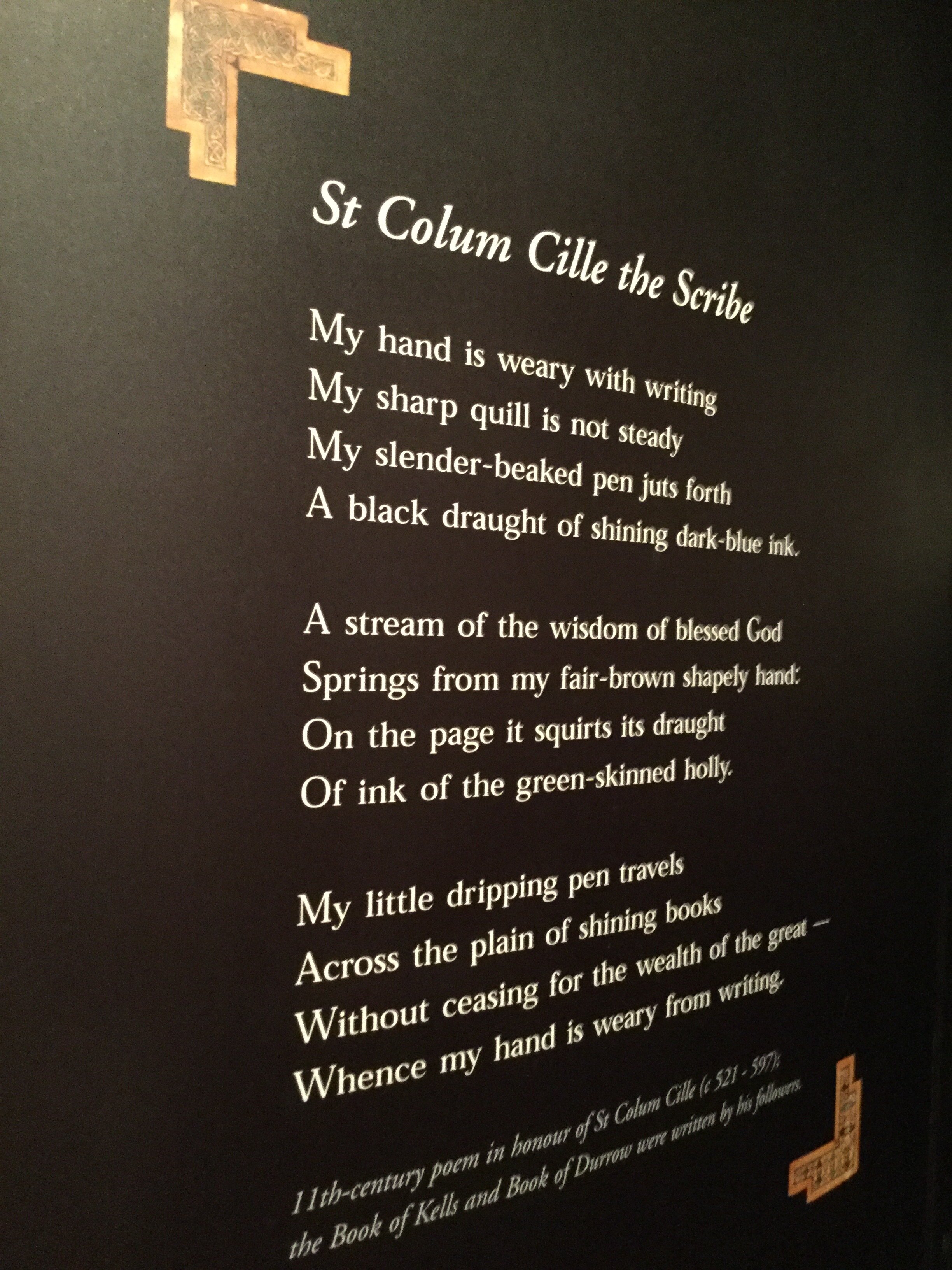

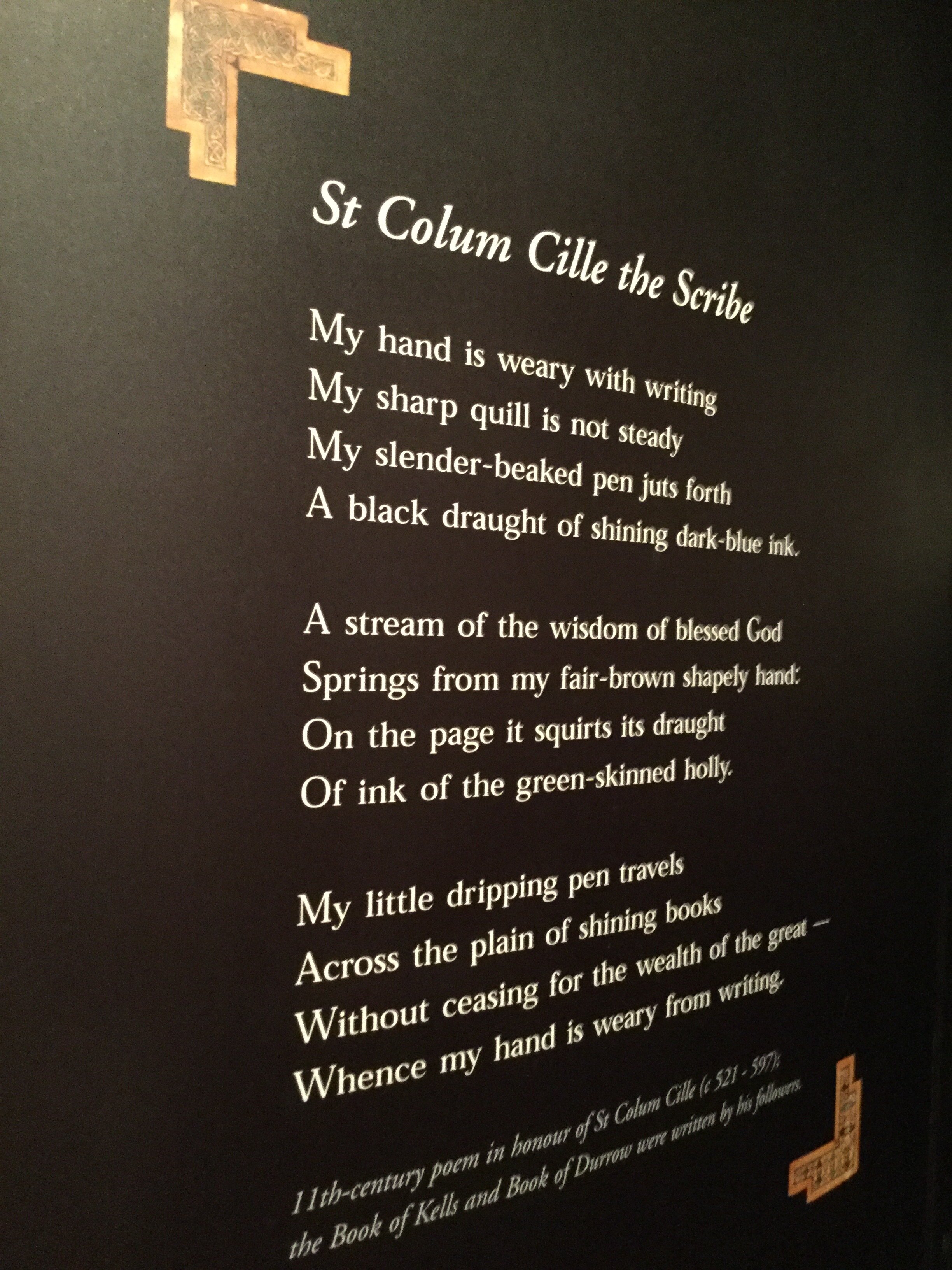

“11th-century poem in honour of St. Colum Cille (c521-597): the Book of Kells and Book of Durrow were written by his followers.”

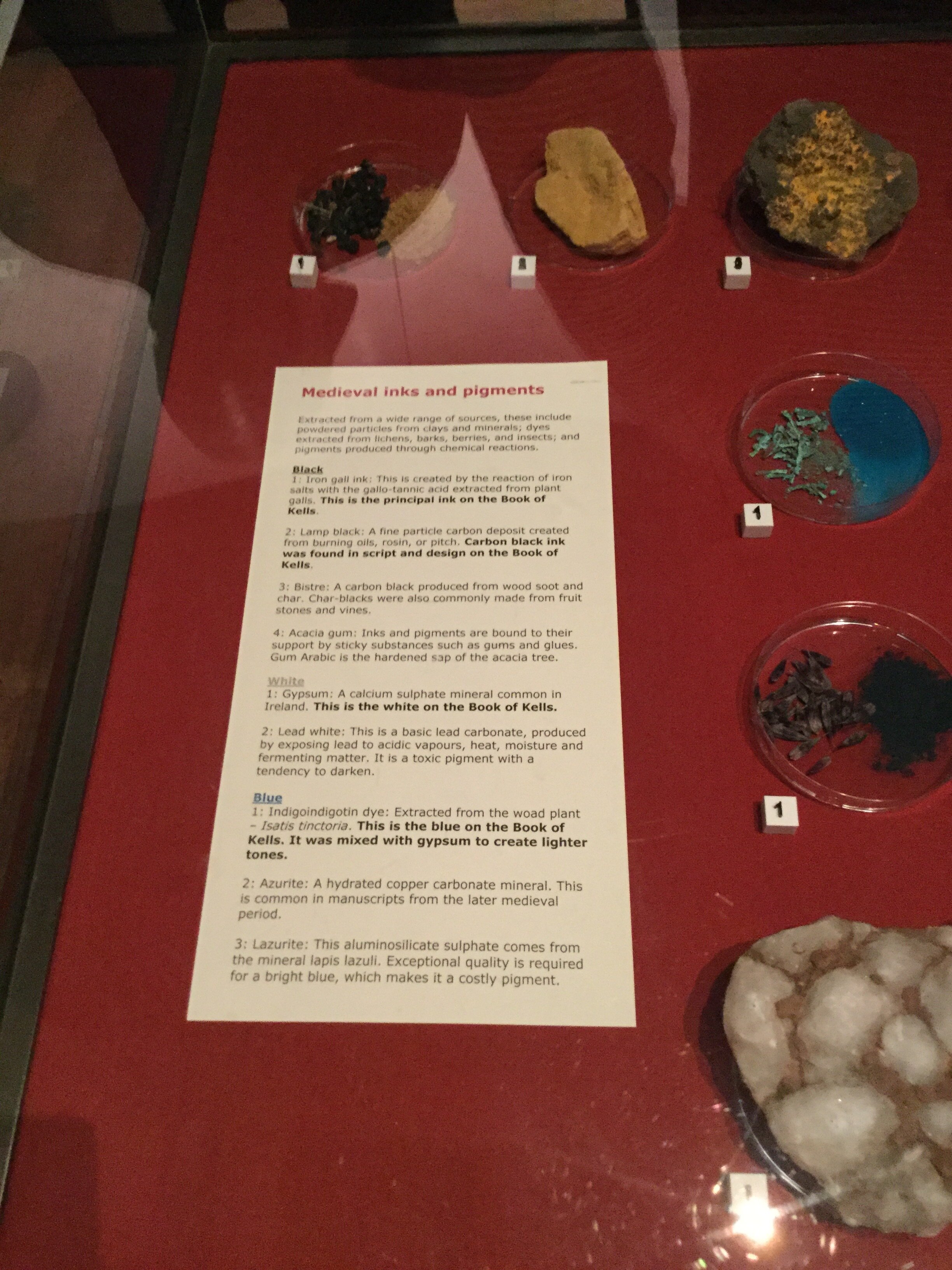

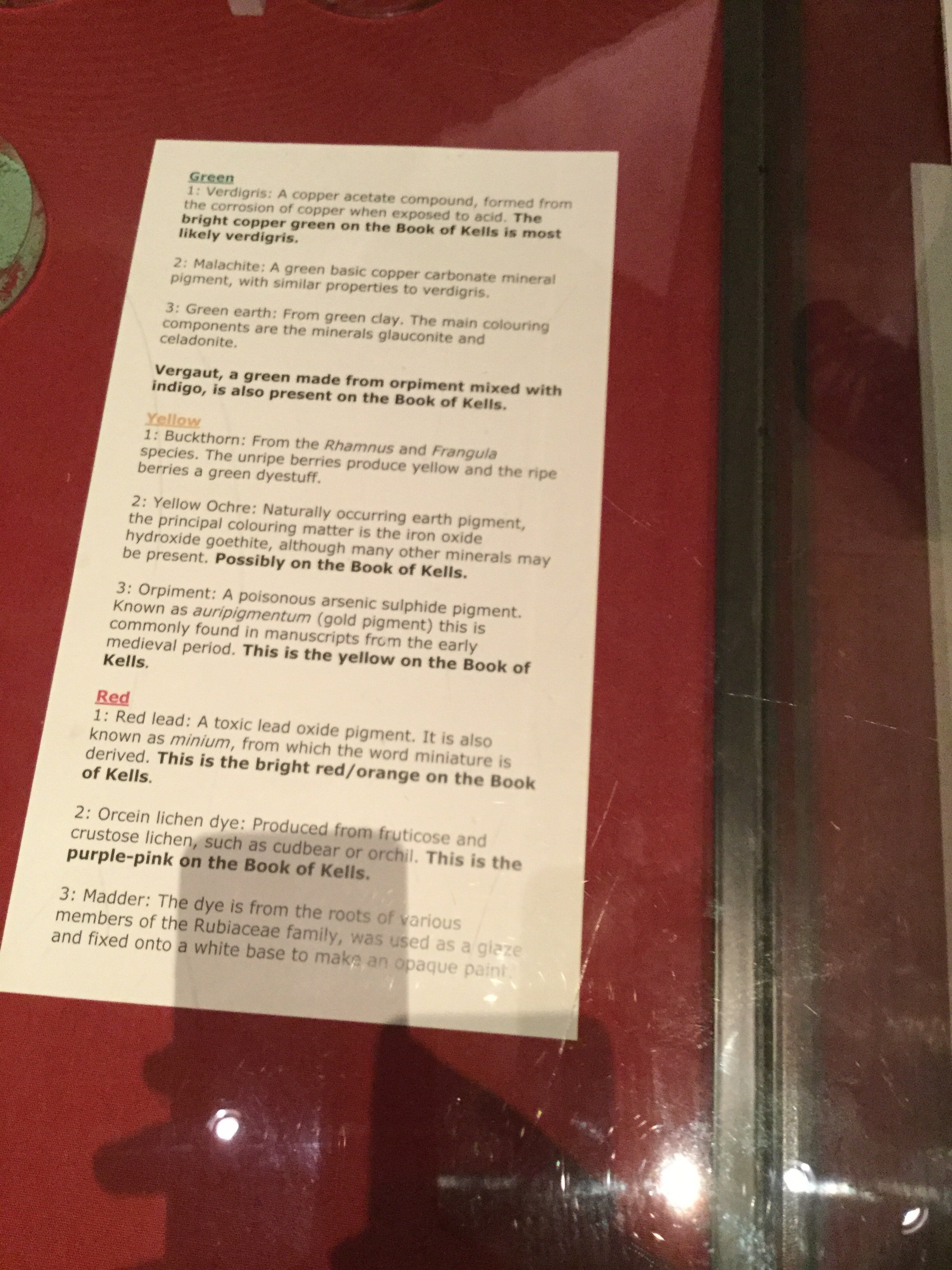

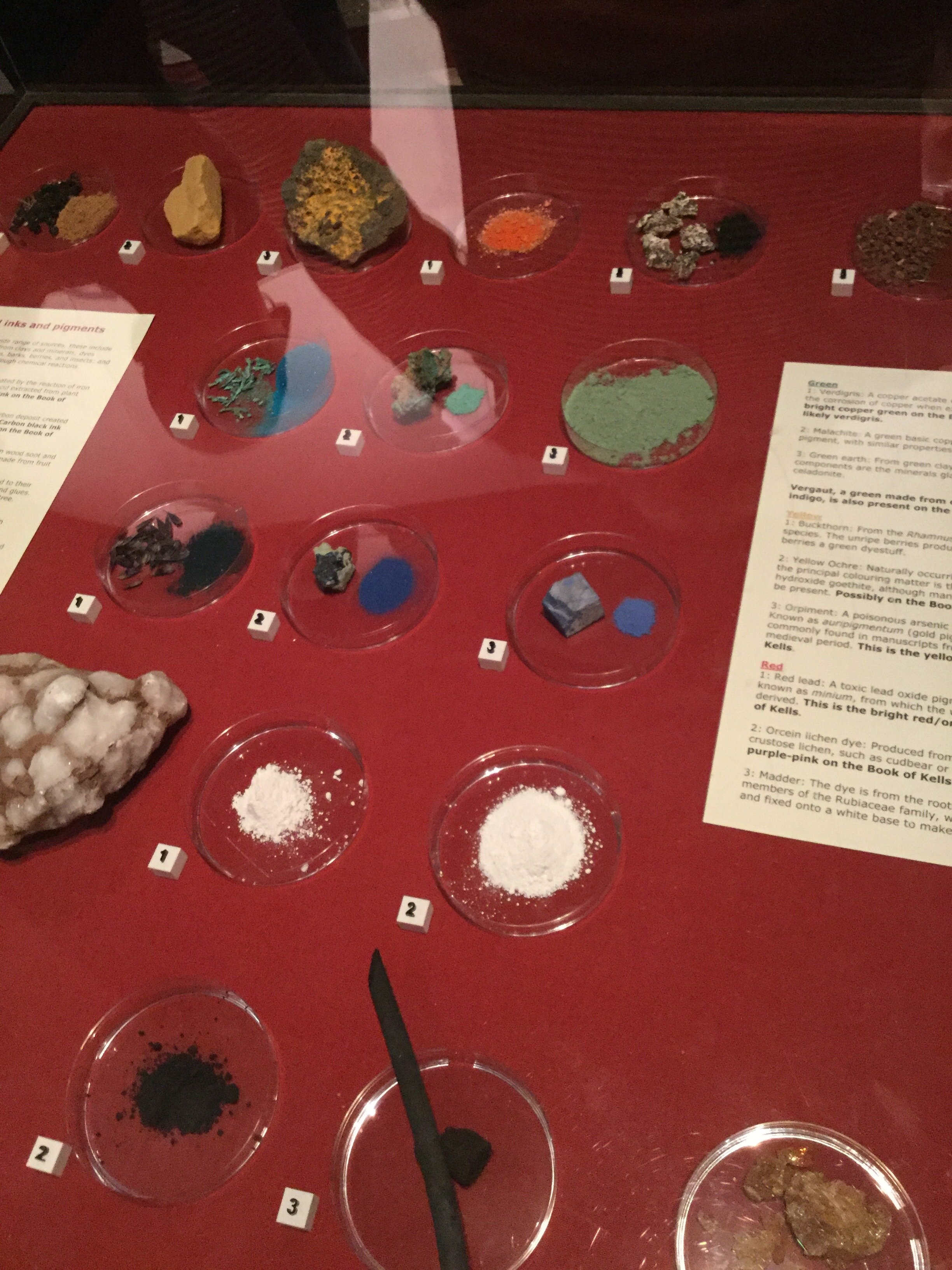

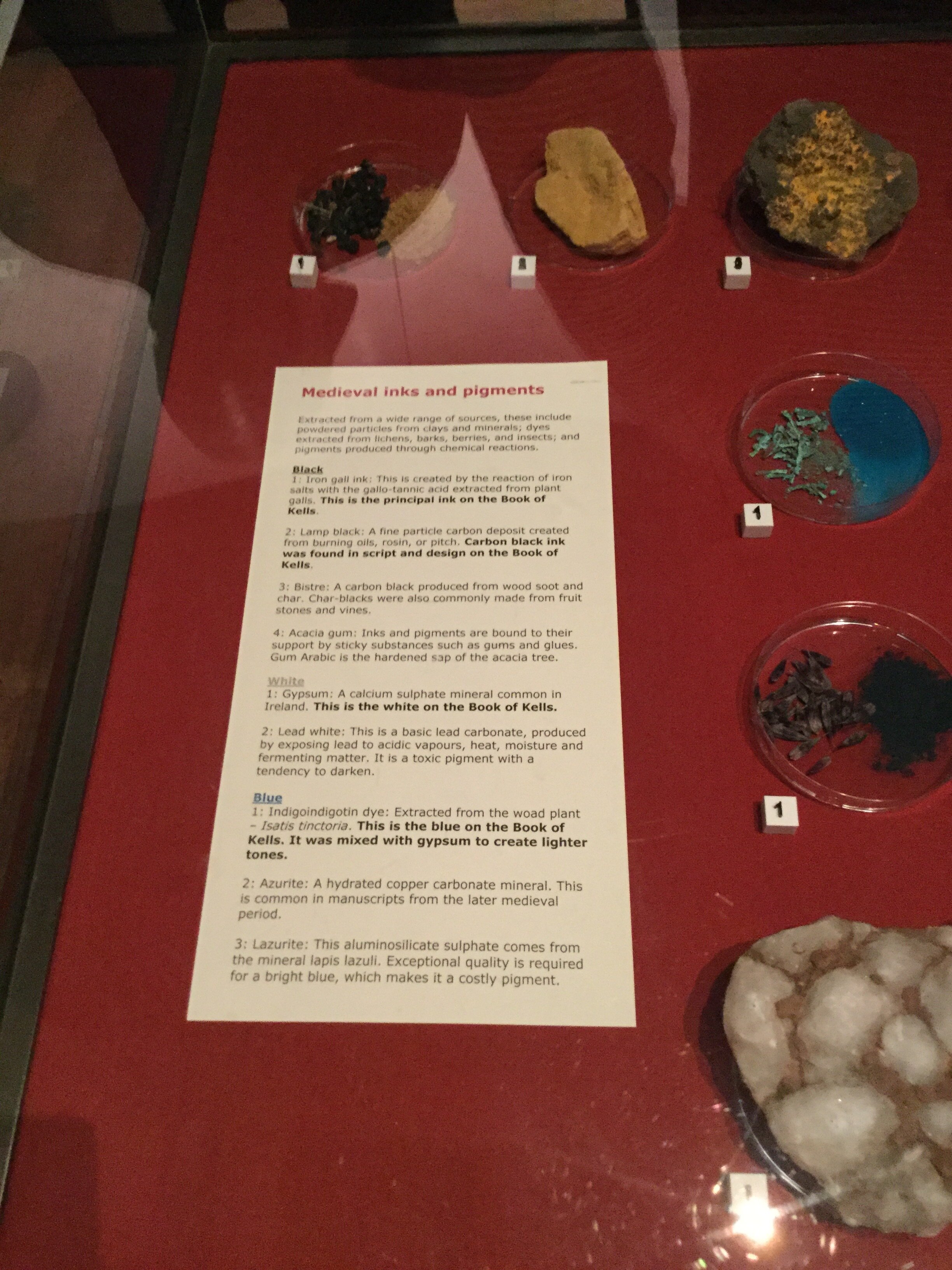

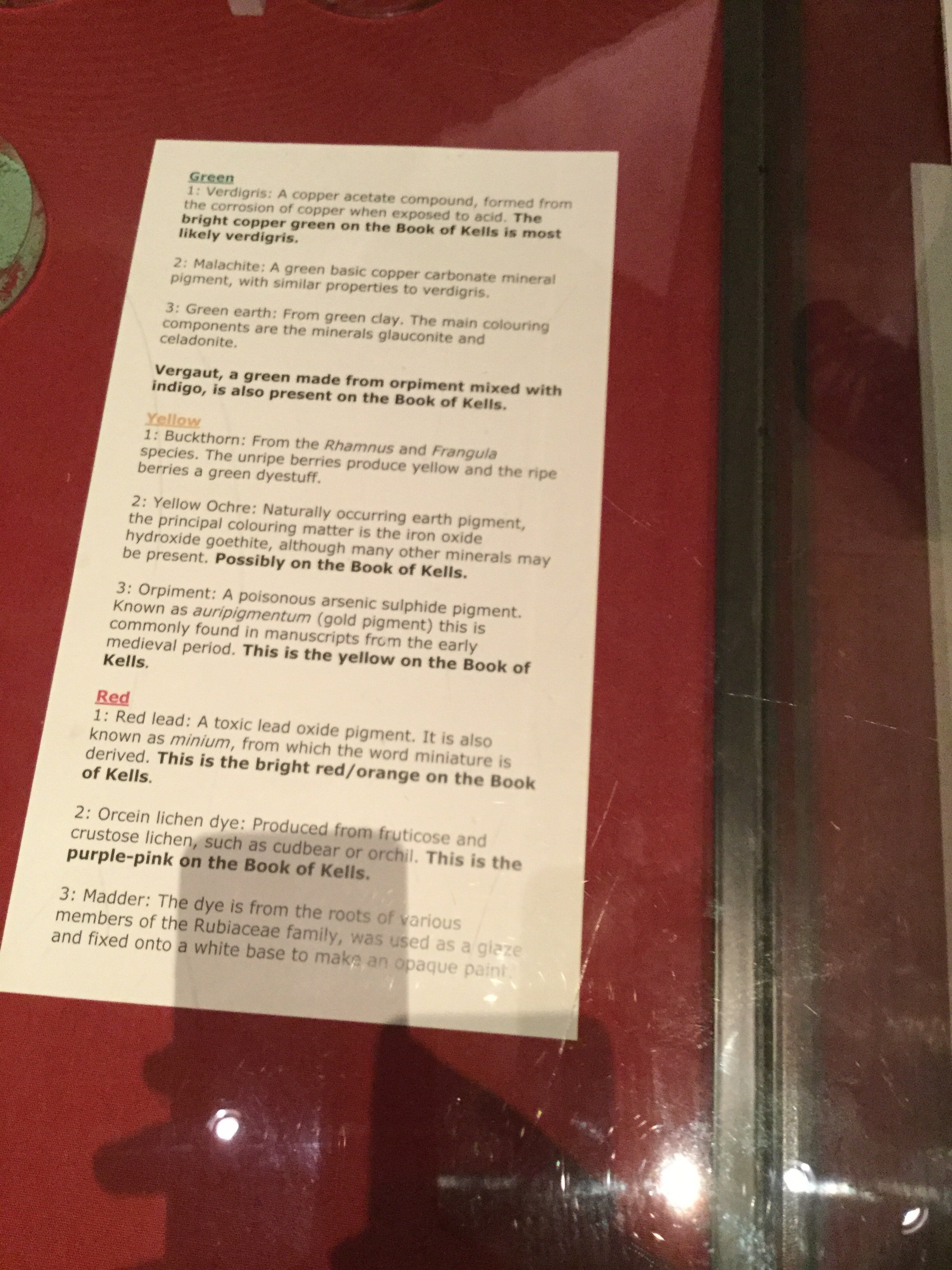

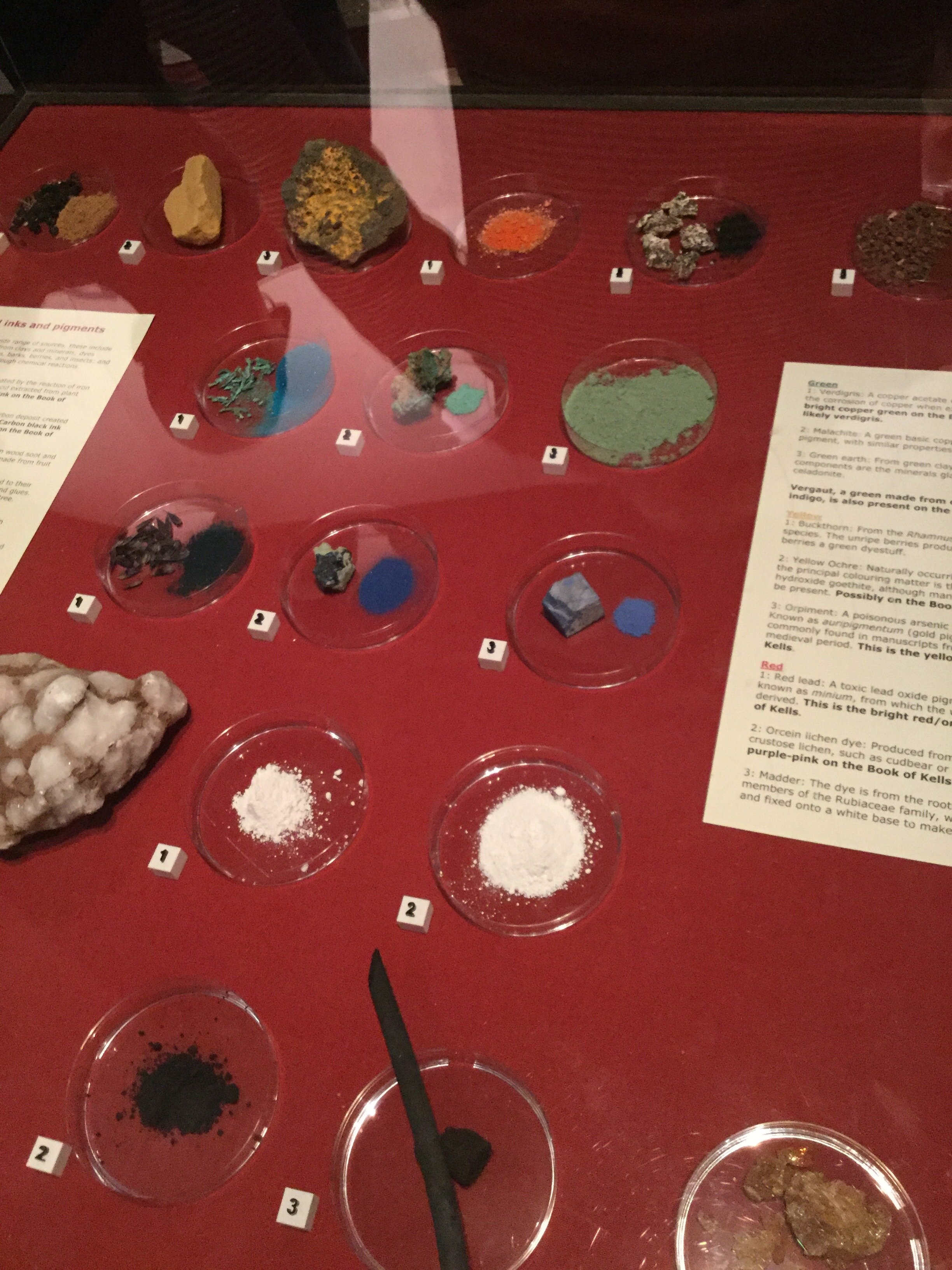

”Extracted from a wide range of sources, these include powdered particles from clays and minerals; dyes extracted from lichens, barks, berries, and insects; and pigments produced through chemical reactions.

Black

1: Iron gall ink: This is created by the reaction of iron salts with the gallo-tannic acid extracted from plant galls. This is the principal ink on the Book of Kells.

2: Lamp black: A fine particle carbon deposit created from burning oils, rosin, or pitch. Carbon black ink was found in script and design on the Book of Kells.

3: Bistre: A carbon black produced from wood soot and char. Char-blacks were also commonly made from fruit stones and vines.

4: Acacia gum: Inks and pigments are bound to their support by sticky substances such as gums and glues. Gum Arabic is the hardened sap of the acacia tree.

White

1: Gypsum: A calcium sulphate mineral common in Ireland. This is the white on the Book of Kells.

2: Lead white: This is a basic lead carbonate, produced by exposing lead to acidic vapours, heat, moisture and fermenting matter. It is a toxic pigment with a tendency to darken.

Blue

1: Indigoindigotin dye: Extracted from the woad plant - Isatis tinctoria. This is the blue on the Book of Kells. It was mixed with gypsum to create lighter tones.

2: Azurite: A hydrated copper carbonate mineral. This is common in manuscripts from the later medieval period.

3: Lazurite: This aluminosilicate sulphate comes from the mineral lapis lazuli. Exceptional quality is required for a bright blue, which makes it a costly pigment.”

Green

1: Verdigris: A copper acetate compound, formed from the corrosion of copper when exposed to acid. The bright copper green on the Book of Kells is most likely verdigris.

2: Malachite: A green basic copper carbonate mineral pigment, with similar properties to verdigris.

3: Green earth: From green clay. The main colouring components are the minerals glauconite and celadonite.

Vergaut, a green made from orpiment mixed with indigo, is also present on the Book of Kells.

Yellow

1: Buckthorn: From the Rhamnus and Frangula species. The unripe berries produce yellow and the ripe berries a green dyestuff.

2: Yellow Ochre: Naturally occurring earth pigment, the principal colouring matter is the iron oxide hydroxide goethite, although many other minerals may be present. Possibly on the Book of Kells.

3: Orpiment: A poisonous arsenic sulphide pigment. Known as auripigmentum (gold pigment) this is commonly found in manuscripts from the early medieval period. This is the yellow on the Book of Kells.

Red

1: Red lead: A toxic lead oxide pigment. It is also known as minium, from which the word miniature is derived. This is the bright red/orange on the Book of Kells.

2: Orcein lichen dye: Produced from fruticose and crustose lichen, such as cudbear or orchil. This is the purple-pink on the Book of Kells.

3: Madder: The dye is from the roots of various members of the Rubiaceae family, was used as a glaze and fixed onto a white base to make an opaque paint."

Medieval inks and pigments

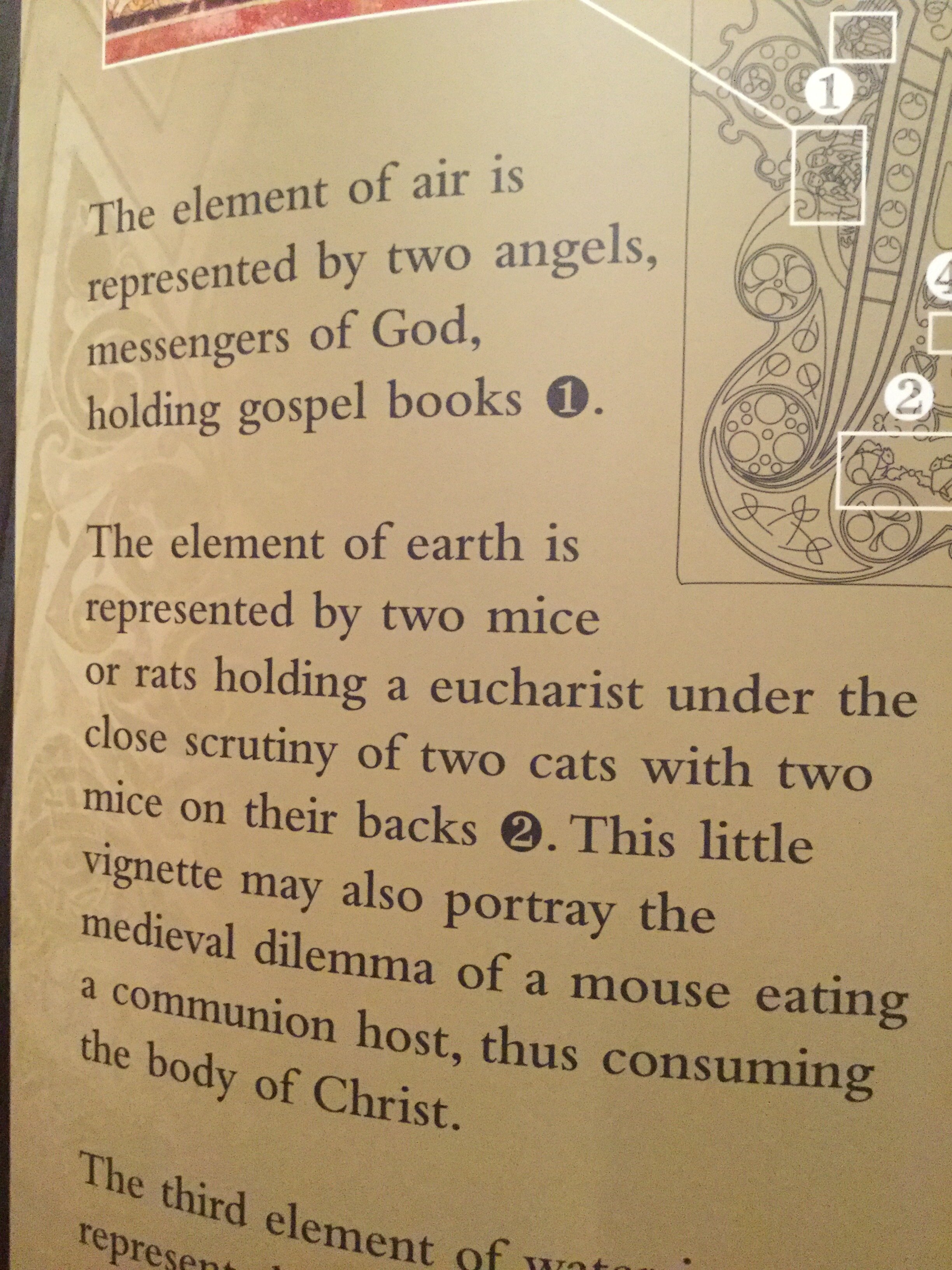

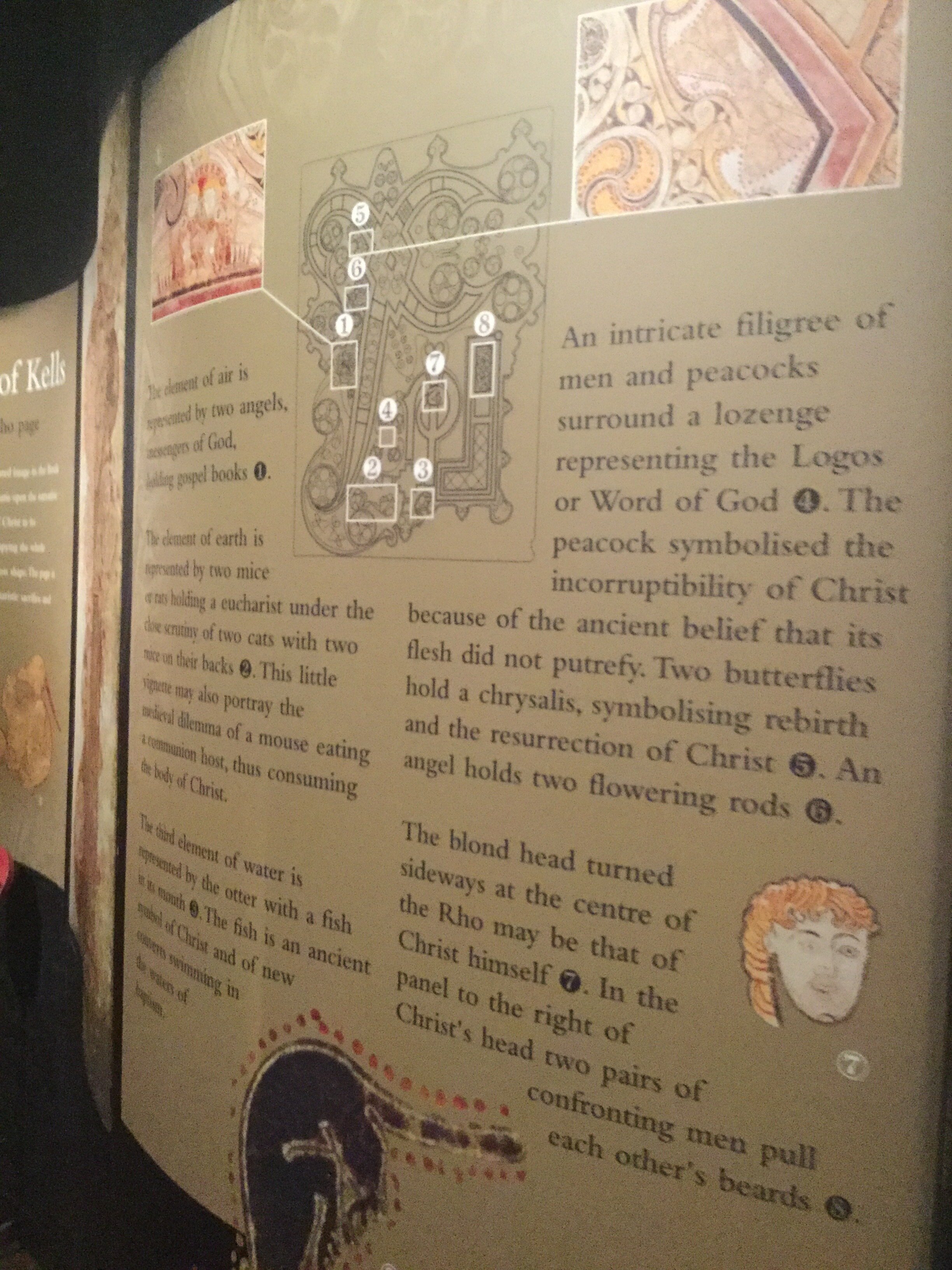

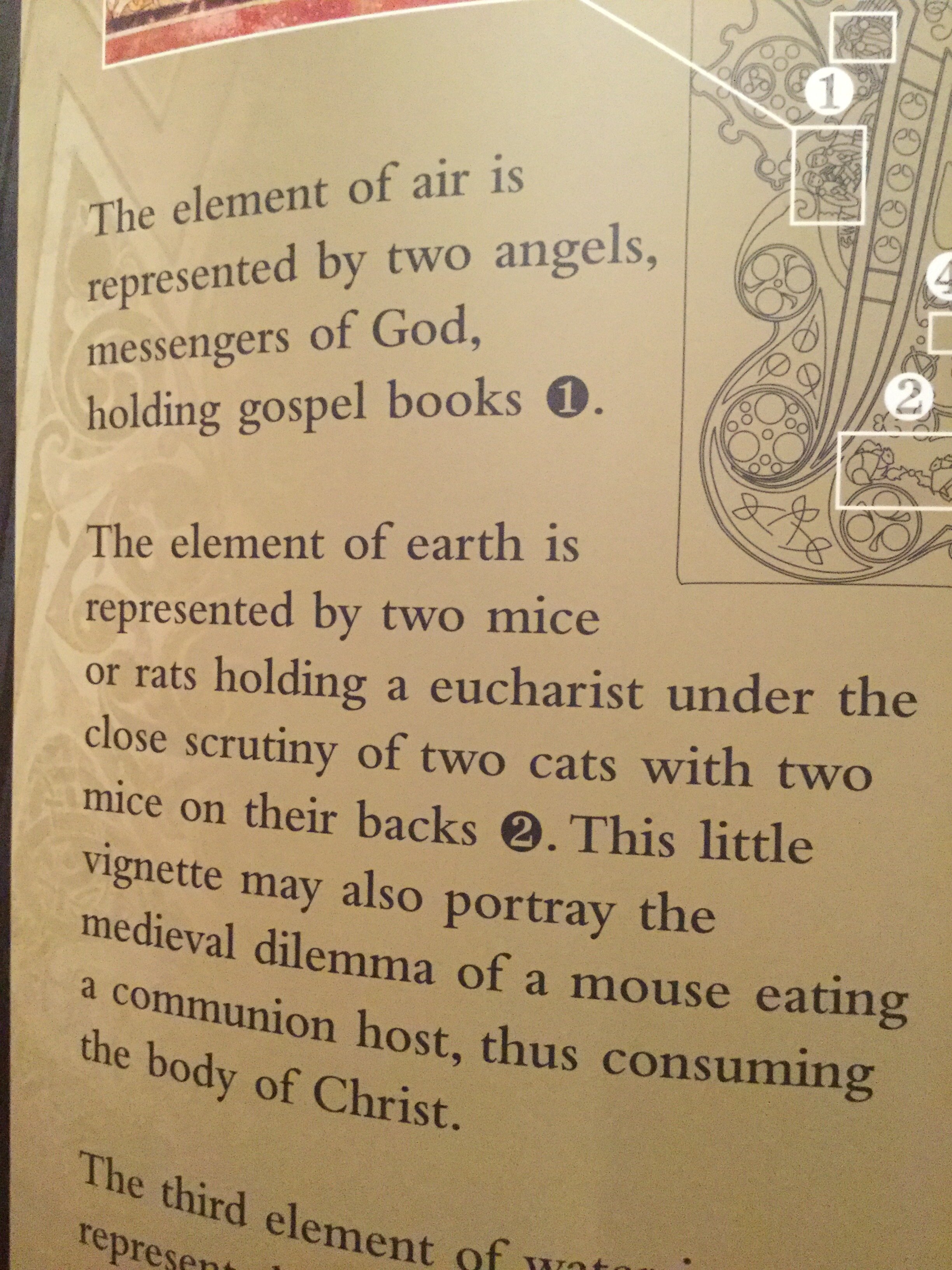

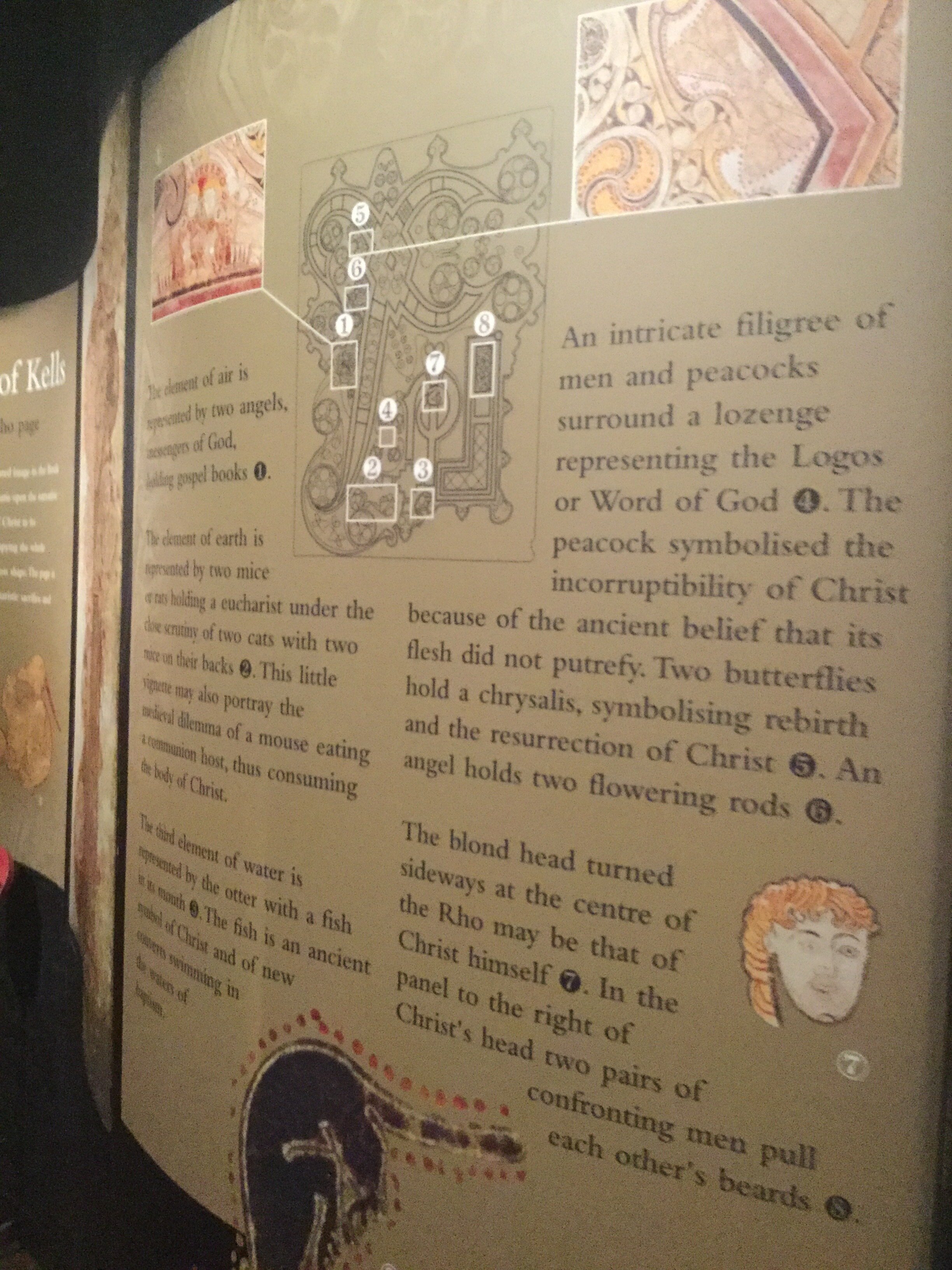

"The element of air is represented by two angels, messengers of God, holding gospel books.

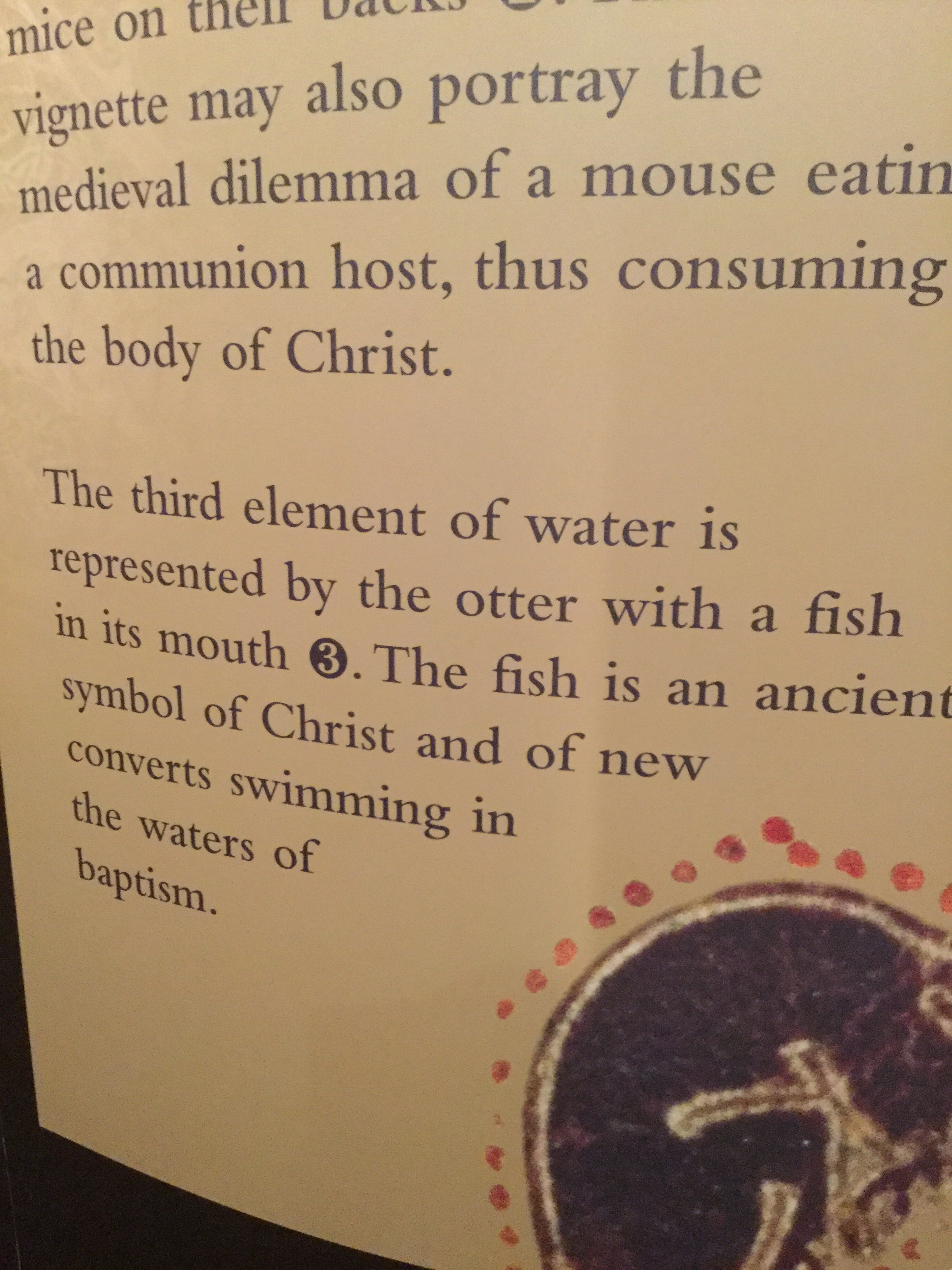

The element of earth is represented by two mice or rats holding a eucharist under the close scrutiny of two cats with two mice on their backs. This little vignette may also portray the medieval dilemma of a mouse eating a communion host, thus consuming the body of Christ."

"The third element of water is represented by the otter with a fish in its mouth. This fish is an ancient symbol of Christ and of new converts swimming in the waters of baptism."

“An intricate filigree of men and peacocks surround a lozenge representing the Logos or Word of God. The peacock symbolised the incorruptibility of Christ because of the ancient belief that its flesh did not putrefy. Two butterflies hold a chrysalis, symbolising rebirth and the resurrection of Christ. An angel holds two flowering rods.

The blond head turned sideways at the centre of the Rho may be that of Christ himself. In the panel to the right of Christ’s head two pairs of confronting men pull each other’s beards.”

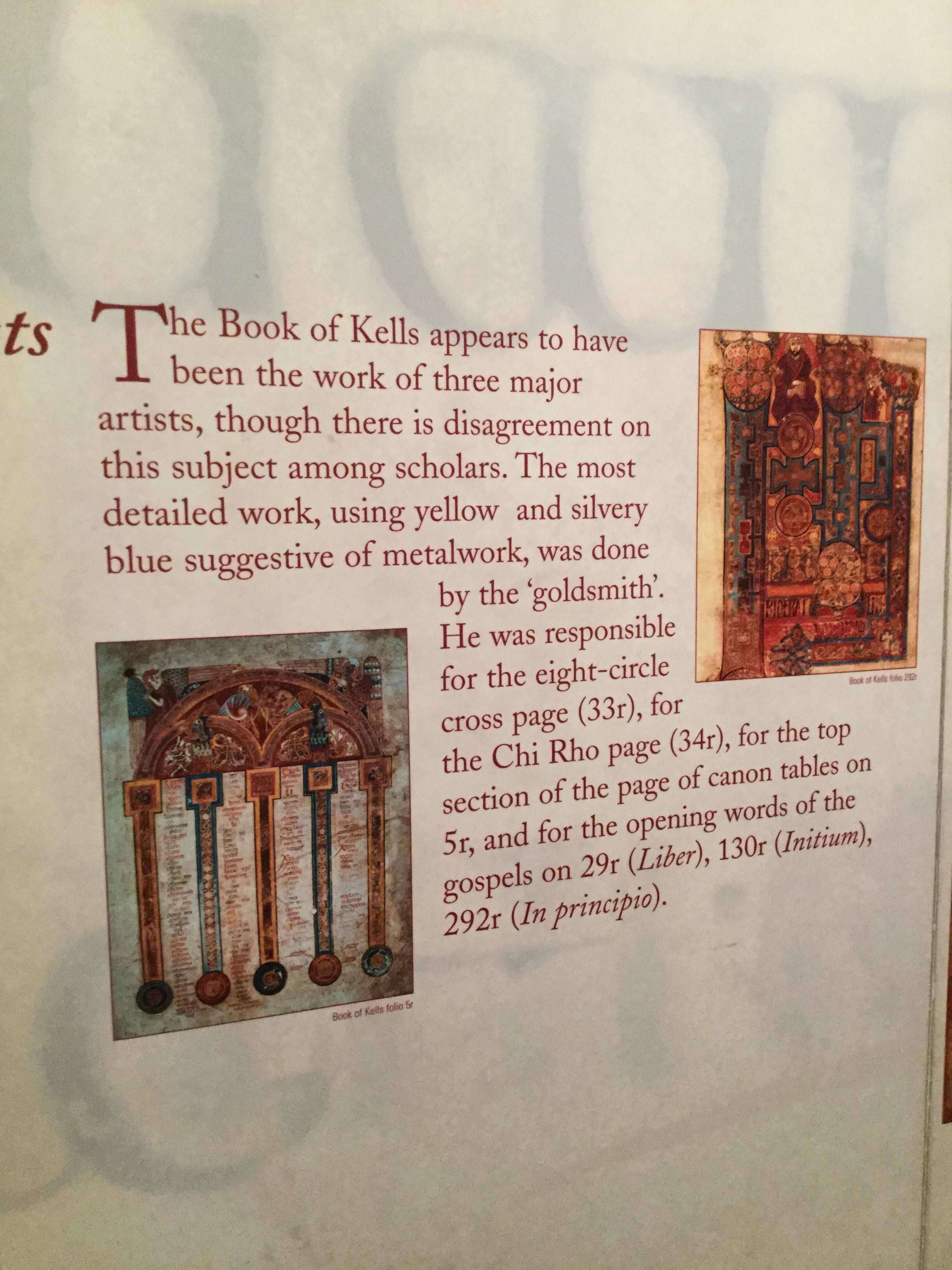

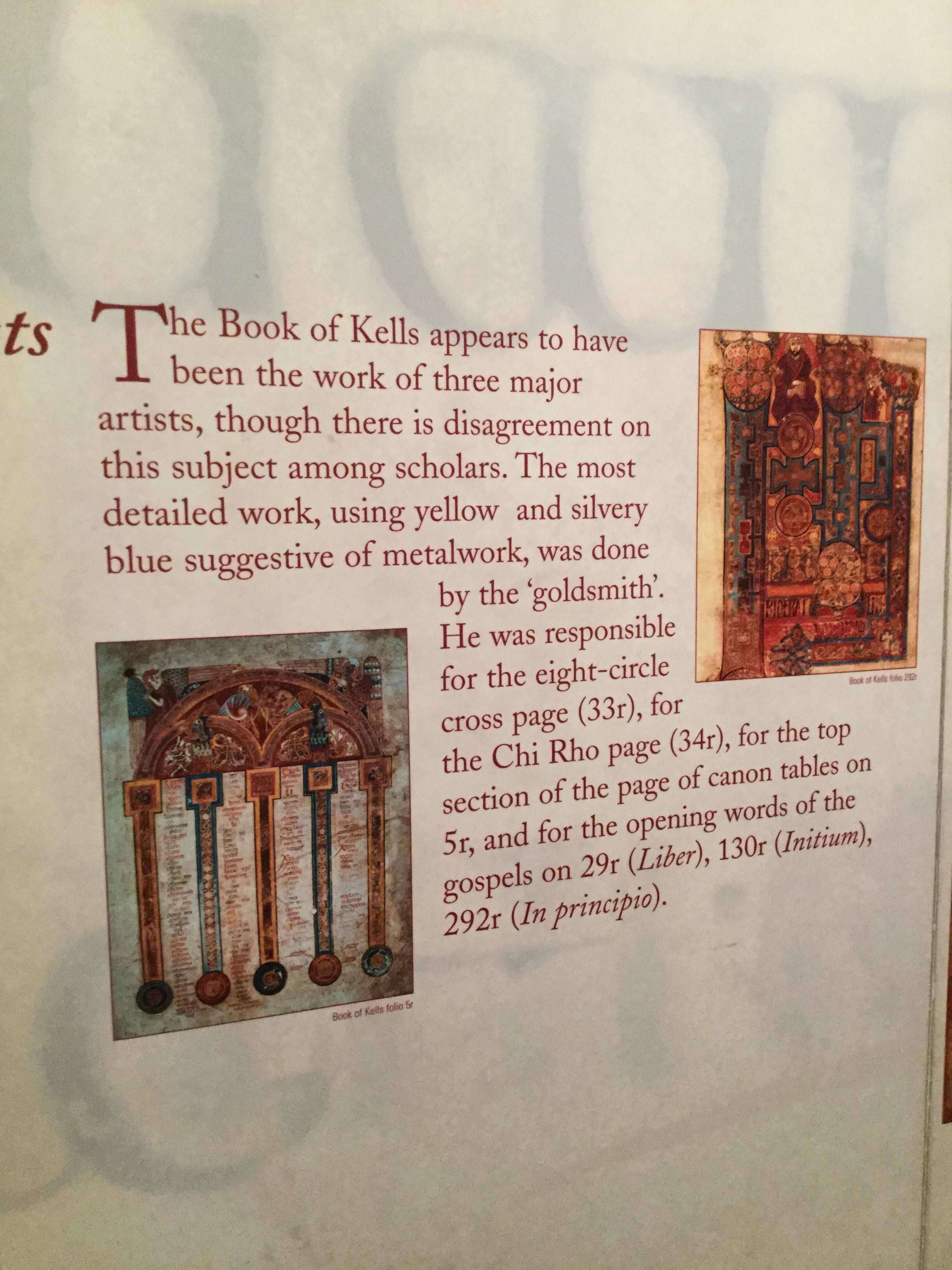

"The Book of Kells appears to have been the work of three major artists, though there is disagreement on this subject among scholars. The most detailed work, using yellow and silvery blue suggestive of metalwork, was done by the 'goldsmith'. He was responsible for the eight-circle cross page (33r), for the Chi Rho page (34r), for the top section of the page of canon tables on 5r, and for the opening words of the gospels on 29r (Liber), 130r (Initium), 292r (In principio)."

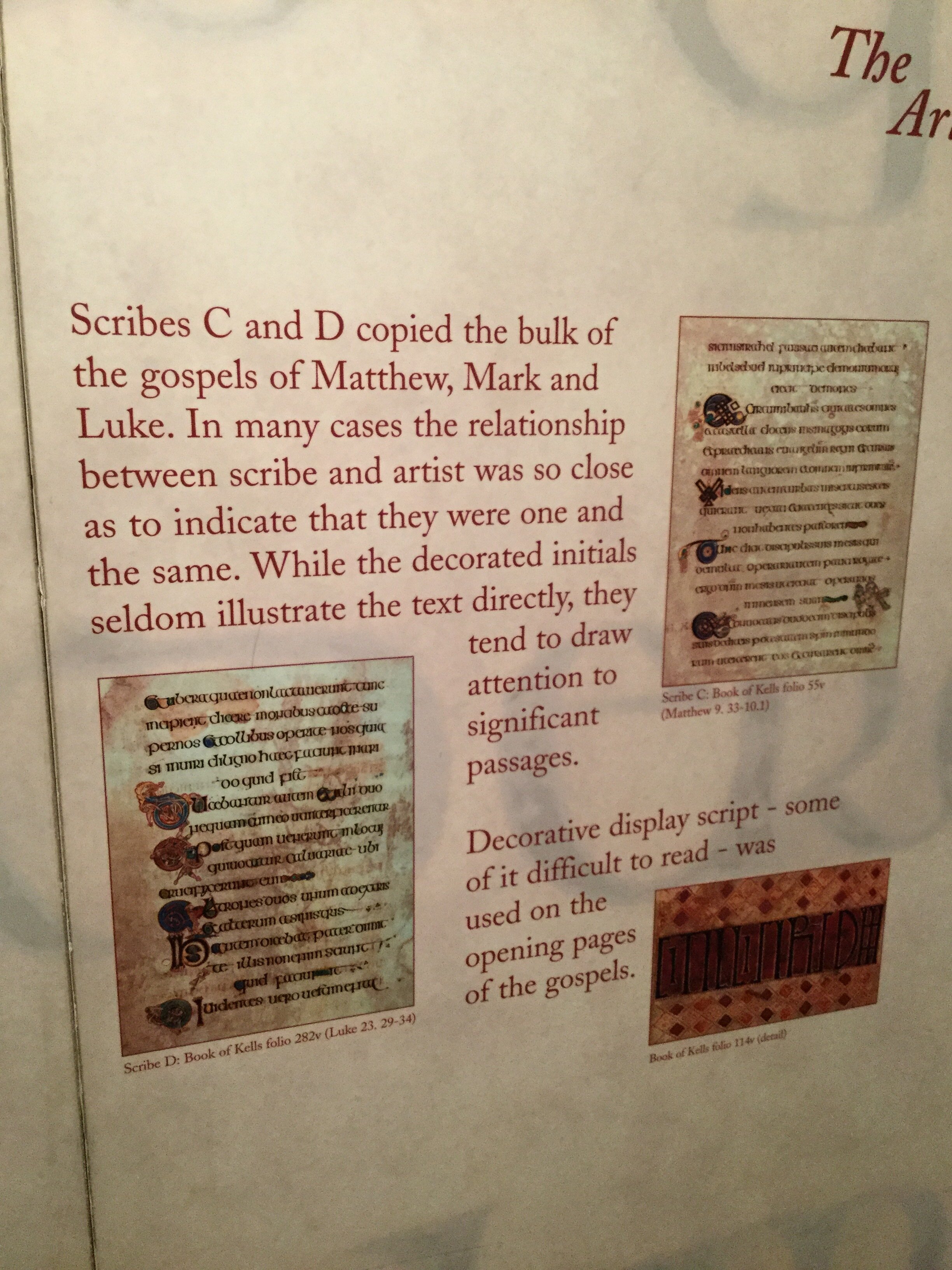

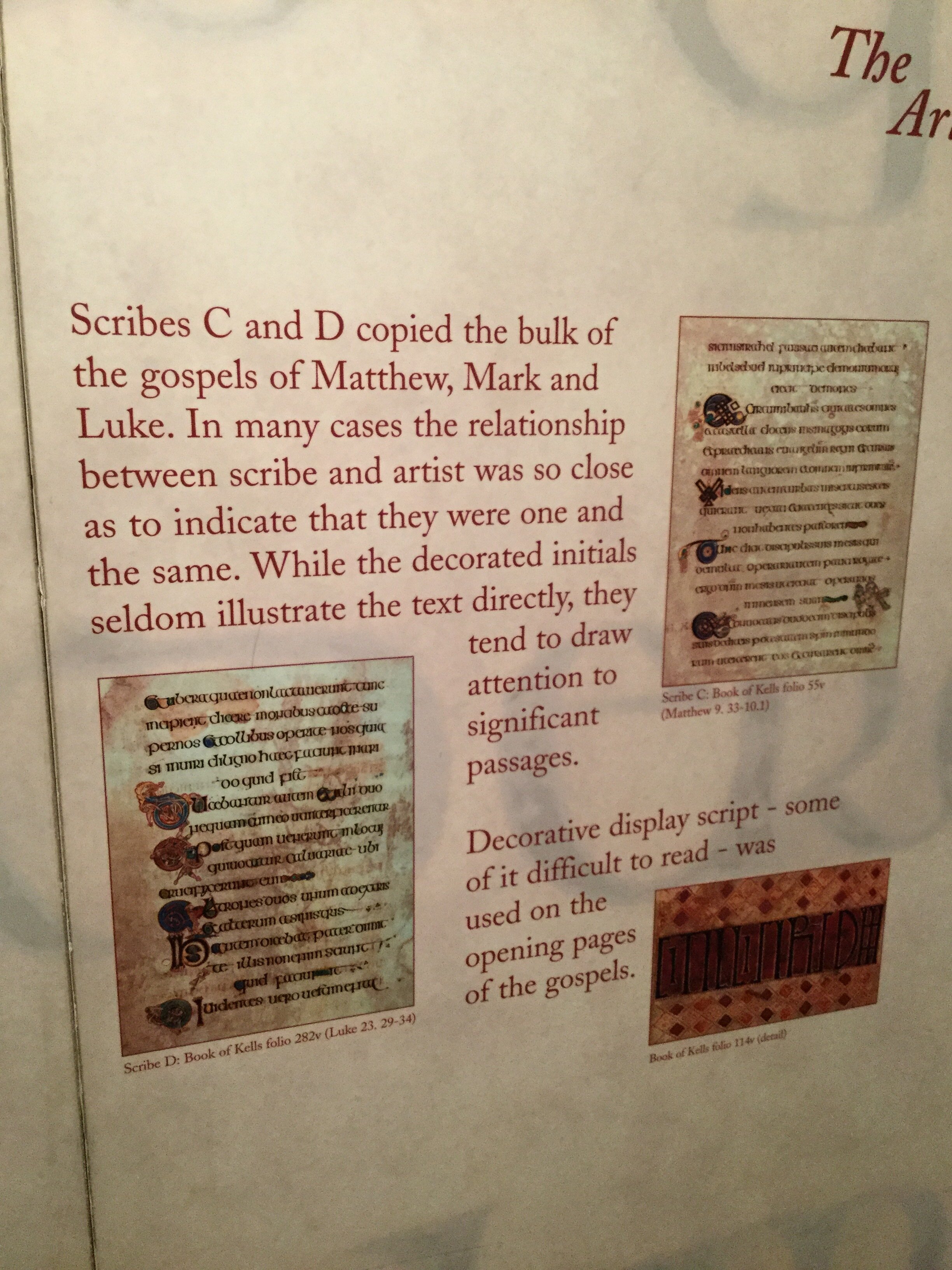

"Scribes C and D copied the bulk of the gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke. In many cases the relationship between scribe and artist was so close as to indicate that they were one and the same. While the decorated initials seldom illustrate the text directly, they tend to draw attention to significant passages.

Decorative display script - some of it difficult to read - was used on the opening pages of the gospels."

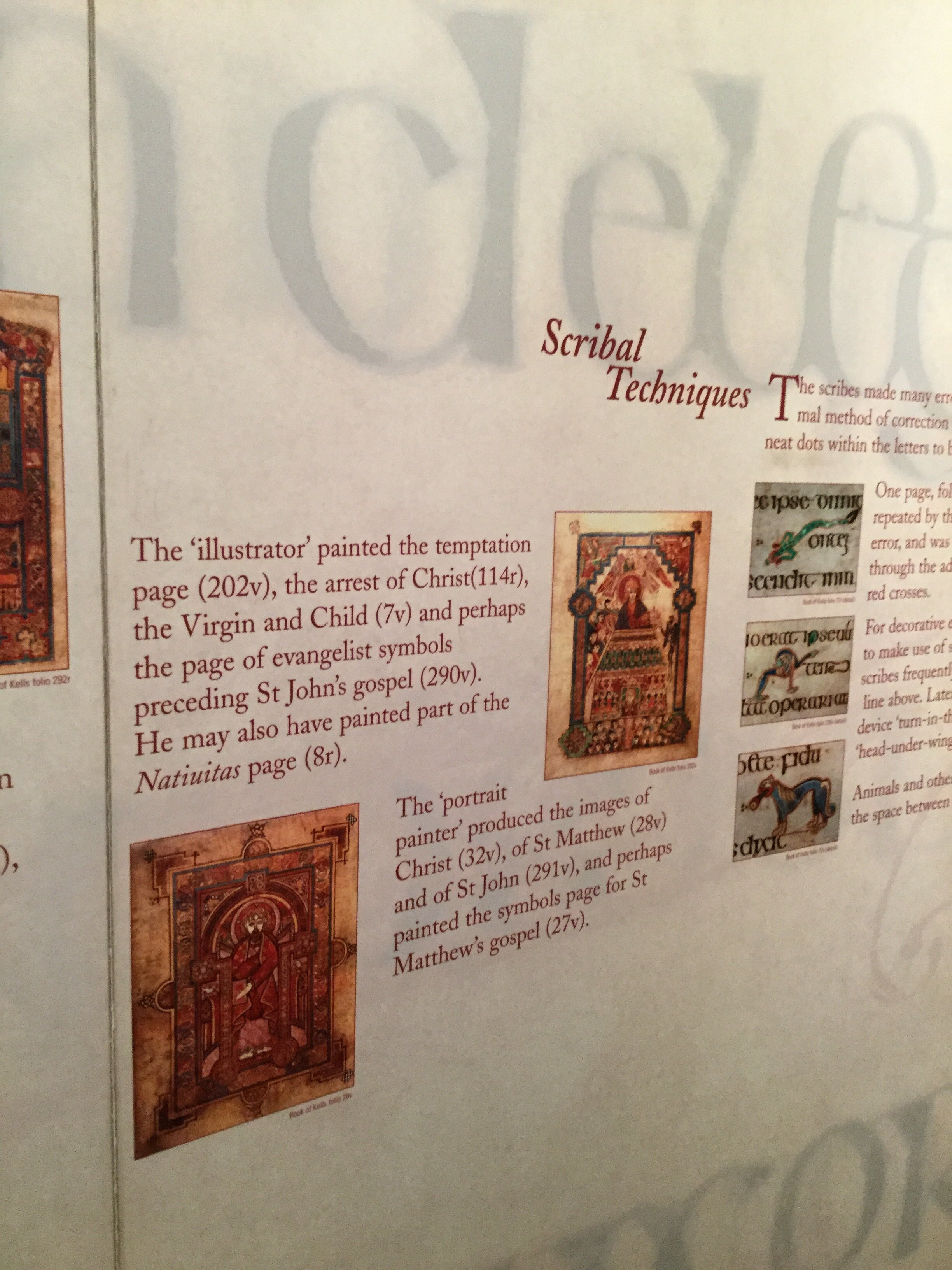

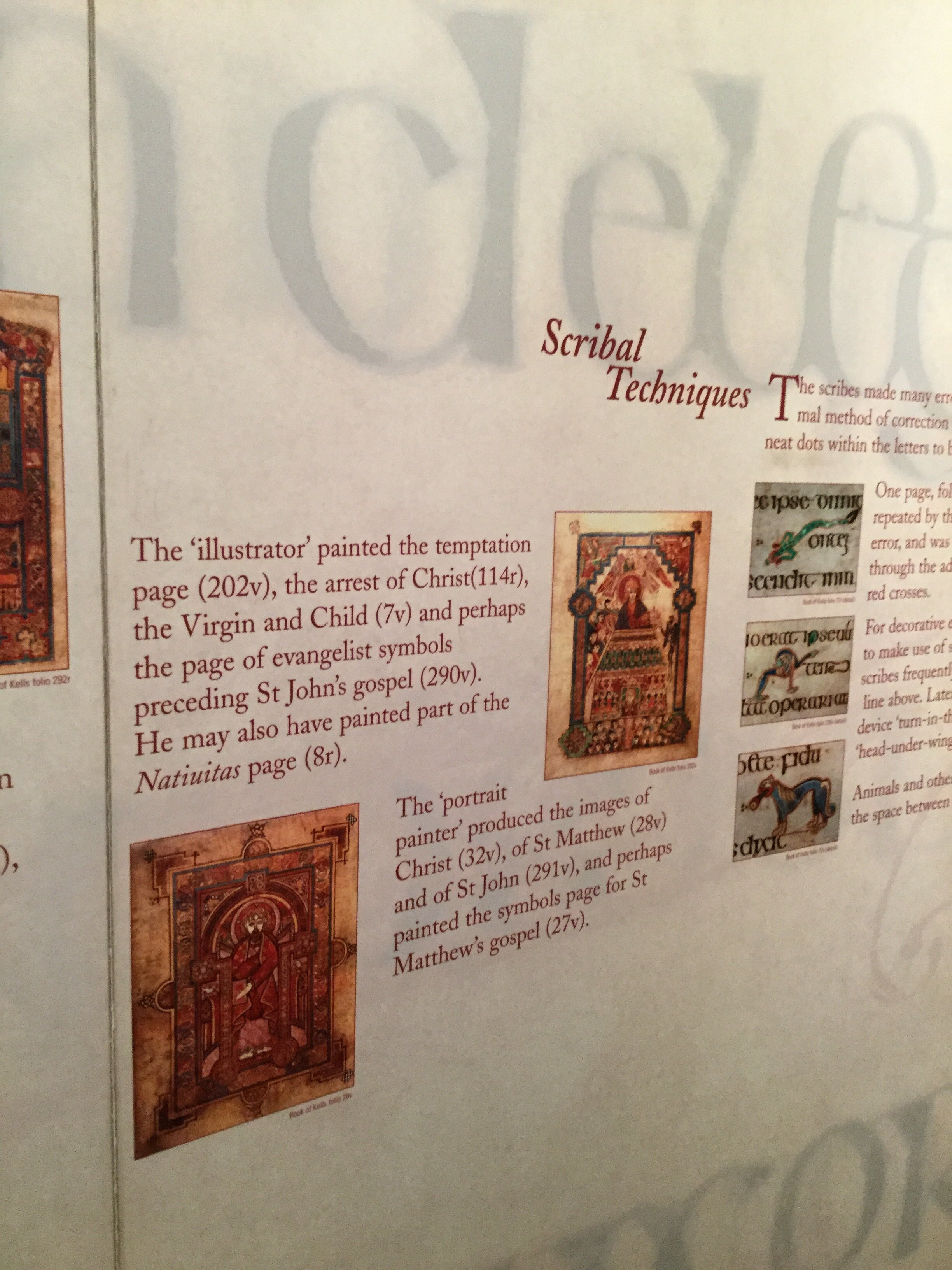

“The 'illustrator' painted the temptation page (202v), the arrest of Christ (114r), the Virgin and Child (7v) and perhaps the page of evangelist symbols preceding St. John's gospel (290v). He may also have painted part of the Natiuitas page (8r).

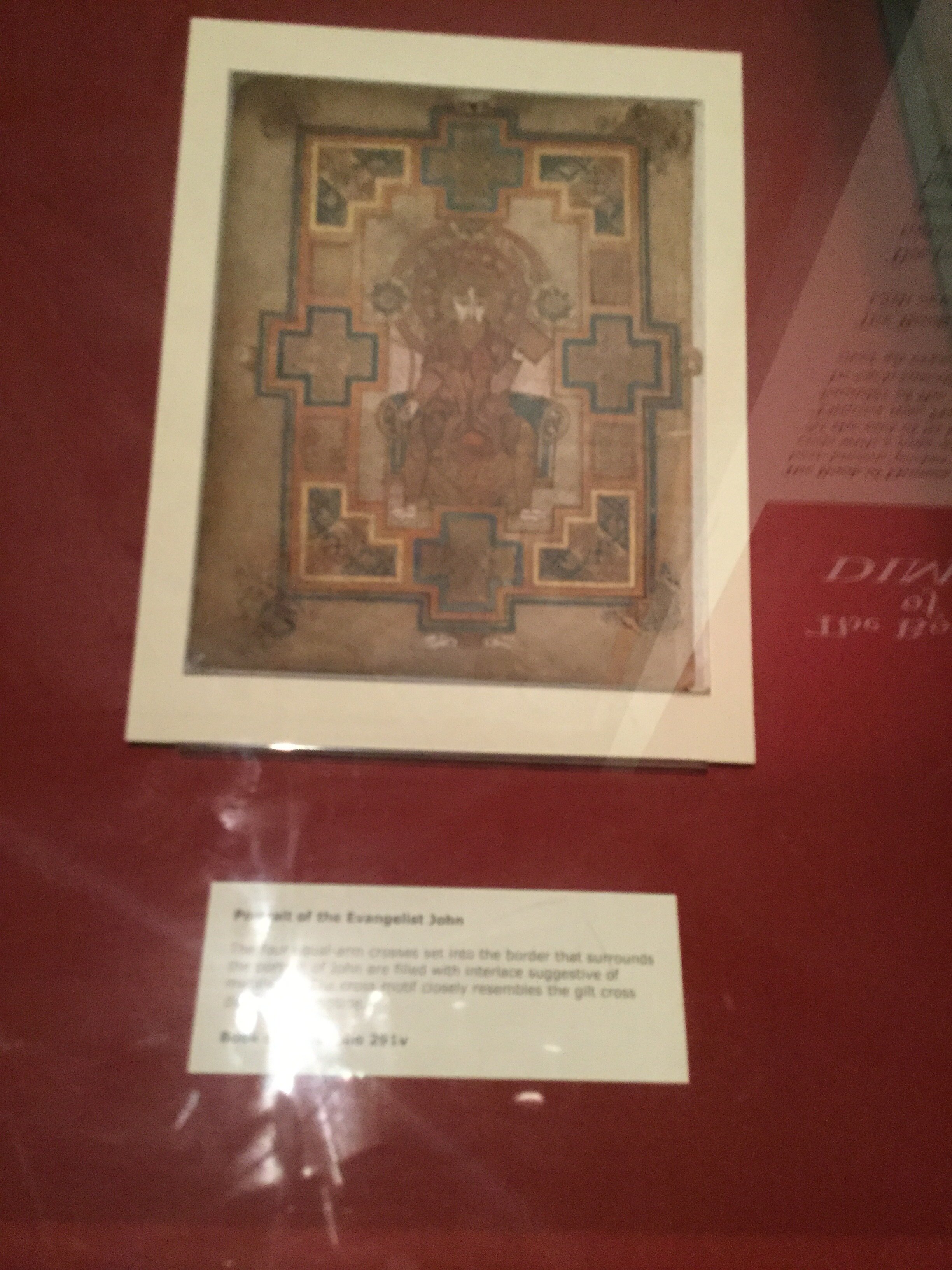

The 'portrait painter' produced the images of Christ (32v), of St. Matthew (28v) and of St. John (291v), and perhaps painted the symbols page for St. Matthew's gospel (27v)."

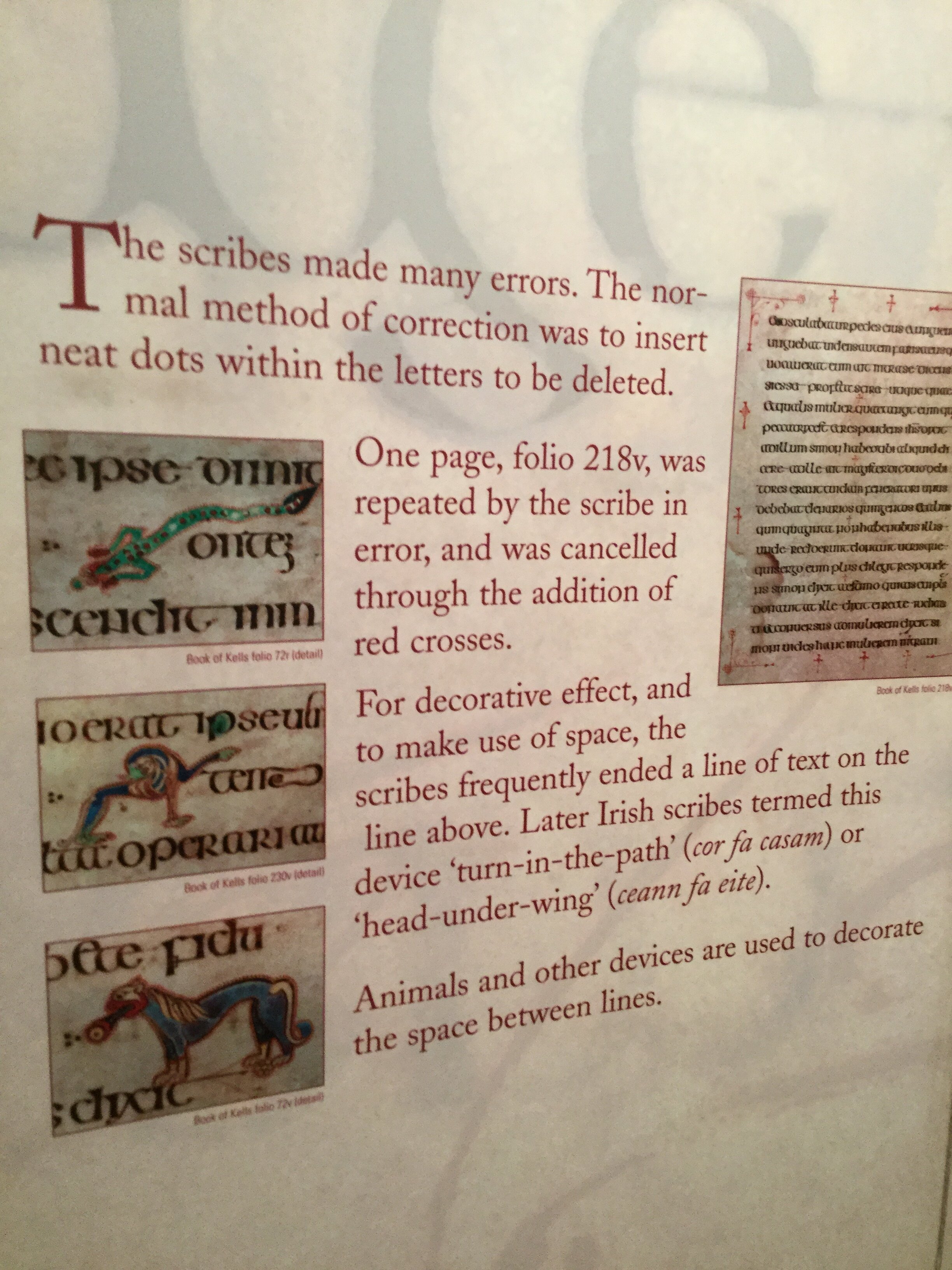

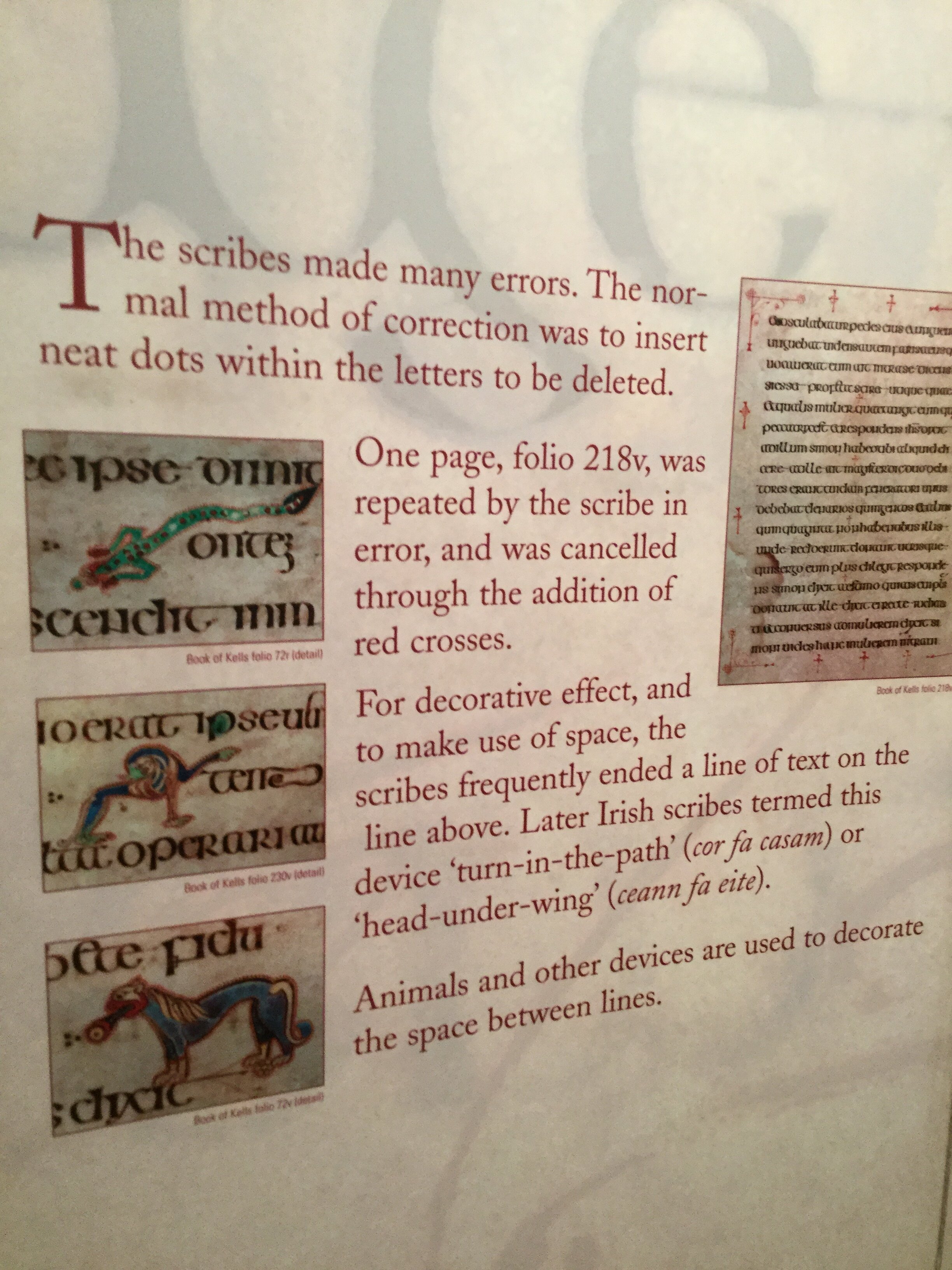

"The scribes made many errors. The normal method of correction was to insert neat dots within the letters to be deleted.

One page, folio 218v, was repeated by the scribe in error, and was cancelled through the addition of red crosses.

For decorative effect, and to make use of space, the scribes frequently ended a line of text on the line above. Later Irish scribes termed this device 'turn-in-the-path' (cor fa casam) or 'head-under-wing' (ceann fa eite).

Animals and other devices are used to decorate the space between lines."

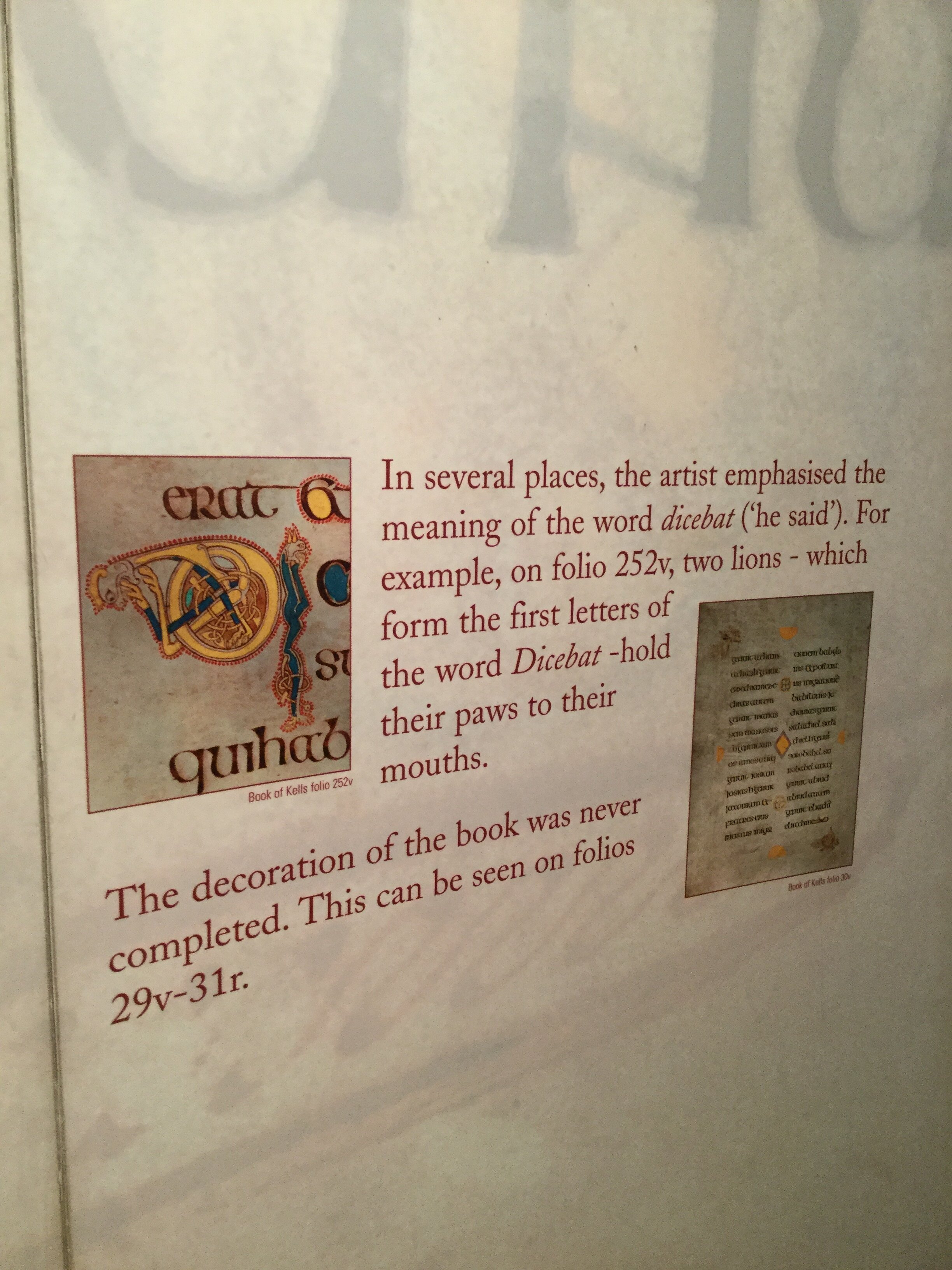

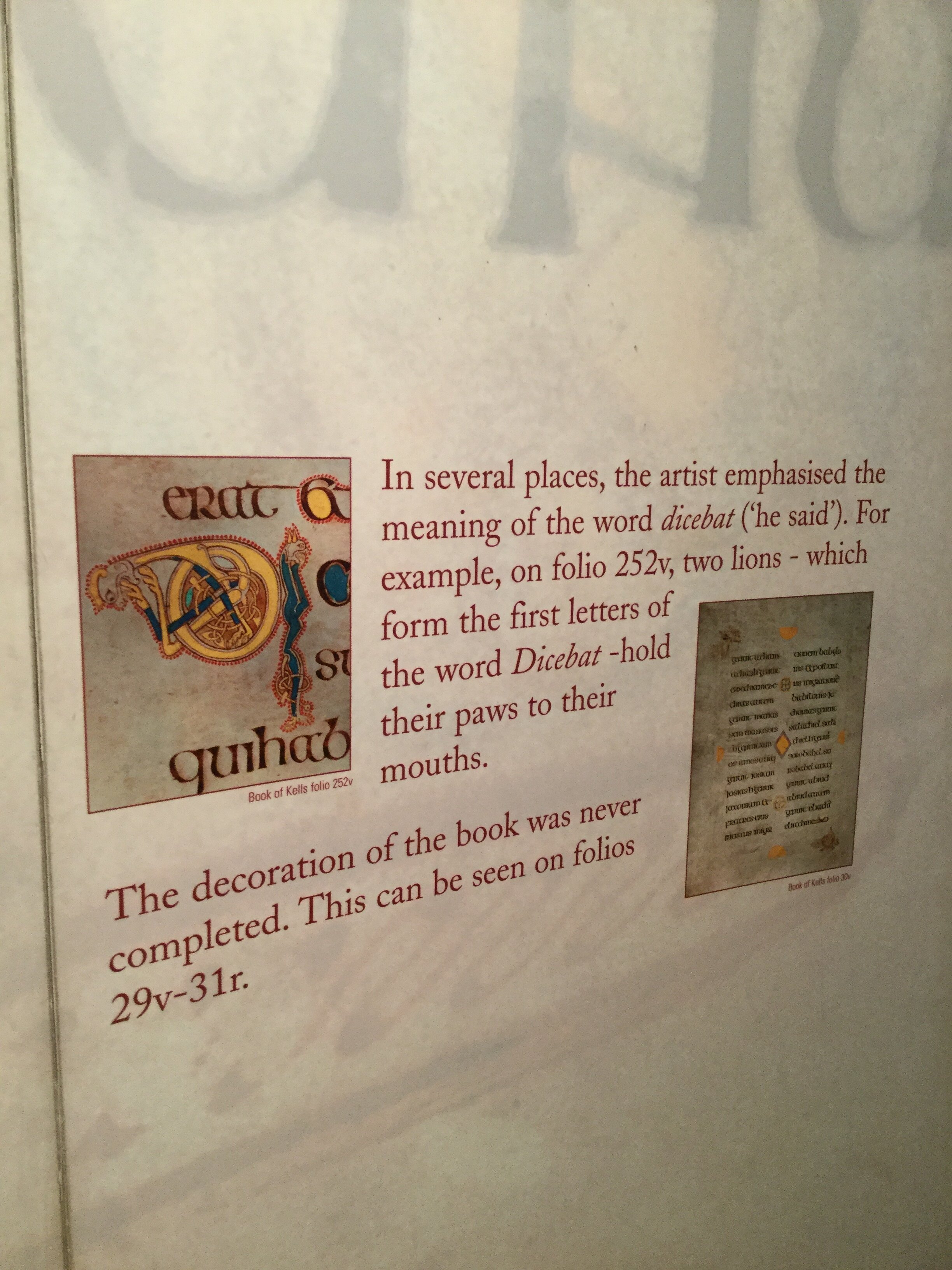

"In several places, the artist emphasised the meaning of the word dicebat ('he said'). For example, on folio 252v, two lions - which form the first letters of the word Dicebat - hold their paws to their mouths.

The decoration of the book was never completed. This can be seen on folios 29v-31r."

“The Evangelist John portrayed as a scribe: he holds a pen in his right hand, and his inkwell, made from a cow horn, is placed below his throne, above his right foot.” - The Book Of Kells Official Guide By Bernard Meehan, Thames & Hudson

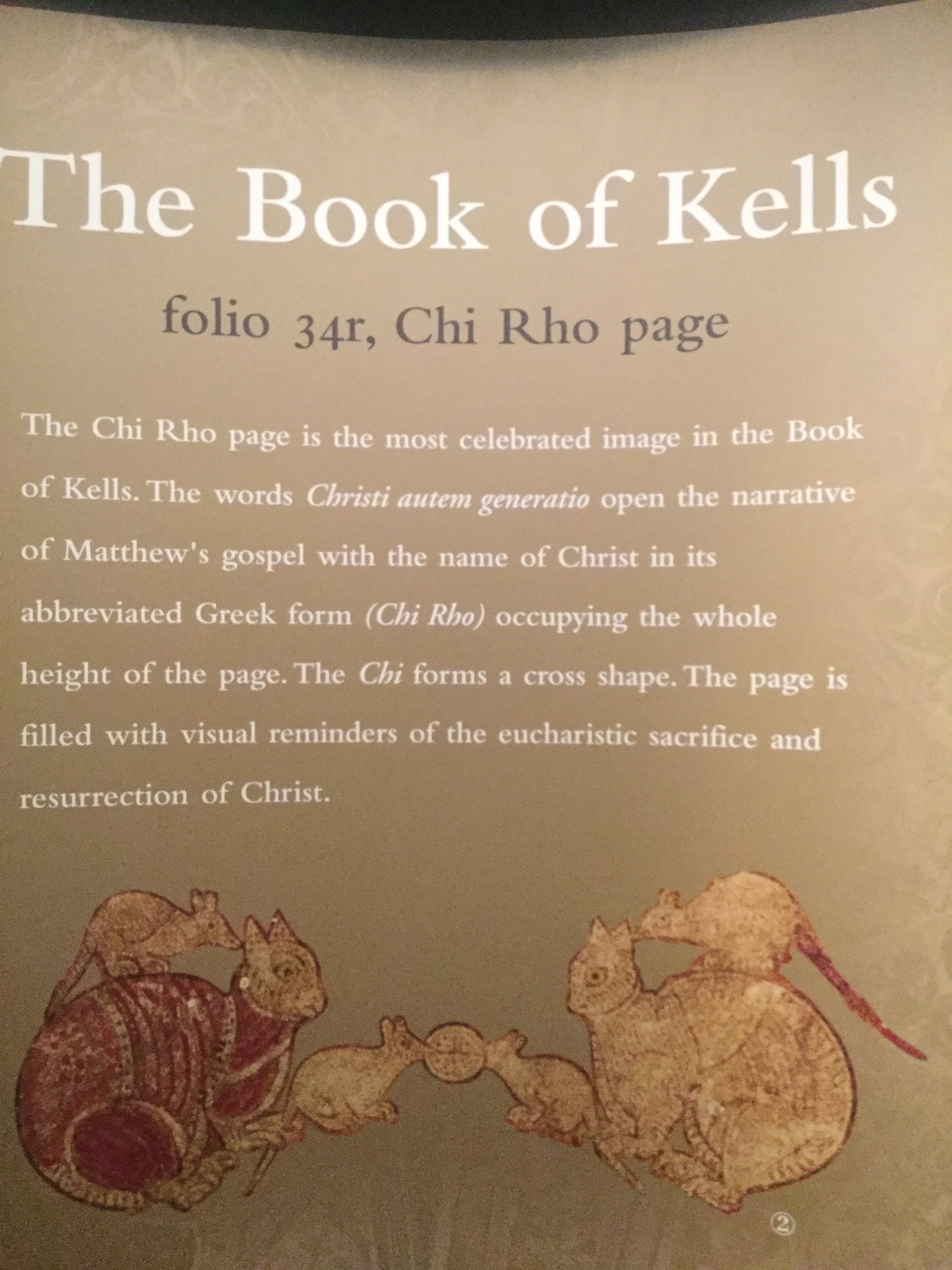

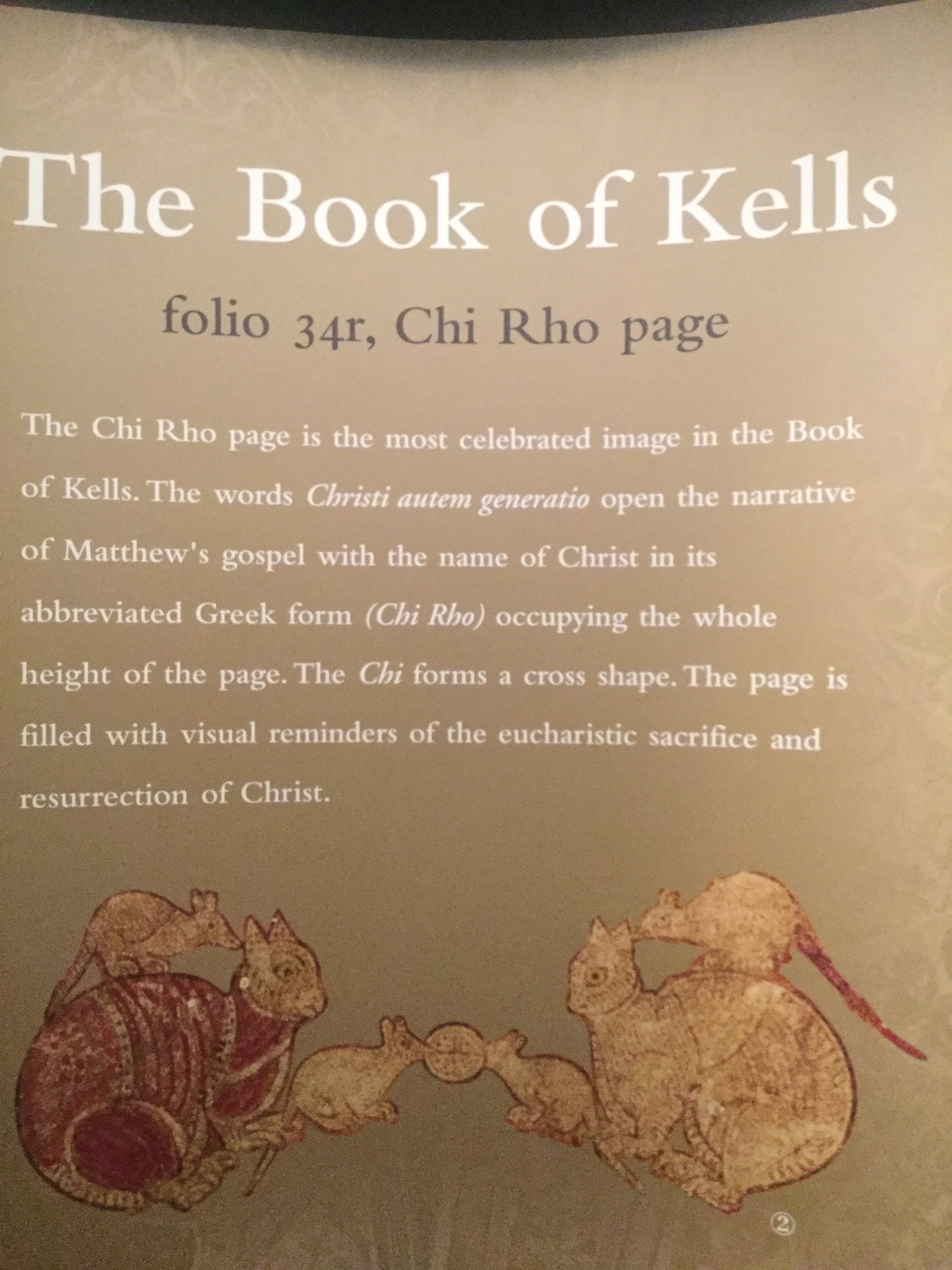

“The Book of Kells

folio 34r, Chi Rho page

The Chi Rho page is the most celebrated image in the Book of Kells. The words Christi autem generatio open the narrative of Matthew's gospel with the name of Christ in its abbreviated Greek form (Chi Rho) occupying the whole height of the page. The Chi forms a cross shape. The page is filled with visual reminders of the eucharistic sacrifice and resurrection of Christ."